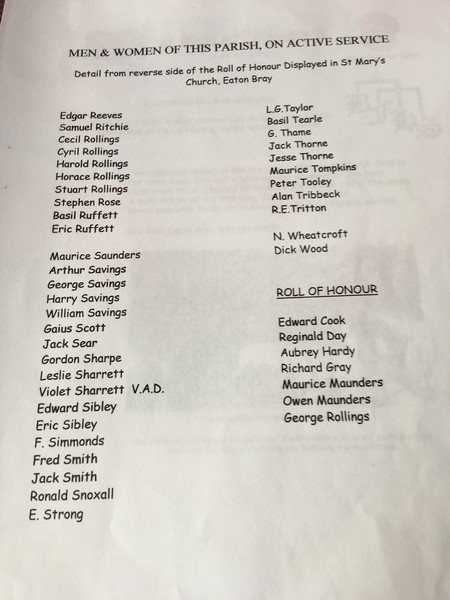

Who was the miller of Luton in the 1841 census?

Ewart F Tearle 2019

These two families have fascinated us since at least 2008, and I am aiming to lay their story out clearly, and to give my best judgement on who the families are, and why they cannot be confused. I have cleared the Tearle Tree of all references to family for both Thomas 1780 and Thomas 1777. As I research the rebuild of this part of the tree, I shall make sure that all the families are covered, and as best I can, re-filled with the genuine occupiers of their branch on the Tearle Tree.

First, I am going to catalogue all the early Thomas Tearles, any one of whom might cause a problem with us, before we research Thomas Tearle 1777 born in Cublington, and Thomas Tearle 1780, of Stanbridge. These two boys, who are first cousins, have always been the first choice of the researchers into this intriguing story. All of the boys considered below will be the grand-sons of Thomas 1709 and Mary nee Sibley.

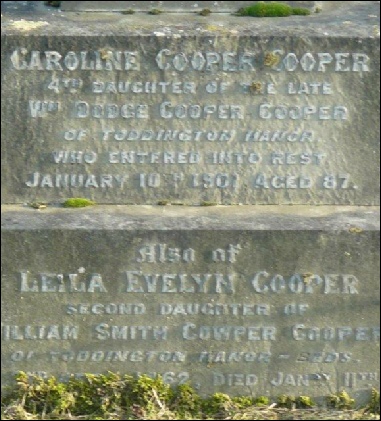

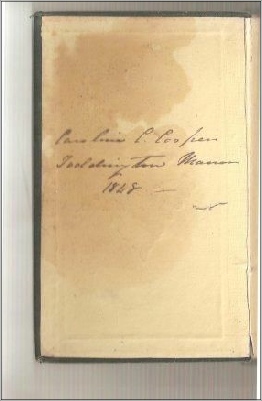

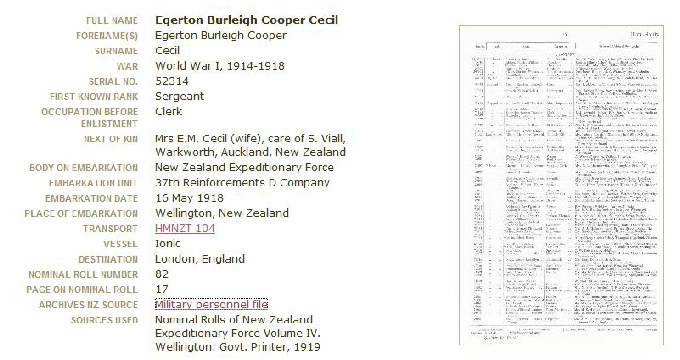

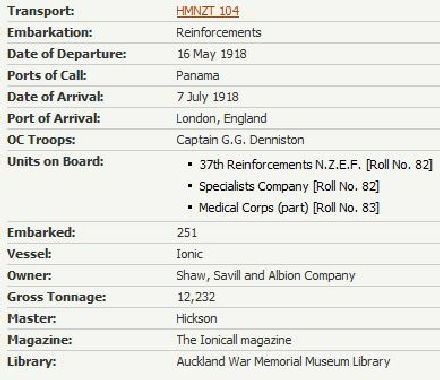

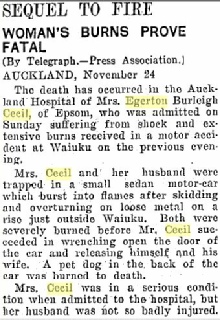

The reason we are looking at the early Thomas Tearles is because there was a Tearle family in Luton in the 1841 census headed up by Thomas Tearle, miller, aged 60. The members of his family were: Mary 60, Susan 28, Martha 25 and Caroline 20. There was also Mary Fullarton 30, Emma Fullarton 5yrs, Mary Fullarton 2yrs and Sarah Wright 30, who was a lodger. So who was this Thomas Tearle? Let’s see who might be the contender amongst the early Thomas Tearles

