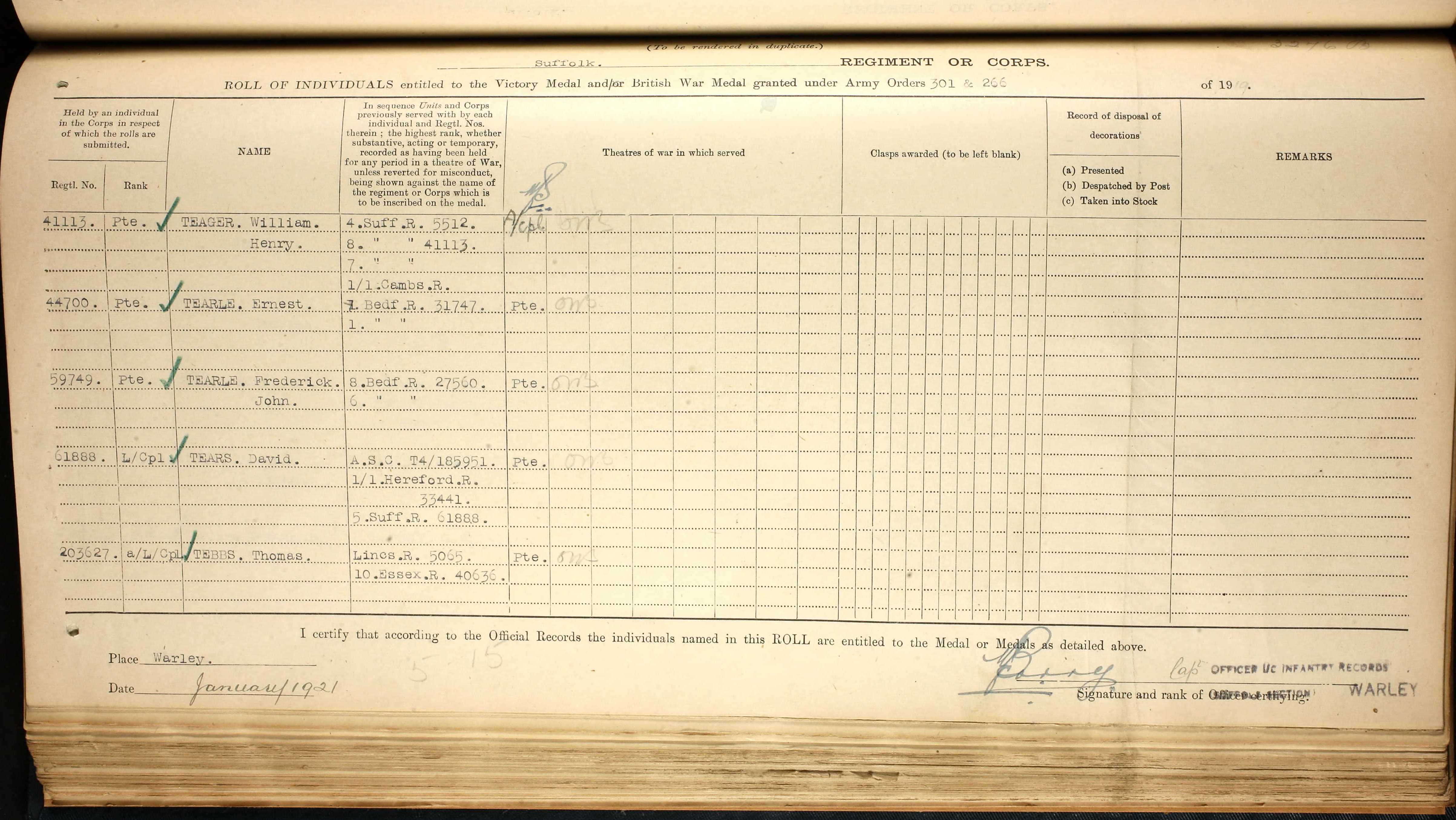

It was Richard Tearle, leader of the Tearle research group, who first came across the story of William Tearle, the Cornish firefighter. He wrote to me in January, 2009.

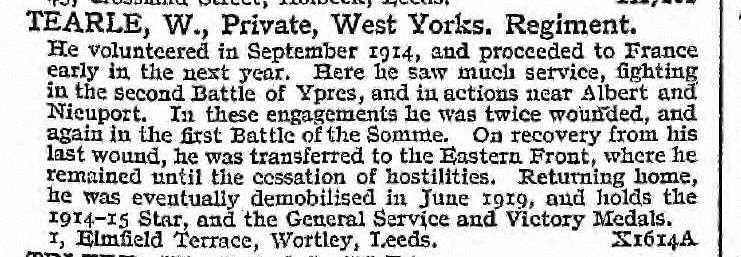

Ewart – whilst idly browsing, I came upon this article:

“In September 1939 the National Fire Service was formed with Lostwithiel being a part of the service. By this time, `Loveday’ was replaced by a trailer and drawn by a lorry that was kept in Skelton’s Garage, Bridgend. Lostwithiel was frequently called to attend fires in Plymouth, Devonport, and Torpoint during the blitz of 1940 – 1941. During one of these raids, Section Leader Tearle lost his life, he was one of Lostwithiel Unit’s earliest casualties of the war.”

There are no other details that I can find – do we have any records of Tearles in Cornwall? This man clearly died as a civilian, albeit a member of the fire brigade. ‘Loveday’, by the way was a horse drawn steam engine….

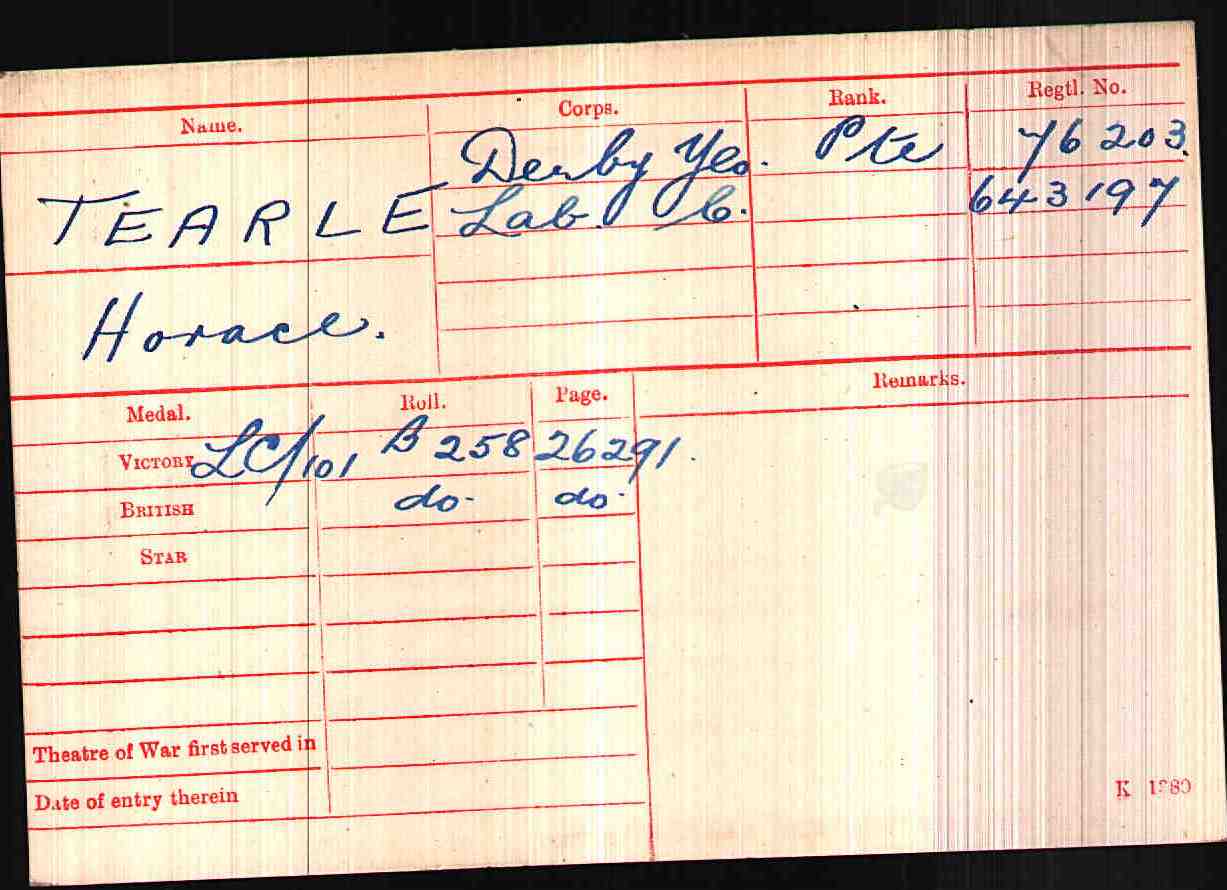

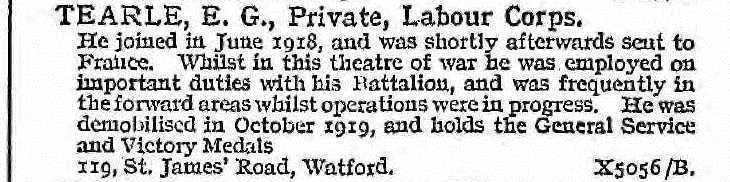

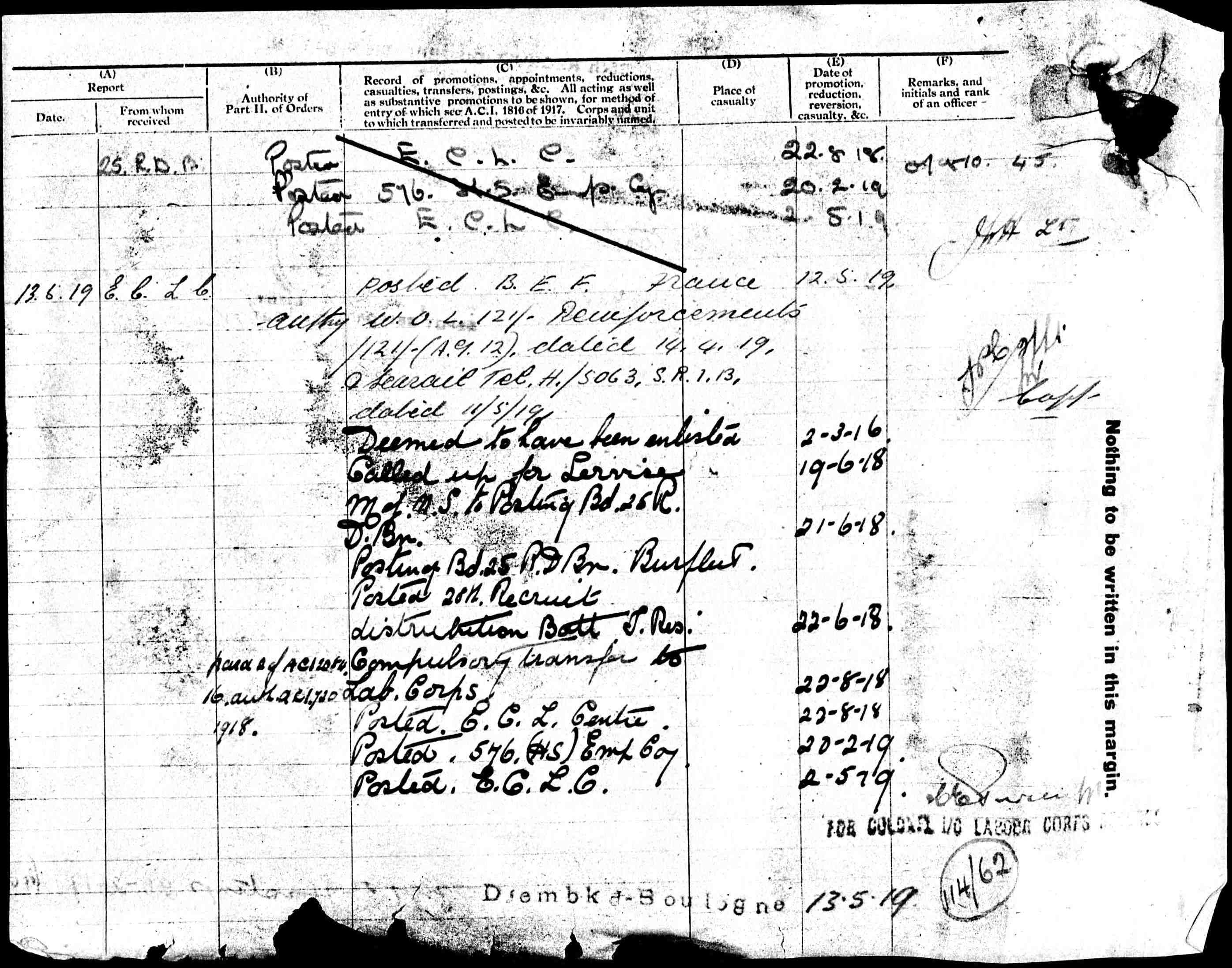

Tracy Stanton was quickly onto the story – she had found the death registration: Q2 1941 William A J Tearle Bodmin reg dist. vol 5c page 234. Age 51.