Joseph Tearle 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp

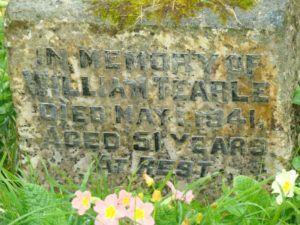

Three Thomas Tearles were born to Joseph and Phoebe – Thomas 1771, Thomas 1774 and Thomas 1780. The two earlier Thomas boys died in the same year of their birth, according to the Stanbridge PRs. Thomas 1780 married Sarah Gregory on 27 October 1802, in Chalgrave. They had a baby, Mary Tearle, baptised in Chalgrave on 14 April, 1805. In 1818 Thomas was named an executor for the will of his brother, John Tearle 1787, one of the early leaders of Methodism in Stanbridge. Thomas died and was buried in Chalgrave in 1820, just 39 years old.

Thomas Tearle 1737 and Susannah nee Attwell.

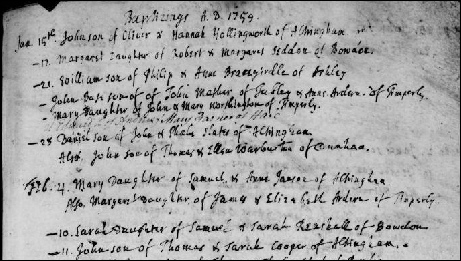

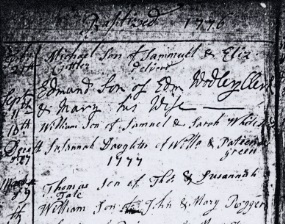

Thomas 1737 was a twin to Joseph 1737 (or they were both baptised in the same year). Thomas 1737 and Susannah are the parents of Thomas 1777 and below is Thomas’ baptism in Cublington, the first baptism of 1777.

John Tearle and Martha nee Archer

These are the parents of Thomas Tearle 1763, who married Mary Gurney. This Thomas is not a contender because the couple had their own nine children. They were married in Eaton Bray and never left it. Mary nee Gurney died in 1817 and Thomas died in 1839.

William Tearle 1749 and Mary nee Prentice

William and Mary did not name any of their children Thomas

Richard Tearle 1754 and Mary nee Webb

The last of the early Tearle boys, Richard 1754 moved to Sandridge, near St Albans in Hertfordshire, and had a son Thomas 1799. He was baptised in St Peter’s parish on 24 January 1799. That is all I know about him; I assume he died early. However, a 1799 birth date takes him out of this conversation.

So now we have the problem of two Tearle boys, separated by only three years, one whose wife has died (Thomas 1780) and one (Thomas 1777) who may never have been married at all.

I have a note from Dermot Foley in 2008:

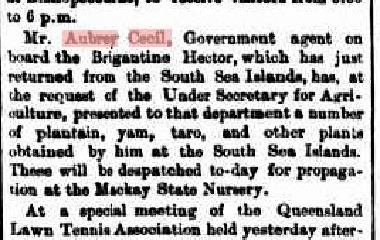

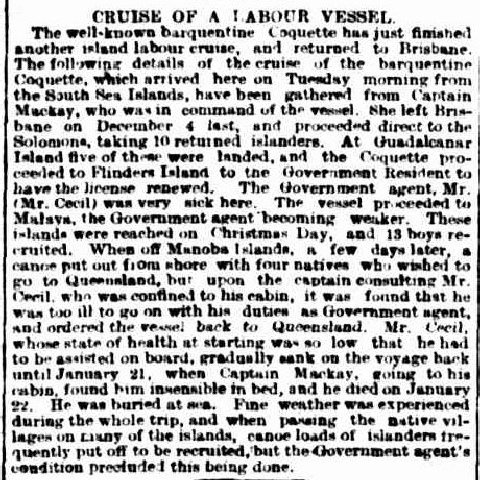

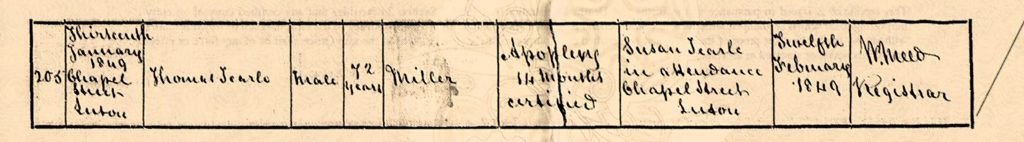

“I have been in contact with a woman who is related by blood and marriage and she insists that Thomas Tearle was the son of Thomas Tearle 1737 and not Joseph. She has seen the census return for 1841 and knows the details on the death certificate.” By this, she means that Thomas 1737, and not Thomas 1780 (son of Joseph and Phoebe) is the father of Thomas 1777, which is true, but it does not solve the problem of who is the father of the Tearle girls in Luton. The death certificate of Thomas Tearle, miller, with information supplied by his daughter Susan Tearle, is that he was 72 years old when he died in 1849. Simple arithmetic would certainly imply this is Thomas 1777. Having found out that much, let’s see if it unlocks the problem of the list of children who were in the house of Thomas the miller on the night of the 1841 census.

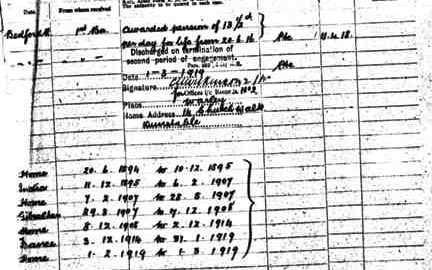

Pat sent me this from the Leighton Buzzard PRs:

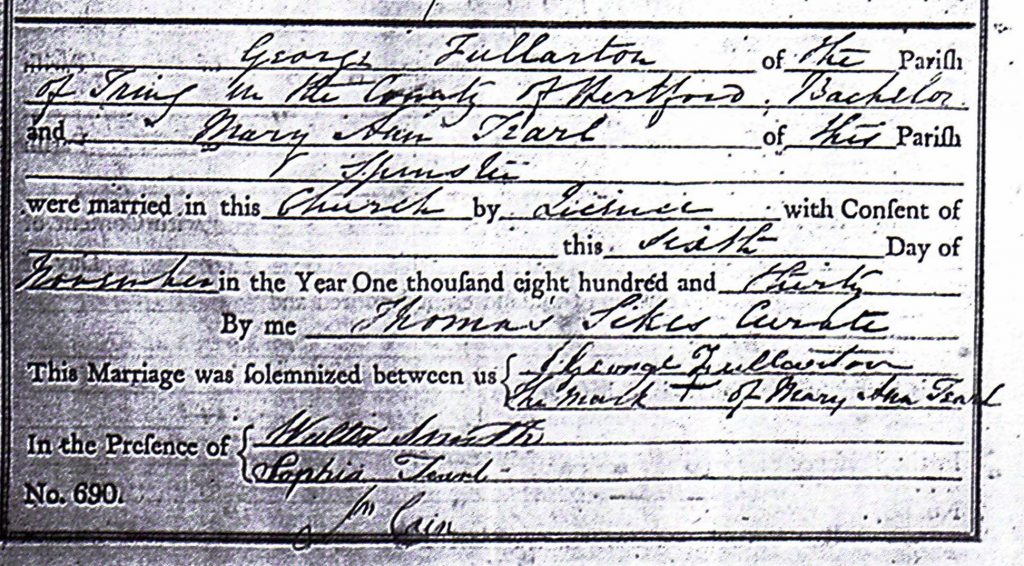

Marriage

Name: Mary Fullers

Gender: Female

Marriage Date: 21 Nov 1796

Marriage Place: Leighton Buzzard,Bedford,England

Spouse: Tho Teale

FHL Film Number: 826454, 845460

And, sadly, this may be their first-born:

Leighton Buzzard PRs, Burial:

1799 OC6 Inf of Thomas Tearle of Billington

Thomas would have been 19 when he married. I have skipped directly to Mary Tearle’s death certificate, also signed by Susan Tearle, which states that Mary was 75 at the time of her death in 1848. This would indicate she was born in 1773.