And she had found more –

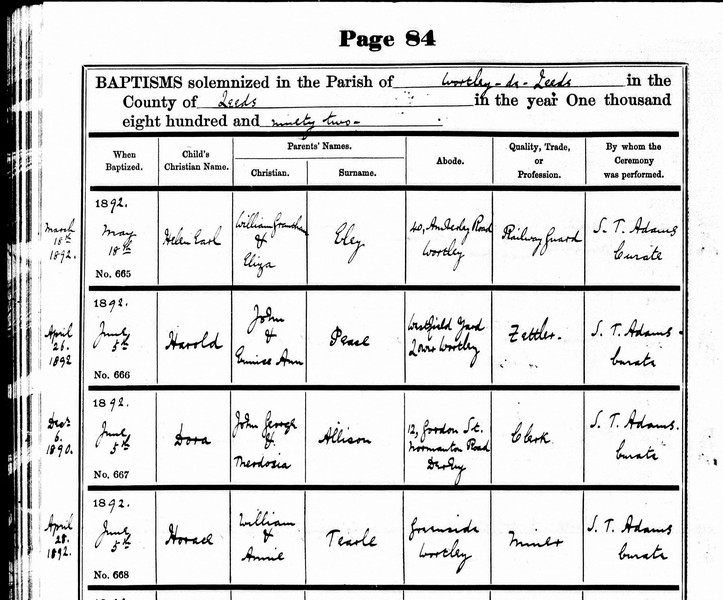

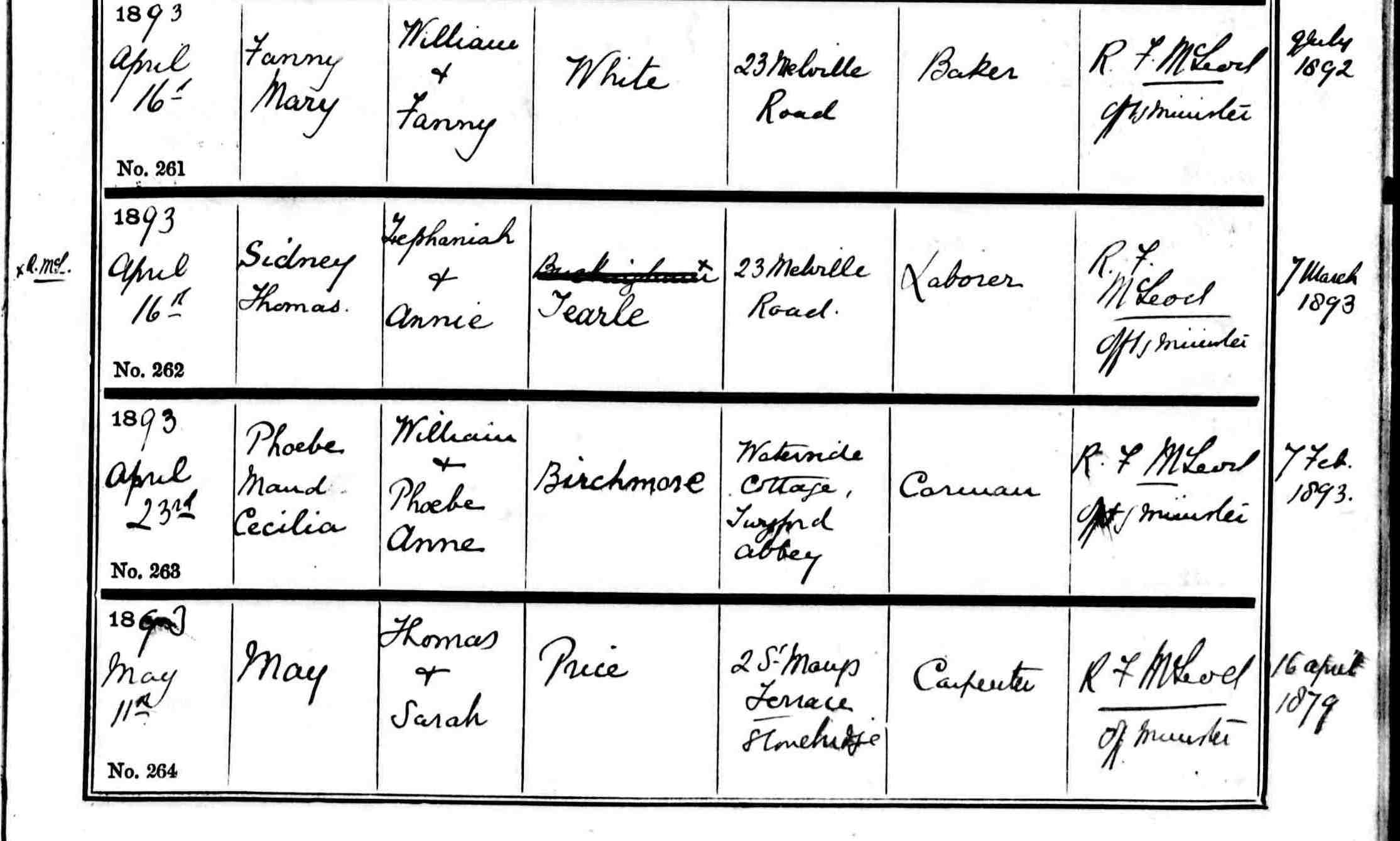

“On the Firefighters Memorial site the date is given as 26 April 1941 but his MI in Restormal Rd Cem. reads as 1 May 1941. He appears to be William Alfred J Tearle born 1890 Woburn district. I found him in the 1891 census in Toddington, mother Eliza. Ann born Falmouth, Cornwall.”

Pat Field added to the growing list of telling details:

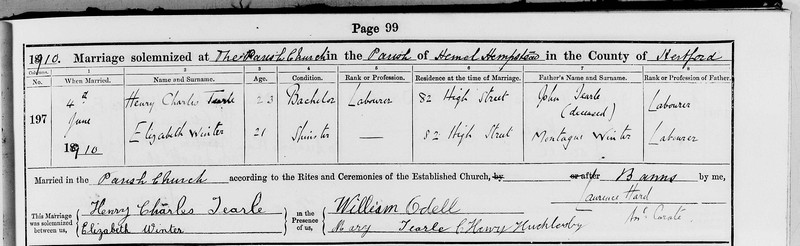

“Could this be a grandson of John 1831 and Maria Major? They had a son William 1863 born in Toddington.

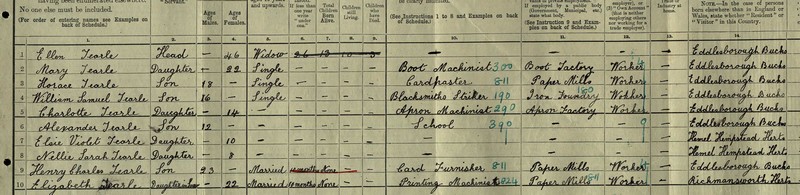

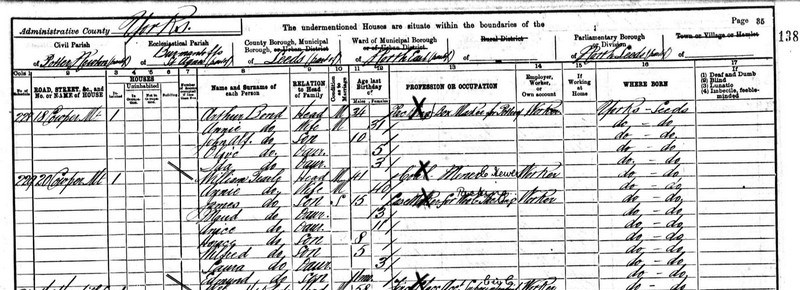

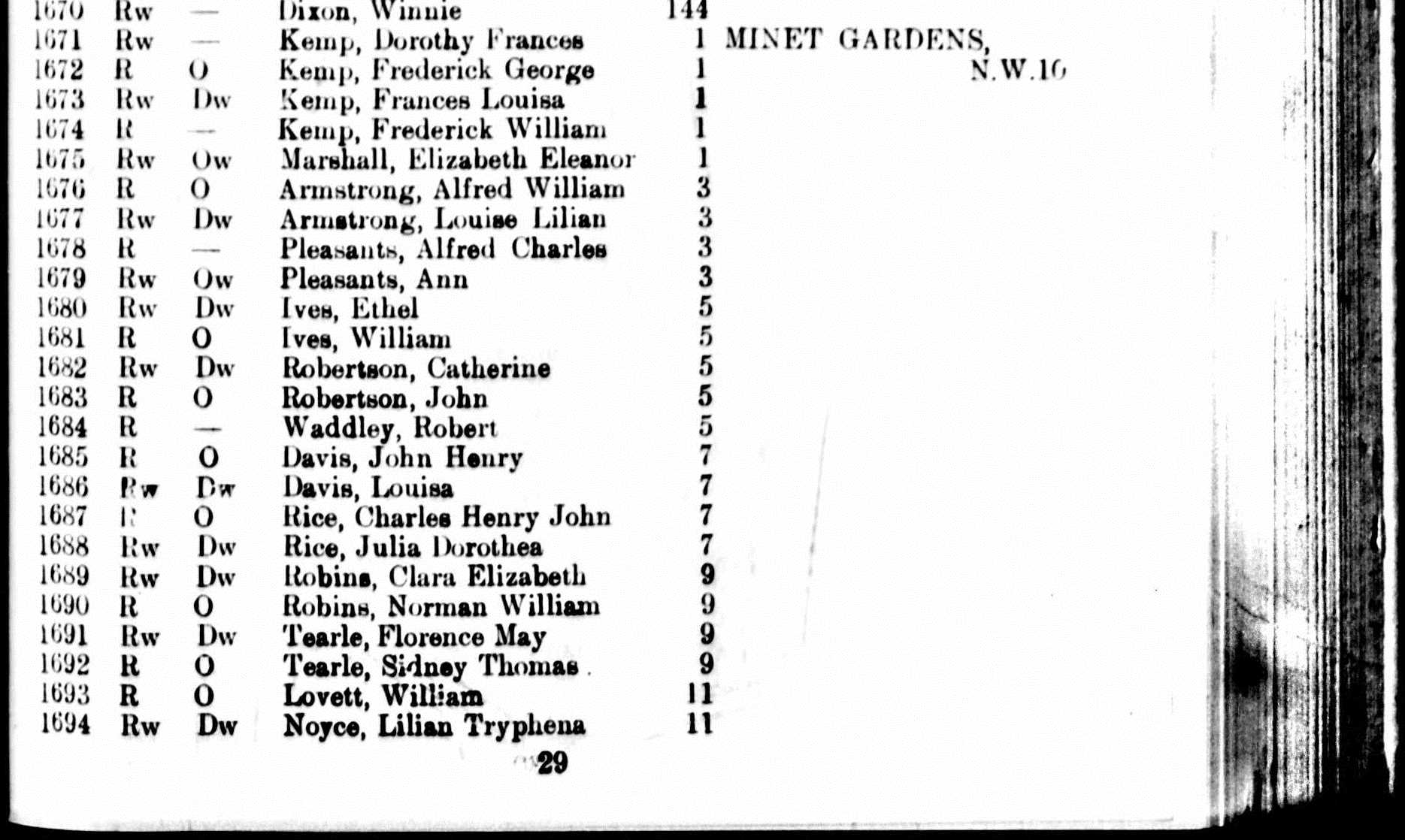

1901 census: 7 Albany Road Toddington gives us William Tearle (transcribed Searle) 37 Carter born Toddington, Elizabeth 38 Wife born Falmouth and children Elizabeth 19 born Acton, Violet 15 born Acton and William A J 11 born Toddington.”