It seems unlikely that Susan would be wrong about the age of each of her parents since her father Thomas was still alive in 1848, and died the following year. If we take it that this family is one unit, then Mary Fullers married when she was 23 years old (1796) and had her last child when she was 48 (Caroline, 1821). This is possible today, but I do not know about the circumstances in Victorian times. However, in a 2008 essay, in my notes on the Tearle/Fullarton families I was at a loss as to how Thomas 1780 marries Mary Fullarton and has a large family from 1802 to 1821, remembering that this same Mary will still be 48 when she has her last baby, no matter who she marries. Also, it is not possible for Thomas 1780 to have any more children after 1820. Consider also that Thomas 1780 cannot be confused with Thomas 1777, because Thomas 1780 was a dealer in straw plait in 1818 in the Chalgrave area, whilst Thomas 1777 was a journeyman miller in Luton. There are also the local boundaries, such that Thomas 1780 and his family were centred on Chalgrave, whilst Thomas 1777 lived in Houghton Regis and moved south on the A5, through Dunstable, to live in Luton. Again, Thomas 1780 has one wife, one child, and died aged 39 whilst Thomas 1777 lives in Luton, he is a miller and he has a wife and five daughters and dies at age 72. This is Pat’s way of differentiating the two families, and I think she is right. Pat’s killer blow; “I do not think this is the same Thomas, they are two different people.”

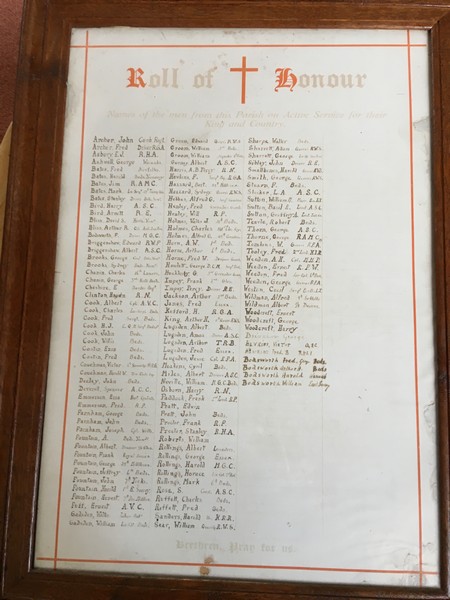

Having put the challengers behind us, let’s have a look at the fascinating story that is exposed by the documentation, mostly the changes wrought by advancing technology, and the totally different lives that Bedfordshire women could afford themselves because the straw hat industry allowed them to work when, where and how they wanted. The shining example of the miller’s family is that they are all women, and only one becomes married. I think that speaks volumes about Victorian women and the grinding, care-centric male-dominated society in which they lived, along with the daily tragedy of young women dying in childbirth. If you can avoid marriage – do so.

I should also note that my term for Thomas – the miller of Luton – is not to imply that he owned a mill. Sometimes he called himself a miller, and at other times he called himself a journeyman miller.

The 1841 census in Luton lists the following people living in the house of Thomas the miller:

- Thomas Tearle 60yr

- Mary Tearle 60yr

- Susan Tearle 28y

- Martha Tearle 26y

- Caroline Tearle 20y

- Mary Fullarton 30y

- Emma Fullarton 5y

- Mary Fullarton 2y

- Sarah Wright 30y

We can see in the list above that there is another Fullarton, also called Mary. She is the daughter of Mary Tearle 60y, who has married George Fullarton in the Church of St Mary, Luton. Emma and Mary Fullarton are her children.

Also in the 1841 Luton census, we find Sophia Tale (Tearle) living with Ruth Field in Castle Street. Both are straw hat workers. Sophia is aged 30, which would make her born in 1811, and therefore younger than Mary (1805) and the same age as Susan, but census ages are not always particularly reliable with this small item of data. Ruth Field and Sophia are living next door to a house occupied by John Field.