We had found a Toddington man who had moved to London, married a Falmouth girl, had three children in London, moved back to Toddington and had one more. That lad, William, had moved to Lostwithiel, Cornwall, and died fighting fires in the Plymouth Blitz. Extraordinary. If he was 11 in 1901, then he was a perfect age to be dragged into WW1, which he obviously survived.

I found the Lostwithiel Museum and rang the curator, Tremar Menendez. I asked him if he knew of a William Tearle. “Oh,” he said, “You best talk to Gillian Parsons, she knows everyone and everything.”

Smiling, I rang the number he gave me. Gill Parsons did know everything. She and a fellow museum committee member had researched William and his death and had written an article for the Museum Monthly. She would send it to me. As a result of the article, the Firefighters Memorial Trust had carried out its own research and agreed that William’s name should be added to the Firefighters National Memorial at the head of the Millennium Bridge, close to St Pauls.

“I have seen that memorial many times and examined it closely twice. I have not seen a Tearle name on it.”

“His name,” she said, “was added in November 2008.” I had not been to see the monument since about August.

Her article, a letter and some photographs arrived by post a couple of days later. She had met Victor, William’s son, in the village – he had just been to London to see the monument and he was very pleased. “Apparently,” she wrote, “his father married Ellen Hambly from Covich’s Mill (a very small hamlet about three miles away) near Lostwithiel.” William’s name had been added to a memorial in St Andrews Church, Plymouth, and Victor remembered going to the ceremony many decades ago. Victor would be pleased to speak with me if I contacted him.

Unfortunately, Victor could hardly understand a word I said because he was very deaf. “Is it all right if I come and see you?” I asked. “I would like that,” he said.

“How would you like to go to Plymouth for a week in the holidays?” I asked Elaine.

“The furthest west we have been is Ilfracombe, so that would be good,” she said. “What’s the occasion?”

I told her my plan was to see the memorial in St Andrews Church in Plymouth and then go to Lostwithiel to meet Victor.

“Lost who?”

“Lost-with-ee-yall. Brunel country,” I said. “There is a fabulous bridge near Plymouth, a railway station in the village, and a Roman bridge.”

St Andrews Church, Plymouth.

St Andrews Church was in the very centre of Plymouth and overlooked a bombed-out church lower down the same hill. The firefighters memorial was a brass plaque mounted on the wall in a small chapel. It was deeply moving. Every man listed had died fighting fires in Area 19 (Plymouth) during WW2. Tearle, W. A. J. was clearly visible at the bottom left.

St Andrews Church was in the very centre of Plymouth and overlooked a bombed-out church lower down the same hill. The firefighters memorial was a brass plaque mounted on the wall in a small chapel. It was deeply moving. Every man listed had died fighting fires in Area 19 (Plymouth) during WW2. Tearle, W. A. J. was clearly visible at the bottom left.

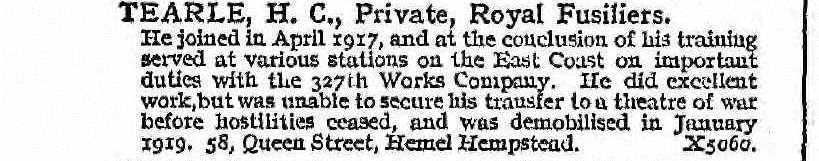

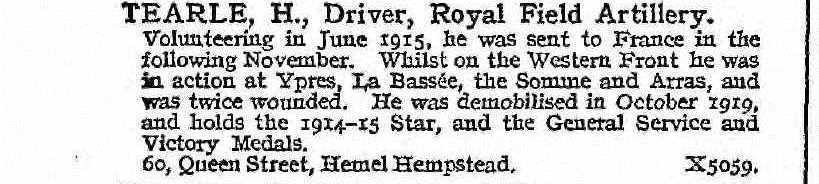

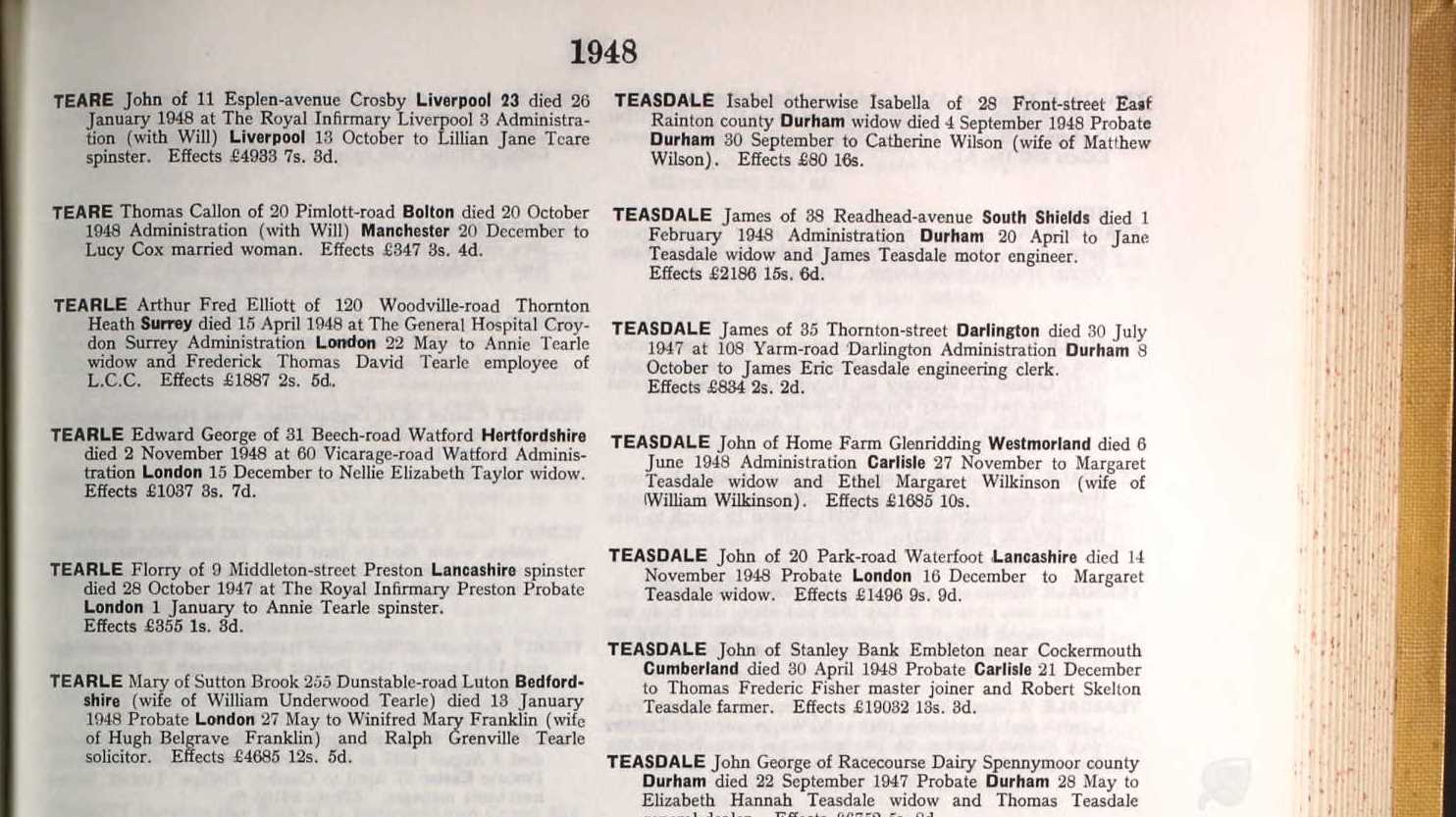

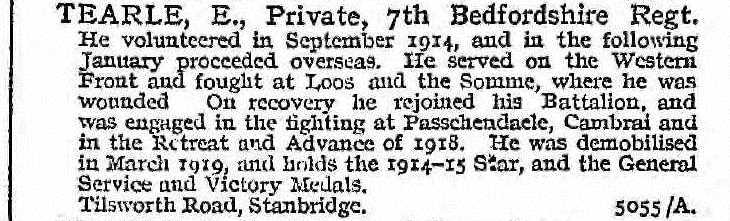

The outside of the chapel was lined with several small cabinets containing large books of people’s names; victims of both wars.Two of the volumes were of National Roll of the Great War. I asked a churchwarden if I could see the contents and he gleefully brought me the key. The books were beautifully printed on stiff, cloth paper, but there were no Tearles in them. Another cabinet had a hand written volume of remembrance for the Merchant Marine. I looked for Louisa nee Lees, but again, there were no Tearles. We spent the rest of the afternoon on Plymouth Hoe, examining all the monuments on Monument Hill, including those of the Crimean War and the Boer War. The Plymouth Naval Memorial took the longest, because out of sight of this view, below, is another huge semi-circle of names. There were no Tearles.

Plymouth Naval Memorial

The following morning we arrived in Lostwithiel; it was a voyage of about 20 miles and the roads that William had traveled to fight fires in Plymouth would not have been as good as the one we had driven on. How did he manage it? It was raining heavily. We met Gillian Parsons. “I’ll show you around the village and then I’ll take you to meet Victor. First, though, is the museum.” We walked down an alley near the river. “This is the Fowey River,” she nodded towards the building on the other side, “and the big building is Brunel’s warehouse. The other buildings were part of the railway station, but have been converted to apartments. Brunel’s building is untouched.”

“The railway?” I asked.

Lostwithiel Museum

“We are on the line from Paddington to Penzance via Plymouth,” she said. “It wasn’t dug up by Dr Beeching so it still works.” She stopped. “Here is Fore St. It used to be called High St, but not now. Mind you, it still is the high street.” She unlocked the door of the museum. “I’m afraid you can’t take any photos,” she said, “but this is the very first Lostwithiel fire engine, given to us in 1716 by Lord Edgcumbe. Alongside it are the bellows from the smithy.”

I looked at the tangle of wooden spars and wheels. It was like something out of a storybook that had suddenly come to life. The fire appliance was tiny, and obviously horse-drawn. How on earth did it ever put out fires? There was no tank; where did the water go? “It delivered men to the fire, not water,” she said. “When they got there, they fought the fire with buckets and beaters.”

“When I first heard about the Lostwithiel Fire Service,” I said, “they mentioned a horse-drawn fire appliance called the Loveday. Is this it?”

“No,” she said. “That was the third appliance the service owned. It was bought in 1904 and was definitely our most famous. The Loveday was named after her daughter by the then mayoress of Lostwithiel and this building was the old fire station that the Loveday set out from for any of the village fires. The new fire appliance was a trailer pump unit, drawn by a lorry, which was garaged in Bridgend. It’s only just up the hill so the men did not have far to go to get it.” She opened a drawer and showed me a remarkable photograph.

William Tearle 1890 right rear with the Lostwithiel Fire Service team.

“Here is the Loveday,” she said, “a steam-powered, horse-drawn pump. By late 1939, shortly after this photo was taken, the National Fire Service was formed and we took delivery of our new appliance.”

I studied the picture with William, marked with a cross, sitting proudly at the front of his beloved fire engine. “The Loveday was a Merryweather appliance, quite well known in London, where they also had self-propelled versions. Ours may have been horse-drawn, but it still put out fires and it still saved lives,” said Gill.

“What happened to it?”

“Victor said it has ended up in a museum in America,” she said a little wanly. “It’s sad that the local people did not value their treasures years ago. The new fire station is at the entrance to the town car park, it’s called B17. We had to campaign for years to get it. We are a volunteer service now, but we used to run a Green Goddess.” She waved her arm around the interior of the building. “Did you know this used to be the Corn Exchange?”

“I suppose there wasn’t a lot of corn to sell,” I said, taking in the size of the room. I am used to the St Albans building. In both cases, the telephone rendered the building superfluous to requirements.

“Upstairs was the Guildhall and it is still the council chambers.”

“The council meets upstairs?”

“It has for hundreds of years.” I looked at the squat, round form of the bellows with its long handle folded back over the top. It was a little like a small, over-fat barrel, and was possibly made of leather with a wooden plate on the top. I didn’t dare touch it. “The smithy was used until quite recently,” said Gill, “and it was sold when the last blacksmith died. Actually, I’m not sure you’d call him a blacksmith; he made wrought iron art objects rather than shoeing horses.” She smiled, “Would you like to see it?”

On the corner of North St and Church Lane stood this unprepossessing, square three-storeyed building and next to it was a much older slate-roofed squat building with a big bay window.

“The smithy is a seventeenth-century building and you can see its double doors, including this half-door. The last blacksmith made the sign above the door.”

I looked closely at the sign “LOSTWL SMITHY” and the vents in the roof. “It’s a private dwelling,” she continued, “and not connected to the house any more, but that’s where your William worked, and the house on the corner was where he and Ellen and their children lived.”

I looked closely at the sign “LOSTWL SMITHY” and the vents in the roof. “It’s a private dwelling,” she continued, “and not connected to the house any more, but that’s where your William worked, and the house on the corner was where he and Ellen and their children lived.”

She produced another picture. “Here’s a photo Victor loaned me which shows William at the smithy.” I looked at the picture and the building in front of me. I could see the opening to the forge, now covered by a bay window, and I could see the main door fastened back against the left-hand wall, with the business sign just visible above it. “There was more than one smithy in Lostwithiel,” she said, “but this used to be quite a hub of village life. William was close to the high street and used to make horseshoes in a variety of sizes and hang them in the smithy ready for use. If someone turned up unexpectedly, William could always find shoes to fit. He gave a very good service, too. When he shod a horse he cleaned each foot, trimmed it and polished it so that the owner, when he paid, felt he had received a lot for the price he paid. In winter, William had one of the few warm places in town, so that anyone with time on his hands, and a word to spare, would drop in on the smithy and have a nice conversation, while he warmed up with his back to the forge!”

“How much did he charge?”

“For shoeing horses? In the 1930s I should think around three shillings per horse.” I thought about it. “In 1960, my dad said to me it would make all the difference to him if he was earning five pounds a week. So seven horses a day would be a guinea and six days a week would be six guineas. He’d have to line them up, wouldn’t he?”

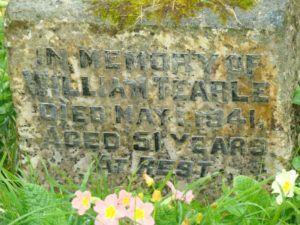

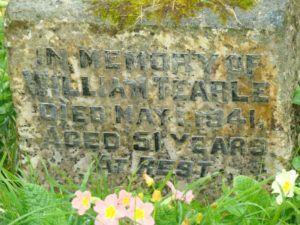

Gill smiled, “Would you like to see the cemetery now?”  We opened the gate to the Restormal Rd Cemetery and secured the lock. “I have catalogued all the headstones in the cemetery, so I really do know everyone here,” said Gill. “The churchyard was closed a long time ago and for a while this was a kind of churchyard extension, kept tidy by the sexton. These days, it is owned by the council, and they maintain it.” She led us down a cleanly mown strip of grass, slippery in the wet. “There is the headstone,” she said. “It has been moved for some renovations to the cemetery, so I am not sure where the grave actually is.” I cleaned the headstone the better to read the inscription.

We opened the gate to the Restormal Rd Cemetery and secured the lock. “I have catalogued all the headstones in the cemetery, so I really do know everyone here,” said Gill. “The churchyard was closed a long time ago and for a while this was a kind of churchyard extension, kept tidy by the sexton. These days, it is owned by the council, and they maintain it.” She led us down a cleanly mown strip of grass, slippery in the wet. “There is the headstone,” she said. “It has been moved for some renovations to the cemetery, so I am not sure where the grave actually is.” I cleaned the headstone the better to read the inscription.

“That’s lead lettering in Lostwithiel granite,” said Gill.

“That’s lead lettering in Lostwithiel granite,” said Gill.

I stood up and took a pace back to see the headstone sitting in the grass, glistening in the rain and surrounded by dancing spring flowers. Each of us stood for a moment, reading the inscription and thinking of what had brought us together in this place and at this time. “I’ll take you to see Victor now,” said Gill. “I promised Mavis we’d be there by 1pm.”

It wasn’t far from the Restormal Rd Cemetery to Victor’s and from their cheery wave we could see we were well received. Gill, pictured on the right with Elaine, introduced us to Victor and Mavis and left.

“What a lovely lady,” said Elaine. “The museum is lucky to have her; she went so far out of her way to help us today.”

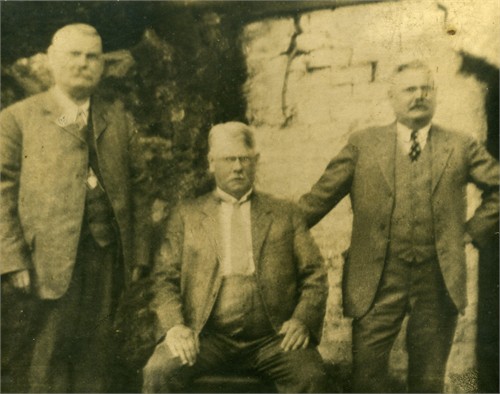

Mavis had put lunch on the table for us and while we ate Victor showed us the relics his father had left behind, and told us the story of his life. “Here’s a picture of the family,” he said.

He carefully lifted a small sepia print from the mantelpiece and pried off the back of the frame, the better for me to see it.

“He was born and bred in Brentford, London,” he said, “and he had two sisters; Myrtle and Olive. That’s Myrtle standing on the left, then me, Victor Raymond Hambly Tearle sitting on my mother’s knee. Her name is Ellen Rosina nee Hambly. Standing in the middle is my brother Frederick Hambly Tearle, then my father William Alfred John Tearle, then Olive.” He looked up.

“But there’s one missing – ten years after this photo, my mother had a younger brother for everyone, whom she called William. He was a quantity surveyor and yard foreman for Churchill and Johnson, a building firm in Basildon. He went there to live with Myrtle and Olive. He was killed in a lorry accident near Luton and he is buried in the Leyndon cemetery near Basildon.” He looked at me carefully. “He was only 7yrs old when Bill (my father, William; they always called him Bill) was killed.” He continued, “Myrtle was born in 1916 and she married Donald Jones in 1939. Now, Olive was born in 1920 and she married Alf Mitchell. Fred, he married Evelyn and I was born in 1925 and I married Joan Goodman in,” he thought for a moment, “1947/48/49. She died of breast cancer when she was only 34yrs.” He looked intently at the photo as if to drag from it some insight into these family tragedies. He scanned the photo and his eyes stopped on the picture of his gently smiling father.