1851 census: Neither Thomas nor Mary are alive for the 1851 census, but many of the people in the 1841 census are still living together, this time in Chapel St, Luton:

- Susan 38y

- Martha 35y

- Caroline 34y

1861 census: the house looks very much like the 1841 census, except the members in the house are in 31 Wellington St, Luton. This was a long lane of shops, on both sides of the street, with accommodation above. The Tearles lived here for at least 40 years.

- Susan 48y

- Martha 46y

- Caroline 44y

- Mary A Fullarton, niece 22y

Mary Ann Fullarton married Edward Bachini, an Italian from the city of Florence. They were married on 10 October, 1862, in Luton. I have listed four of their children on the Tearle tree, and Mary Ann died in 1924.

1871 census: Here is much the same group living in the house at 170 Wellington St, Luton:

- Susan 58y

- Martha 48y

- Caroline 46

- Ellen Hoy, niece 14y

You will see Ellen Hoy 1857, in at least the next four censuses, because her mother, Emma Fullarton 1838, married Charles Hoy in Luton, 1855. It is unclear why and how Charles went to Luton from Enfield, London, but Ellen Louisa Hoy was their only child. Emma died in 1856, probably caused by childbirth. Charles married Ellen Elizabeth Irons from Wheathampstead, near St Albans, in 1857, and I have documented all of their children up to the 1881 census.

1881 census: 170 Wellington St, Luton

- Sophia 76y

- Susan 67y

- Martha 62

- Caroline 60

- Sarah Cadwell, lodger

- Ellen Louise Hoy 24y

And on the same page as above:

- Charles Hoy 48y

- Ellen Elizabeth Hoy 43y

- Kate Hoy 22y

- Harry Hoy 16y

- Alfred Ernest Hoy 11y

- Frank Horatio Hoy 9y

- Charles Hoy 6y

The 1881 census is the third time we see Sophia. This time we know she is the eldest sibling, because she is the head of the house. Ellen Louise Hoy stays with the Tearles while Charles Hoy and Ellen Elizabeth cope with their growing family.

1891 census: 194 Wellington St, Luton

- Susan 78y

- Ellen Hoy 34y

- Mary Fullarton nee Tearle 81y

- Emma Hoy 18y

1901 census: 194 Wellington St, Luton

- Mary Fullarton nee Tearle 93y

- Ellen Hoy 47

- Sarah Cadwell, boarder

Now that we have the facts before us, we can look at the relationships of the people in this story. There is some conjecture that the first two girls (Sophia and Mary) might be half-sisters, or cousins of the rest of the girls, because Mary Tearle and Sophia fit nicely into the early year gaps, and therefore might be the girls from the marriage of Thomas 1780 and Sarah nee Gregory. However, Mary Fullarton nee Tearle says she was born in Thorn (a satellite of Houghton Regis https://www.houghtonregis.org.uk/the-history-of-houghton-regis ) so it is not close enough to Chalgrave, and since everyone else is associated with Houghton Regis, then so is Mary, and so is Sophia. I have Mary’s marriage certificate of 6 November 1830. I have no idea why she should say she was Mary Ann, nor why George Fullarton should sign himself J George Fullarton. But the fact is, Mary Tearle is the bride, and Sophia, her sister, who has signed as a witness, has attended to ensure things go well. As you can tell from the censuses above, these two women are the sisters of Susan, Martha and Caroline Tearle; five girls, all sisters, and Thomas 1777, miller of Luton and Mary nee Fuller/s his wife, are indisputably their parents.

This investigation could stop here, but I think a few words of follow-up would not go amiss. Let’s tidy up some loose ends.

Who was Mary Fuller and where did she come from? She was called Mary Fullers in the Leighton Buzzard PRs, but I think that’s incorrect. I have found a 1773 baptism for Mary Fuller in Millbrook, Bedfordshire. Her parents on that document are Richard Fuller and Sarah Crawley and they were married in Millbrook, in 1773.

Here is the data from Ancestry:

- Name: Mary Fuller

- Gender: Female

- Baptism date: 20 Dec 1773

- Baptism place: Millbrook, Bedfordshire, England

- Father: Richard Fuller

- Mother: Sarah

- FHL Film Number: 599351

How did they end up in Luton? I know that the march from Millbrook to Luton might give cause for some to think that I am stretching things a little, but the 19th century was a time of vast change, especially for rural farming families. If a Tearle family from Leighton Buzzard can leave the town and trek all the way up to Preston, and never come back, it’s not difficult to visualise a rural family leaving Millbrook for a better life in Luton.