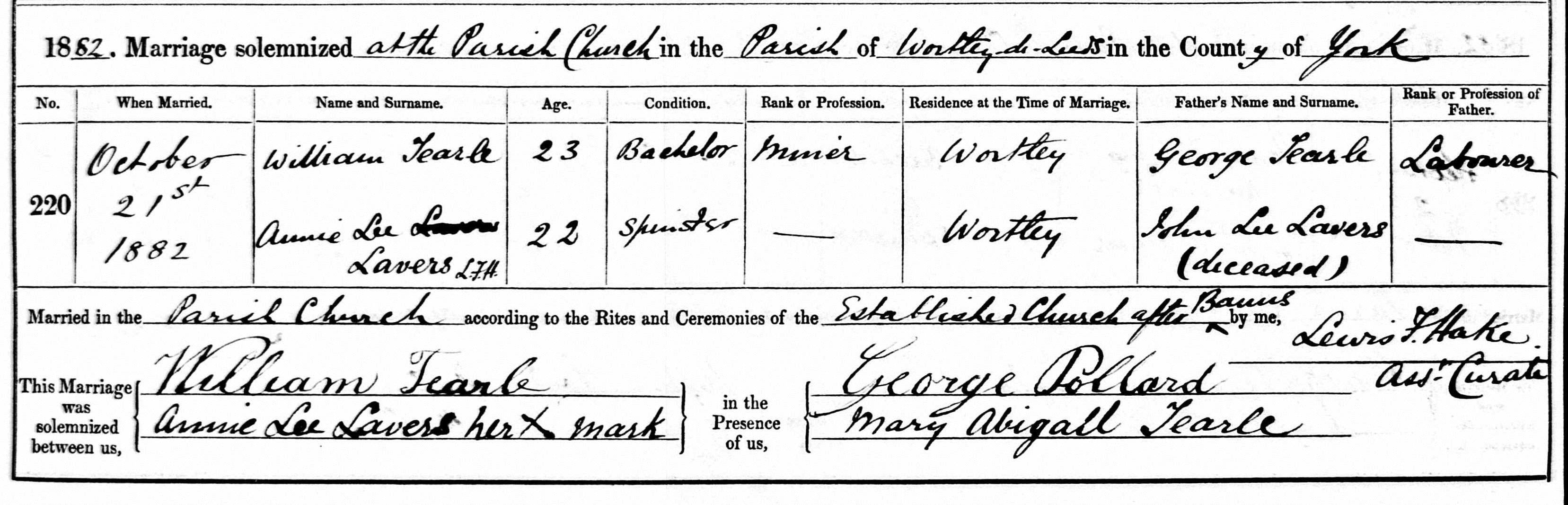

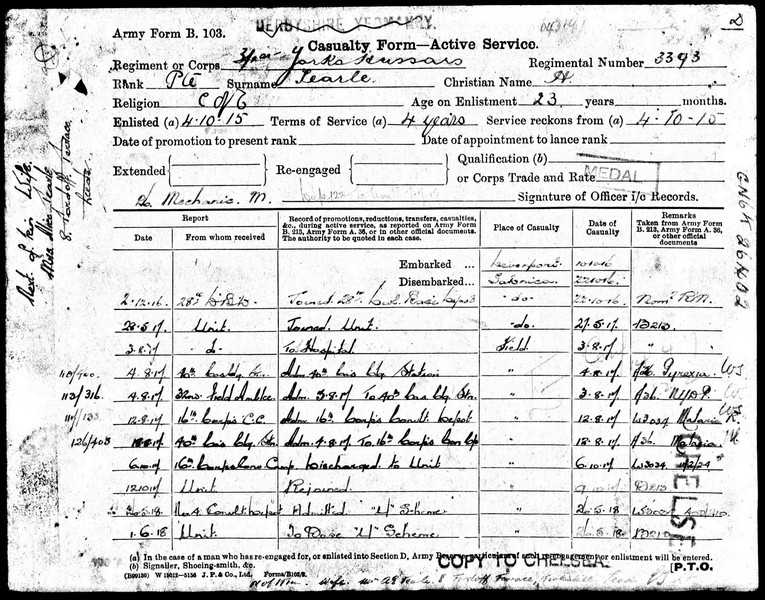

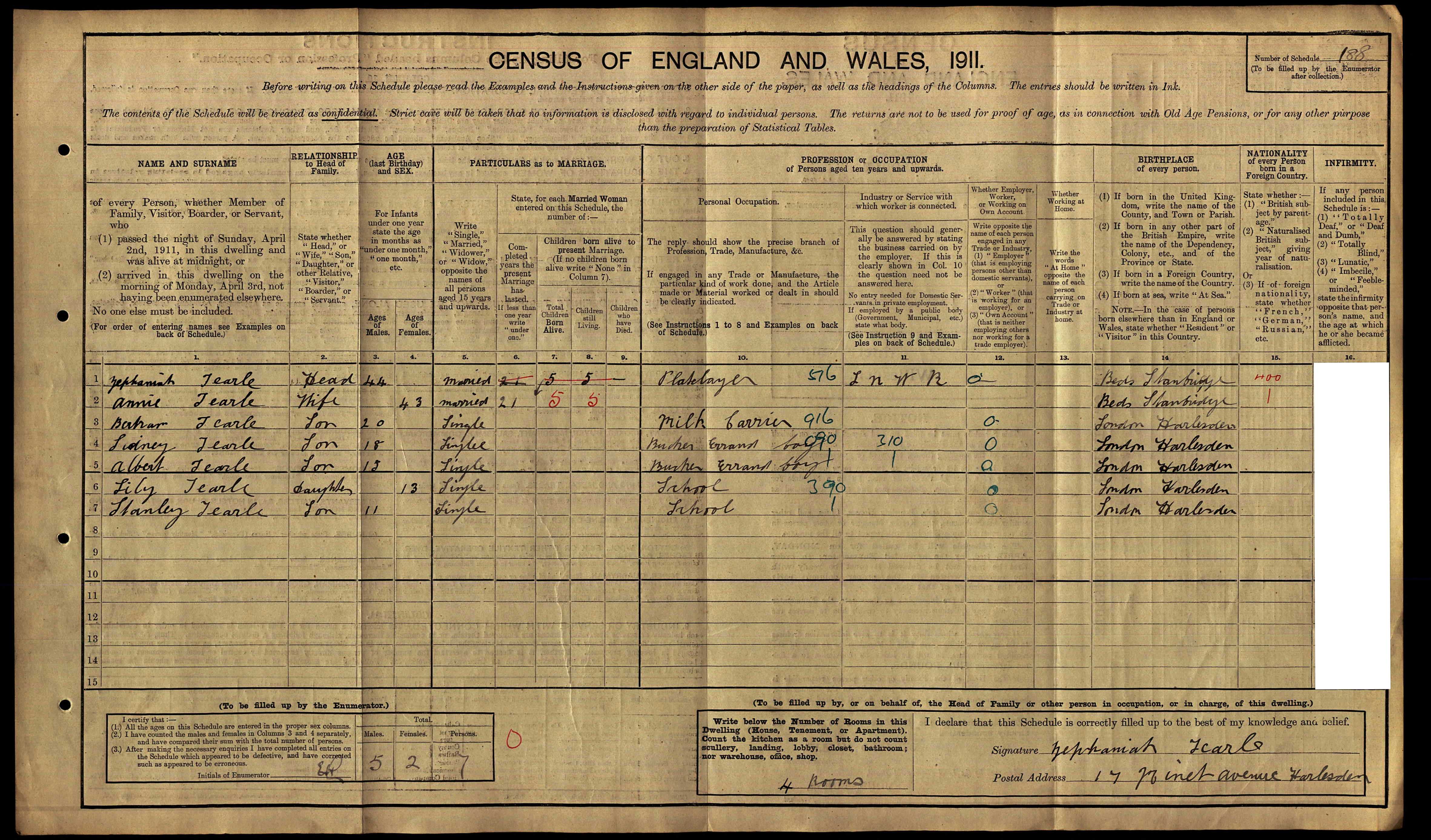

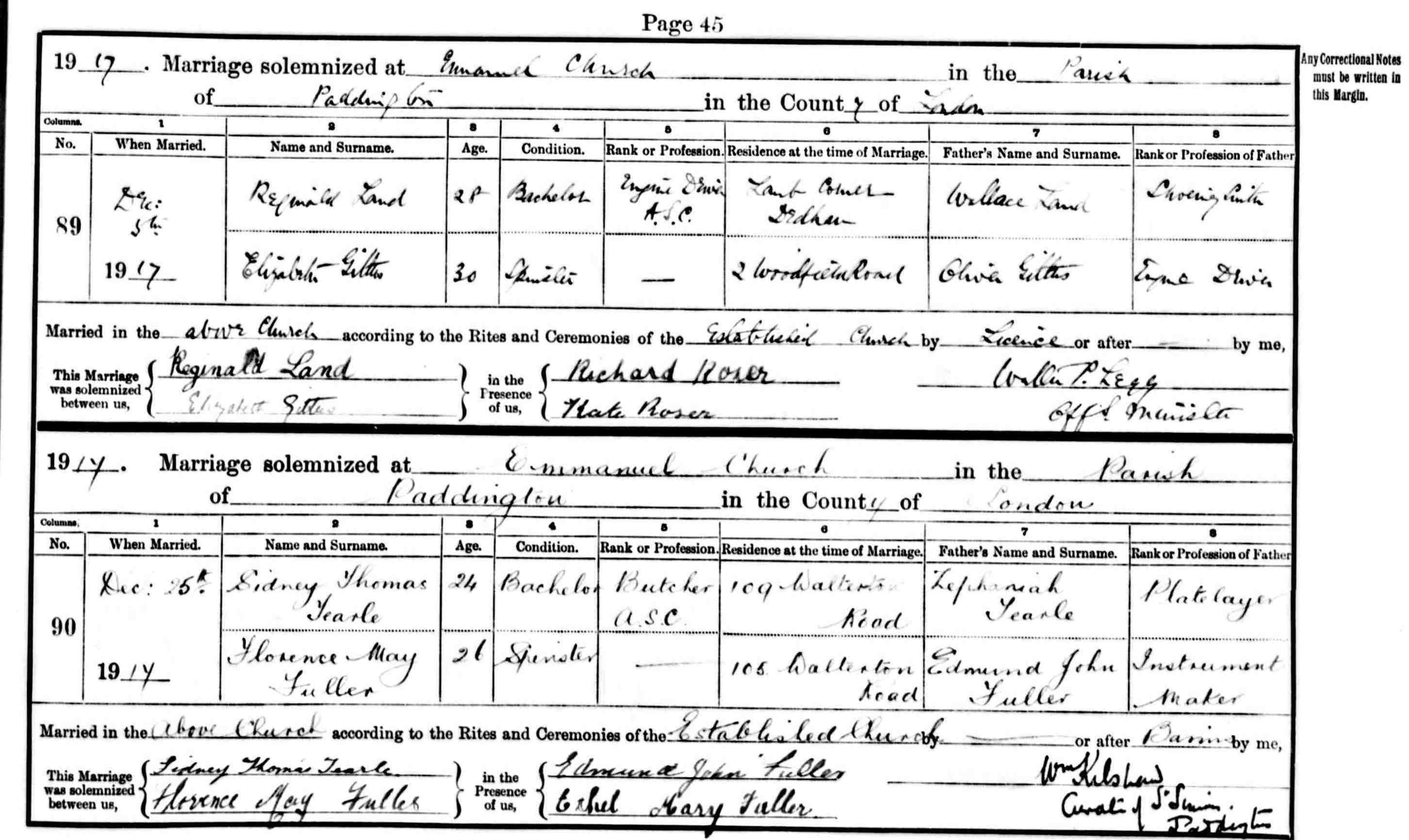

“He became a blacksmith in Brentford, and he joined the Royal Horse Artillery to fight in the Great War. They sent him to Cornwall and he was carting gunpowder from Trago Mills. That’s how he met my mother. They married after the war in Braddock Church and they lived in Taphouse, then in Sandylake Cottage just out of Liskeard, then they came to Lostwithiel and moved into the house on the corner of Church Lane. My father set up the smithy in that little building alongside the house. It had five bedrooms, so when my grandparents came to live with us, it was a good thing the house was a big one. My grandfather, William, was an employee of the Greater London Council. My father wanted me to become a blacksmith like him, but I joined Coop and Brewers the local bakers, who were also my father’s best customers. I took an apprenticeship with George Brewer.”

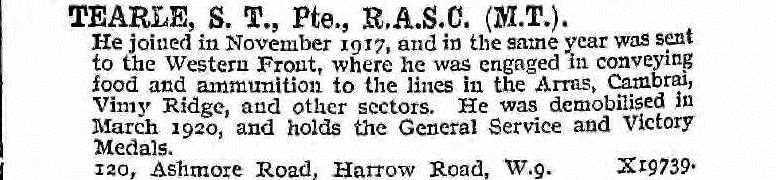

“My father worked with the Loveday, you know,” he said. “He joined the Lostwithiel Fire Brigade in the 1920s and it may be in a museum now, but he fought fires with it. In those days, the brigade was owned by the council, and they supplied the uniforms, but the men had to buy their own trousers. That museum you went to was the Fire Brigade building. In 1939 the Loveday was retired and there was a new fire pump, which was mounted on a trailer and drawn by a lorry. That was the time when the National Fire Service was formed and my father became Section Leader Tearle. They would call him the Station Manager now. During the Plymouth Blitz, the men worked during the day, then they’d get the call at night to fight fires in Plymouth. He would take the fire engine to Saltash – you’ve seen the Brunel Bridge?”

I nodded.

“It’s a railway bridge, no way across for a vehicle. So they loaded the fire unit – lorry and trailer – on to the ferry and crossed the river that way. In those days the ferry was drawn across the river by chain. My father was in command of the fire brigade and he would work all night long and then come home, and have to work all day in the smithy as well.”

He had come to the hard part. He put down the picture. “The lorry had the ladders on it and the trailer with the pump got pulled along behind. The men sat up on the lorry amongst the ladders. The lorry fell into a bomb crater and my father was thrown out onto the road, with the ladders falling on top of him. He was taken to Bodmin hospital and died there 4 days later. Peritonitis.”

“Let me show you what kind of son he was.”

Victor opened the glass door in the cabinet behind me and brought out two small objects, a cutlass and an anvil. “Bill brought home the knife and the anvil from Calais after WW1. They

Victor opened the glass door in the cabinet behind me and brought out two small objects, a cutlass and an anvil. “Bill brought home the knife and the anvil from Calais after WW1. They  were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”

were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”

I tried to distract him, “What did you do in the war?”

“I joined the Royal Navy as a baker on the HMS Onslow. Fred joined the navy, too, as a petty officer shipwright. One of my best friends, also a baker’s mate, was on the HMS Exeter. He died when she was torpedoed. My first wife, Joan, was a WREN.”

“I saw the Exeter on the Plymouth Naval Memorial, I said. “Your friend’s name would be there.”

“The Onslow was Cap’n Dee’s destroyer,” said Victor, resuming, “and it was sold to the Pakistan government after the war, to help form the Pakistan Navy. She was torpedoed, too, when I was working on her, but the torpedo didn’t explode. Do you know what that’s like?” He pointed to his left, “The officers’ quarters are aft,” he waved to his right, “and the rest of the crew is for’ard, but the kitchens are amidships. That means we sit above the magazine. When you are torpedoed in the magazine there is a hell of a big bang.

We heard the torpedo hit, then later we heard it explode, but out to sea on the other side of the ship. I can’t tell you how relieved we were. We worked the North Atlantic route guarding convoys taking supplies to the Russians from Scapa Flow. I have a service medal given to me by the Russians but I wasn’t allowed to wear it until quite recently because of the Cold War.

After the war, we were part of the escort that took the King of Norway back to Oslo. We were met by a fleet of little boats, some of which had been three days at sea, waiting for us.”

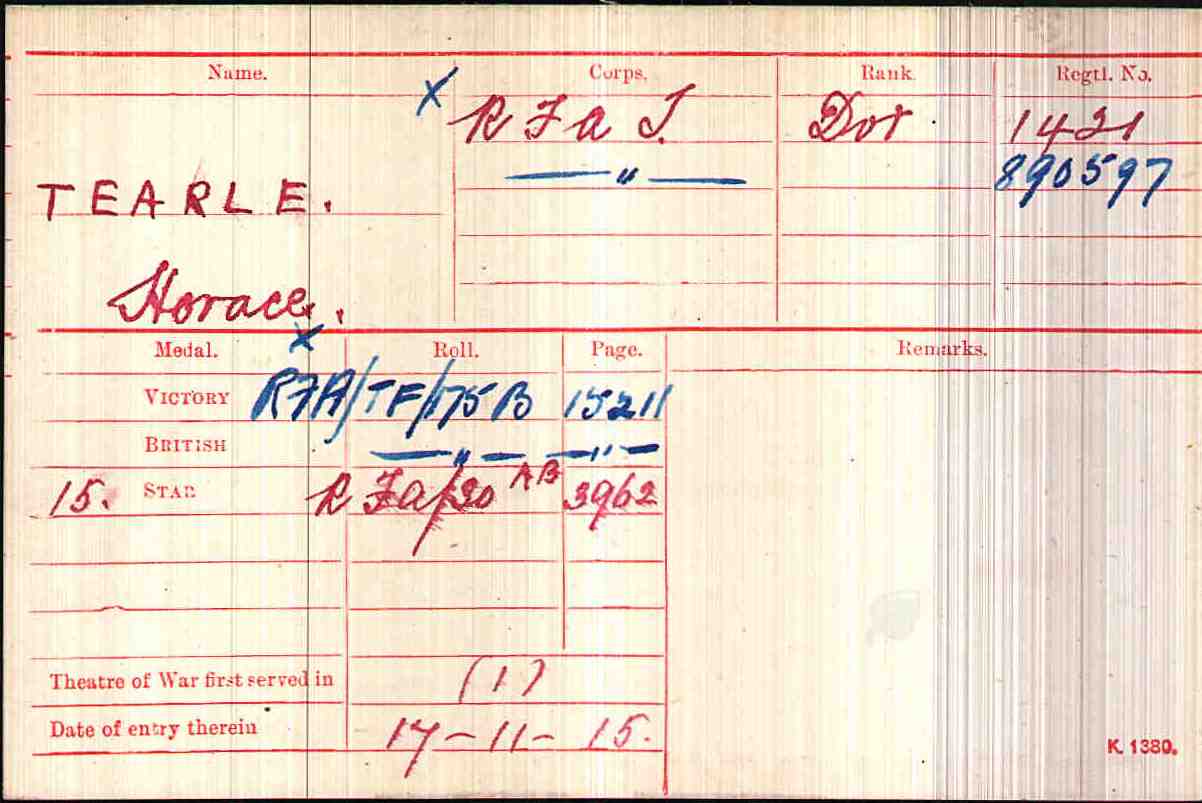

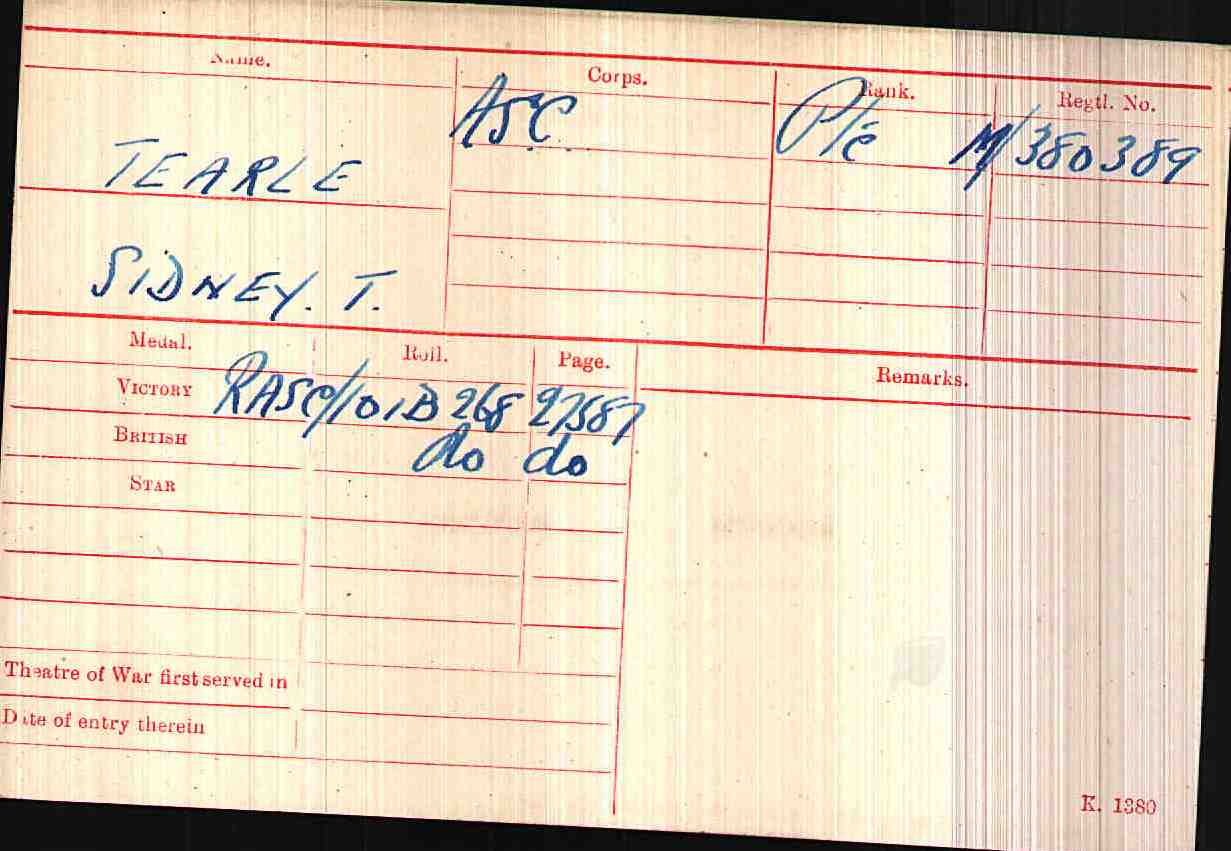

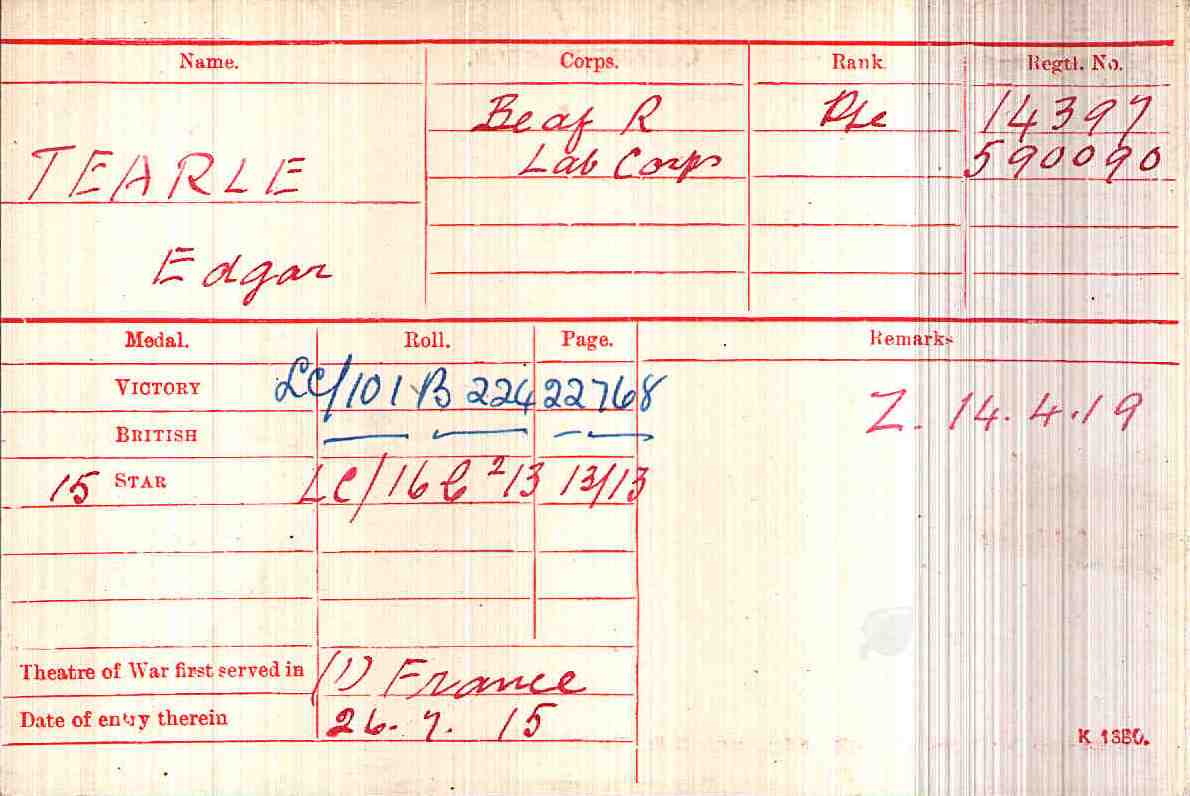

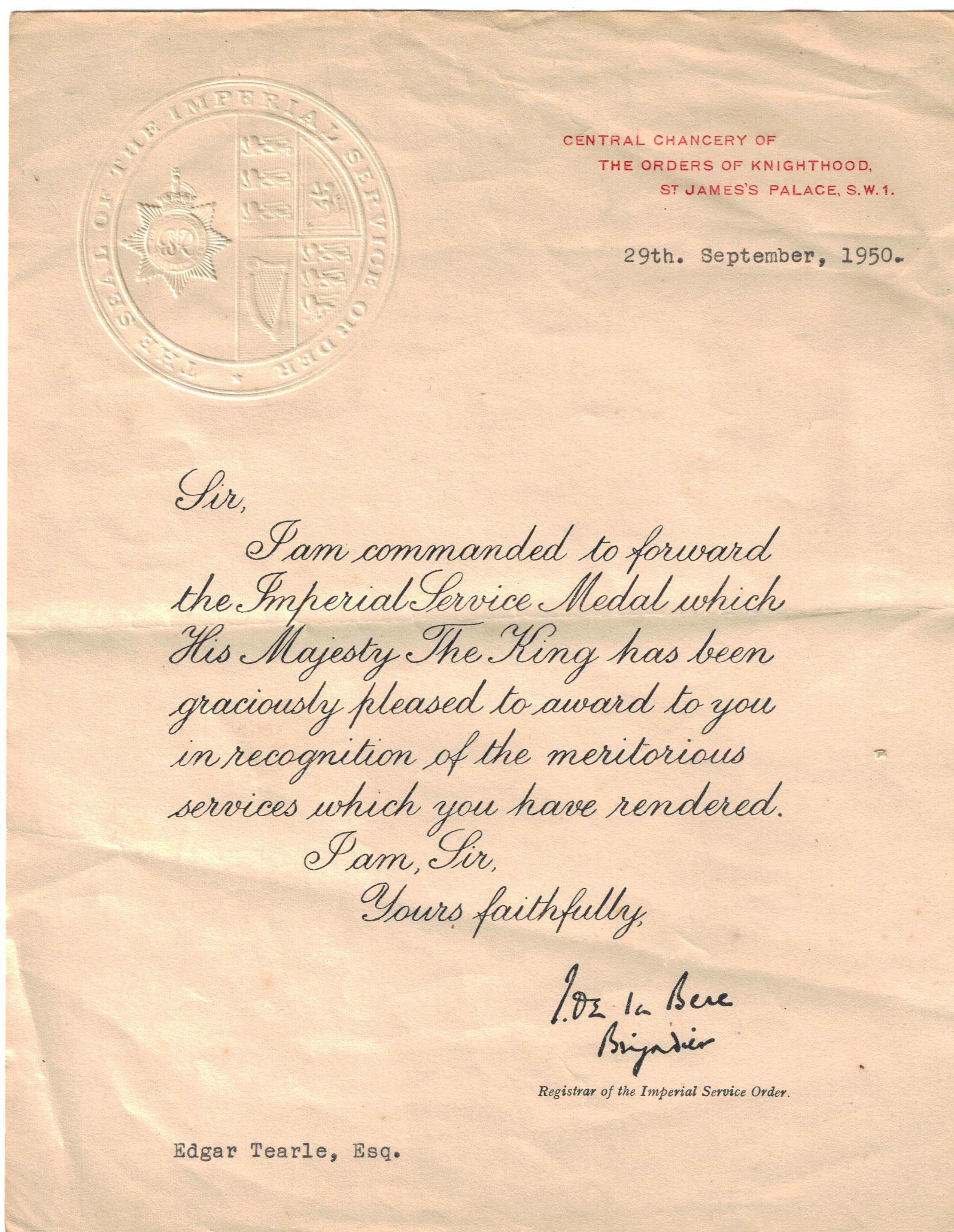

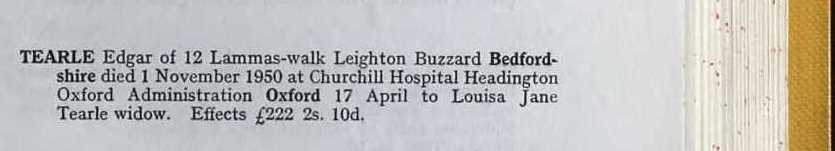

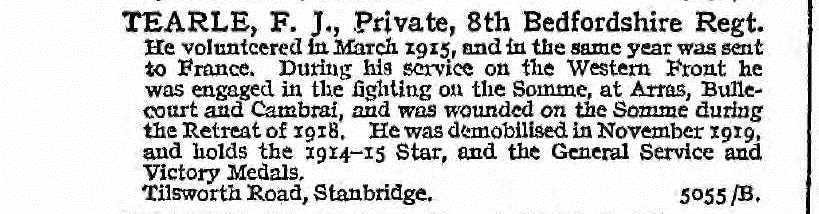

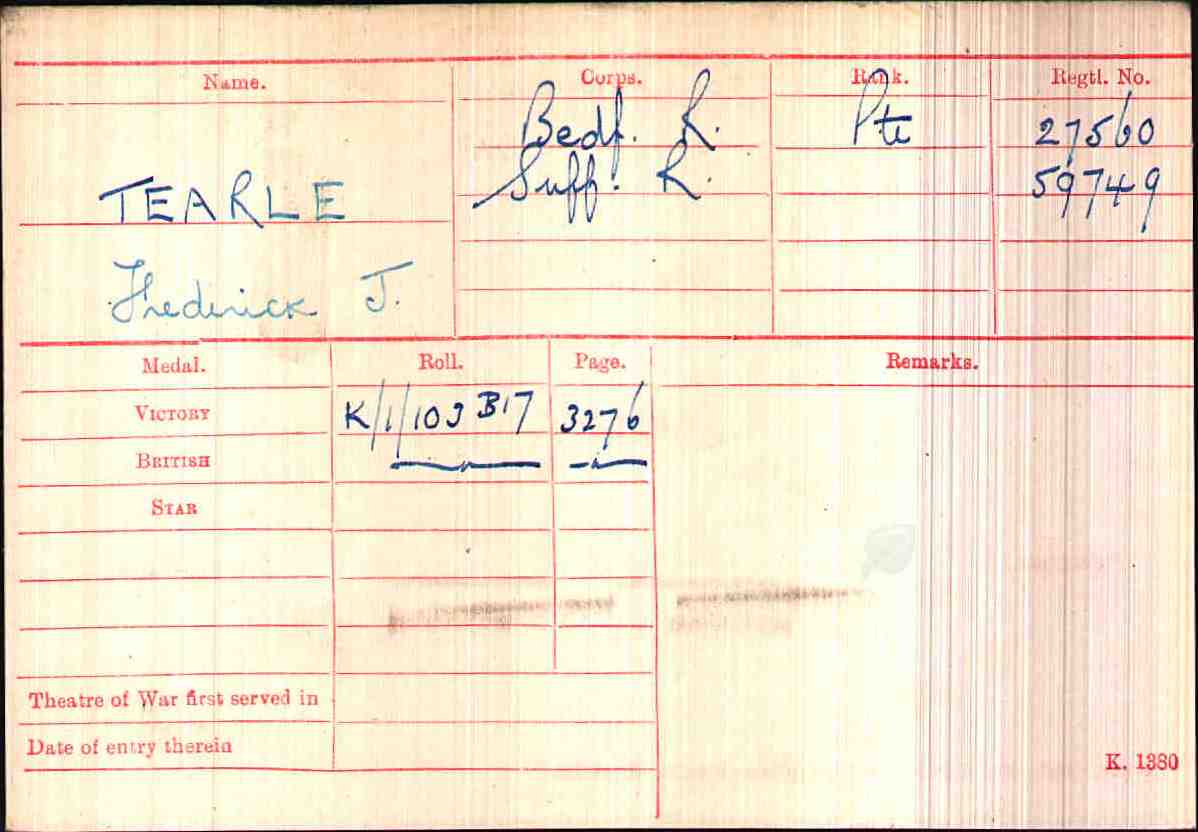

Victor’s service record below includes his citation from the Norwegians.

And on the right are his service medals.

Below is a recent medal from the Russians celebrating sixty years since the Russian relief supply convoys first operated.

“Victor,” I said, “Your grandparents came to live with you in Lostwithiel. Did they die here?”

“Oh, yes, and I can show you where they are buried in the Restormal Rd Cemetery. Would you like me to take you there?”

I would be delighted, but first a little caution. “It’s raining and underfoot is very slippery. With steel replacement knees, are you going to be safe doing this?”

“If I’d wanted the safe option all my life, I wouldn’t have joined the navy,” he said shortly. “I’ll cope.”

We drove round to the cemetery and Victor opened the gate, clipping the latch back. “Over here, the third site from the gate.” He looked around. “I thought there used to be a headstone. There has been some work done in this cemetery and either they have removed it, or perhaps there never was one.”

Above is the unmarked grave of William 1863 and Elizabeth Ann Tearle in the Restormal Rd Cemetery. The site itself is between the two graves in the foreground. We stood for a moment and paid our respect to the unmarked grave. We carefully walked down the mown strip and stopped at William’s headstone. “It’s