The Mary Fullarton 30y in the 1841 census was Mary Tearle, who married George Fullarton. Now, who was he? Barbara Tearle assures me that the post-war parish registers published by the Bedfordshire Record Office have Fuller and Fullers, but no Fullartons. The reason is that the Fullartons were a Scottish family from Castle Douglas in Kirkcudbridgeshire. George Fullarton was in Castle Douglas for the 1841 census. We now know that George’s parents were Henry Fullarton and Mary Anderson, both born in Kirkcudbridgeshire. Also in the 1841 census (this time, in Luton) are Mary Fullarton 30y, Emma 5y and Mary 2y, George Fullarton’s family at that date. We find out in the 1861 census that Mary Fullarton, niece 22y, the daughter of Mary and George Fullarton, is actually Mary Ann Fullarton. She is the niece of all the Tearle women in the house.

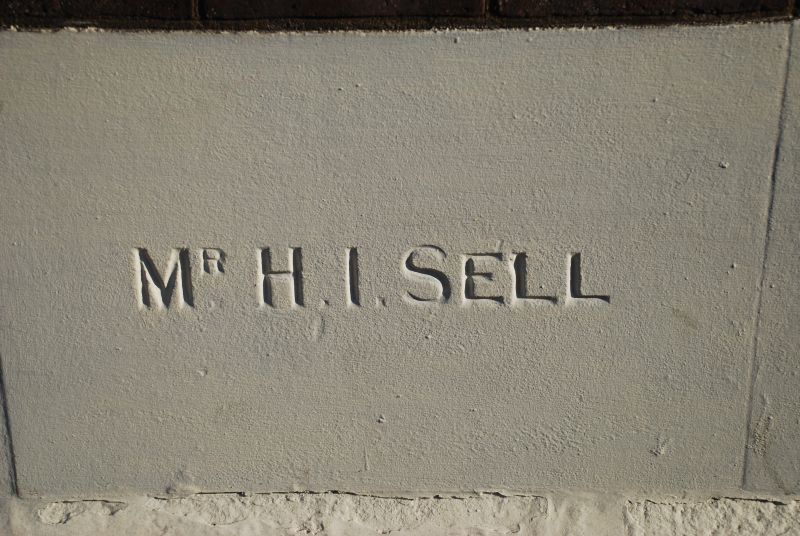

George and Mary Fullarton nee Tearle had three girls; Emma Fullarton 1838, Mary Ann Fullarton 1839 and Eliza Fullarton 1849, who married Henry Isaac Sell in 1888. As far as I know, Eliza and Henry had one child, Lillian Sell, in 1896. Harry Isaac Sell was significant enough in his church to have a plaque which memorialised him. That church has become the Luton Christian Fellowship church in Castle St, and Harry’s plaque is still there.

Another incident that has clouded the picture somewhat, and that should also be cleared up is the question of Charles Hoy and Ellen Elizabeth Irons. Emma Fullarton 1838 married Charles Hoy in Luton, 1855. She had just one child, Emma Louisa Hoy in Luton, 1856. It would appear she died as a result of that birth in about July 1856. Charles Hoy then married Ellen Elizabeth Irons, in 1857.

Emma Louisa Hoy stayed with the Tearle women: she is with them for the 1871, 1881 and the 1891 censuses. She had her own baby on 16 Oct 1872 and called her Emma Hoy. Emma married William Robert Betts in Luton in mid 1899. I know of one child, Marjory Emmie Ireal Betts, born 6 April 1909 in Luton. She married Stanley J Prince in Colchester, January 1946, and died in Colchester in 1997.

I think I have covered this story as deeply as it can be, in that I wanted to chart the early years of the Tearle/Fullar/Fullartons to resolve the question of which Thomas was the miller of Luton, and parent of the very independent Tearle family who lived there. A question that was answered by Pat as early as 2008, but which has worried me considerably over the years since then, is now put to rest.

My heartfelt thanks to Barbara Tearle, to Pat to Richard Tearle and to Dermot Foley, for not giving up on this story.

were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”

were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”