not very well maintained,” said Victor, “and the council is saying that all memorials that are unsafe in their view will be removed. There are a few that have been pushed over, a few that have fallen over and a few that are in poor condition. I would rather they restored the memorials than simply carted them away. What a loss!”

We stood at William’s headstone silently, each with our own thoughts. “When they put in this path, I reminded them that it ran right over Bill’s grave, but it’s done now, so what can I do?”

“The grave is under the path?”

“Yes. They have moved the headstone a little and it’s not lined up properly, but right here, underneath the path and at right angles to it, is my father’s grave. You know he was the only man in the Lostwithiel Fire Service to be killed in the Plymouth blitz? And he was only 51.”

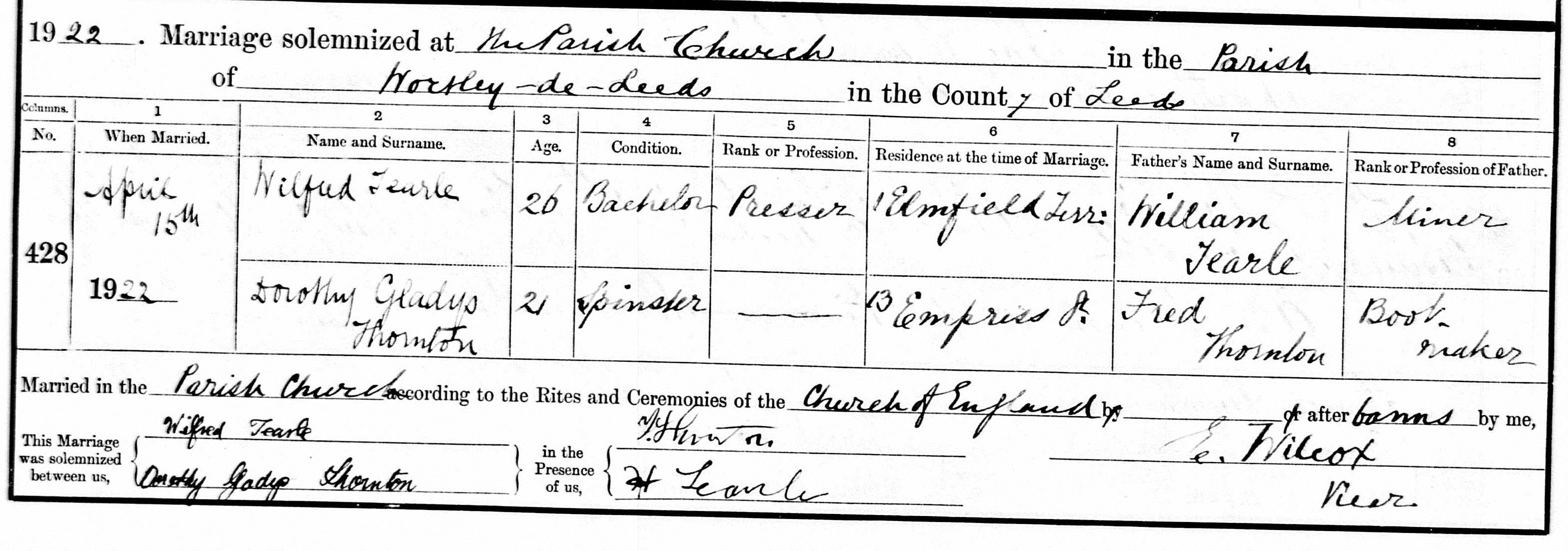

We returned to Victor’s house and he rummaged in a drawer in his lounge for a moment. “You won’t have seen this,” he said. “It’s one of several pictures of my sister Myrtle’s wedding in 1939. The Lostwithiel Fire Service turned out for her guard of honour. My father was so proud of that. The fire service was part of the National Fire Service then and they had their standard uniform – mind you, they still had to buy their own trousers. They were right pleased with their new fire engine, too. You know Myrtle joined the Fire Service after Bill died? That young chap there is Donald Jones. Myrtle and Olive went to Basildon and ran a transport company and it was when my younger brother William joined them that he was killed in the lorry accident.”

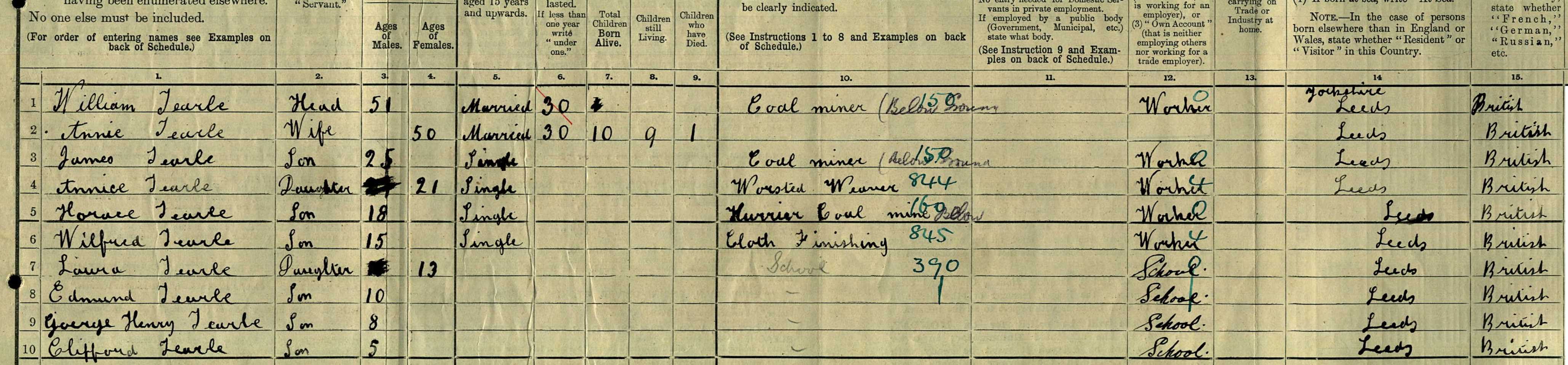

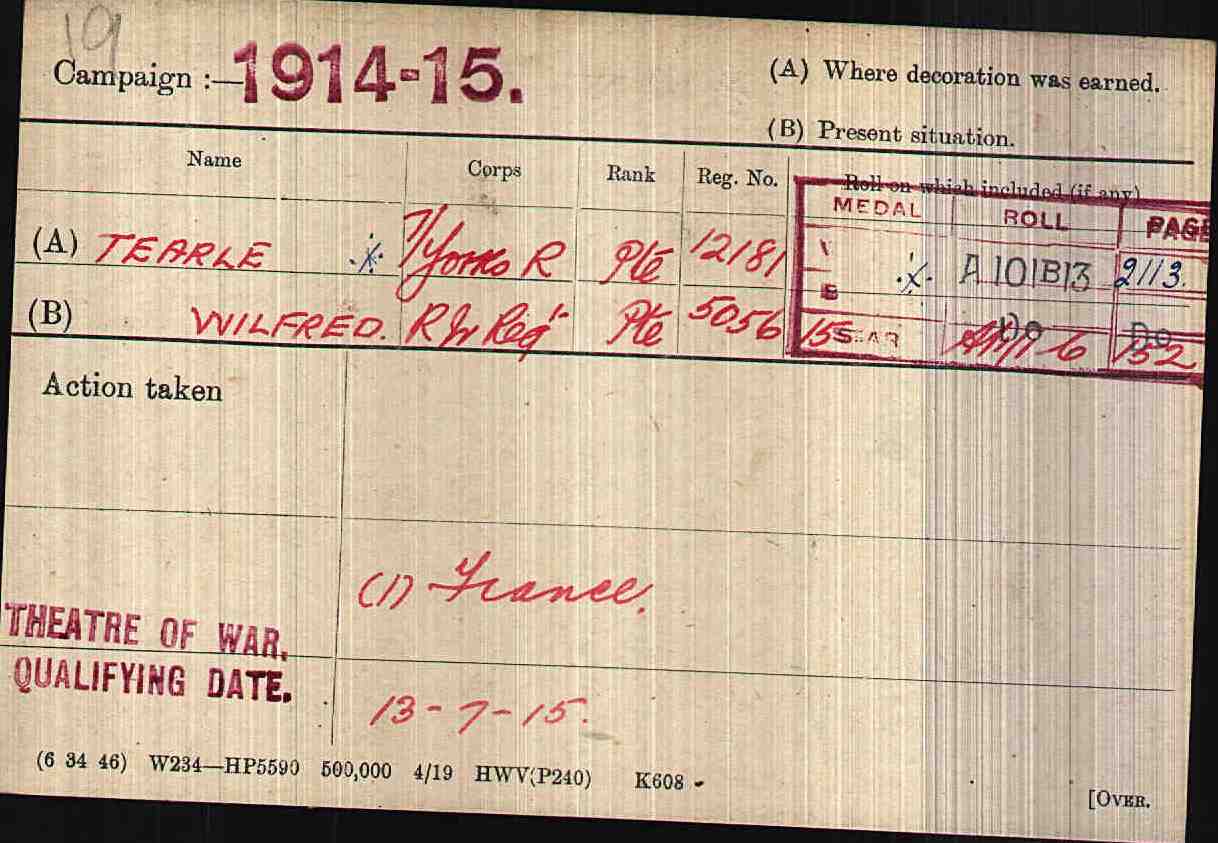

“I have a little present for you, now, Victor,” I said, and I lay out on the table the six pages of the hour-glass chart that I had printed of the branch of William 1863 of Toddington. “Your grandfather was a Toddington man. These days it’s a trucking stop, but many Tearles have come from there.” I pointed to William 1863. “There’s your grandfather, with Elizabeth Ann of Falmouth. Did you know her maiden name, by the way?”

“No,” he said slowly, “I never heard it.”

“It’s there for you now: Elizabeth Jane Cox. And there’s your father, William Alfred John Tearle, who has married Ellen Hambly. This is a history chart so we don’t keep it up to date with births later than about 1920.”

He nodded and scanned William’s family, “Auntie Lizzie, Ellie and Violet. She never married, you know, Violet; she ran Waylet’s cafe on the main arterial into Southend. Aunt Ellie married a chap called Colbeck. He had lost a leg in WW1. They came to Lostwithiel from Putney when I was about seven years old and took in foster children with mental problems. Aunt Lizzie was the manageress of Lyons corner shop in the centre of London. You know I can’t remember her husband’s name. He was killed during the War. Where are you?”

I said, “There are your great-grandparents, John Tearle and Maria nee Major. You can see that John was born and bred in Toddington, as well as your grandfather. Beyond them are William Tearle and Catherine nee Fossey and it was he who made the jump from Stanbridge, where the family originates, to Toddington.”

Victor examined the chart, “Born Stanbridge, died Toddington.” He counted on his fingers, “William, William, John and William; so four generations in Toddington.”

I nodded. “The last William, see how his father is Richard? His wife, Elizabeth, had her first child at 18yrs old in 1796 and her last child, possibly twins, in 1823. Thirteen children in all, and we don’t know how many died as stillbirth or as infants.”

Mavis gasped, “Thirteen children over 27 years.”

“You can see that you are descended from William, a son of Richard and Elizabeth, and I am descended from Thomas, William’s brother. Richard and Elizabeth are our common ancestor. I may be a distant cousin, but we are both members of the same family.” I traced his tree back to John 1610.

“1610,” said Victor. “That’s a while ago.”

“I have some more,” I said and pulled out the 1891 Toddington census return. “Here’s your father, William, just one year old, and you can see in the right margin that he was born in Toddington. Here’s your grandmother Elizabeth Ann, born in Falmouth.” I took out the 1901 Toddington census and he examined it intently. “Here’s your father, now 11 years old and your grandfather, a carrier. For whatever reason, he has left his London job and come to work in Toddington for at least eleven years. A trucking man, too. You can see they have come from London because Elizabeth, Eleanor and Violet are all shown as born in the registration district of Acton, a London address. We can’t always account for everything, but we document what we find.”

Victor and Mavis Tearle, Lostwithiel, 2009.

Over our last cup of tea, he gave me a piece of advice – how to eat a Cornish pasty. “You put the crimped edge into the palm of your hand and start at the pointed end. That way you can fold down the paper bag as you eat it and the pasty will hold the hot gravy in until you make your way down to it. Don’t forget, I’m a baker so I know. Next time you come here, let me know a little more in advance and I’ll make you some pasties. Mavis and I often do for family gatherings and she’s a very good pastry cook.”

I stopped for a moment. “You put the ingredients into the pastry and then cook the pasty? I thought you cooked the ingredients in a pot, like a stew.”

“No!” they said in unison. Victor said, “In the old days you would take your pasty in your pocket with you, all nice and hot, and keep your hands warm on cold winter mornings.”

We collected our gear and loaded it into the car while we thanked Victor and Mavis for their hospitality and generosity. We had met, one way or another, three generations of the Toddington Tearles. William 1863 and his wife Elizabeth Ann nee Cox, from Falmouth, had joined William 1890, the blacksmith and firefighter and his wife Ellen nee Hambly, here in Lostwithiel after he retired from local government. William’s family included Victor, the third generation in Lostwithiel, their grandson and son respectively. I had learnt a great deal about William and his family, not the least because I had met Victor and seen the influence that William had had on him. He is a man of deep conviction and solid humanity. A salt of the earth man, a working man. A man we can be proud of. From the tantalising fragment Richard had supplied, we had uncovered a story of bravery, commitment, patriotism, loyalty and family pride.

Our last view of Lostwithiel – their new fire station.

We went to London to see the Firefighters National Memorial and to record the additional plaque with William’s name. The memorial stands across the road from St Pauls Cathedral, on the walkway approach to the Millennium Bridge.

We went to London to see the Firefighters National Memorial and to record the additional plaque with William’s name. The memorial stands across the road from St Pauls Cathedral, on the walkway approach to the Millennium Bridge.

It already has hundreds of names on it, from firefighters killed in the line of duty fighting fires throughout Britain during WW2. Since William was killed under just such circumstances, then it is right that he is remembered along with the others. We were pleased to see that his bravery in running towards a fire when everyone else was evacuating, and the sacrifice he made in the execution of his duty, has finally been acknowledged at a national level.

The recently added plaque is near the ground but very easy to find. Here is a detail of the plaque with William’s name clearly legible.

The recently added plaque is near the ground but very easy to find. Here is a detail of the plaque with William’s name clearly legible.

The night of 26/27 April 1941 was in the middle of what was to be called the Plymouth Blitz. William was critically injured racing to a fire in Devonport, and died in Bodmin Hospital on 1 May 1941, hence the two dates that Tracy had found.

We are very grateful to the staff and researchers of the Lostwithiel Museum for uncovering William’s story, and for their actions in ensuring that William was remembered for the work that had cost him his life.

Post script

I have uncovered a potted, but detailed, History of the HMS Onlsow, part of a much larger piece on the ships of the Royal Navy written by Lt Cdr Geoffrey B Mason RN (Rtd)

* After the allied landings in Normandy (operation NEPTUNE) in May 1944, the Onslow was leader of a flotilla ordered to patrol the English Channel to keep secure the Allied hold of the French coast. The torpedo strike Victor recounted above happened on 18 June 1944.

* On 5 June 1945 the Onslow (and others) escorted the HMS Norfolk to Oslo, taking home the Norwegian king, for which there have been celebrations in Trafalgar Square every Christmas since.

* HMS Onslow was deployed by the Pakistan Navy as the TIPPU SULTAN until 1957, being returned to Royal Navy duties as an anti-submarine frigate in 1960. She was finally taken off service and scrapped in 1980.

* HMS Exeter was one of the fleet, which included the New Zealand cruiser the HMS Archilles, that famously won the Battle of the River Plate, in Dec 1939. There is a wonderful picture of the huge amount of damage she sustained during this battle. She was then engaged in the Battle of the Java Sea with the Australian Navy against the Japanese and after a great deal of fighting during February, was finally sunk by torpedo on 1 March 1942. This was a towering warrior of a ship and a true friend of the ANZACs.

Ewart Tearle, May 2009

Epitaph:

August 2016

I received a very tearful call from Mavis in September 2011 to say that Victor had died, and Elaine and I determined then that we would visit Mavis, see Victor’s grave, and pay our respects to his memory, as the last chapter in this story. In these August holidays we have visited Lostwithiel and made good our intention. Mavis was delighted to see us and coincidentally we met Vivienne, Victor’s eldest daughter.

The road to the Lostwithiel cemetery is as steep a climb as a car can be coaxed. We looked for Victor’s grave, but found that he had been buried with his first wife.

Here is their grave:

Grave of Joan and Victor Tearle

Here is the text on each of their headstones:

Headstone of Joan Tearle nee Goodman

Headstone for Victor Tearle

and here is the view to their grave from the cemetery gate.

Joan and Victor Tearle grave location from Lostwithiel cemetery gate.

You can see the vase of flowers in the middle ground on the left diagonal from the front headstone.

I cannot overstate the admiration I have for Victor, and for his father, William AJ Tearle. Mavis said that at heart Victor “was just a Cornishman,” and if that means he was a generous, full-hearted man, with a love of life and a deep appreciation of his obligations, then we can leave that thought as his epitaph.

were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”

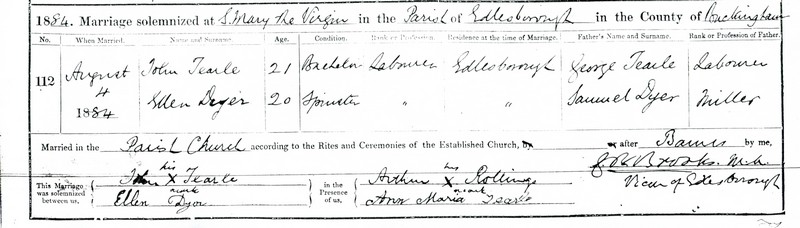

were made in France. The cutlass blade says “Souvenir of Calais” and Bill had the handle engraved “To my dear father.”