Ethel had deep concerns when Arthur told her he was going to join the army and fight in the war that was raging across Europe in 1914.

“You’re nearly 35 years old, why do they need you?” She had read the newspapers and had become increasingly alarmed at the lists of casualties being published every day. “You’ve got three children, do you just waltz off and leave me to look after them by myself? If you are killed who then cares?”

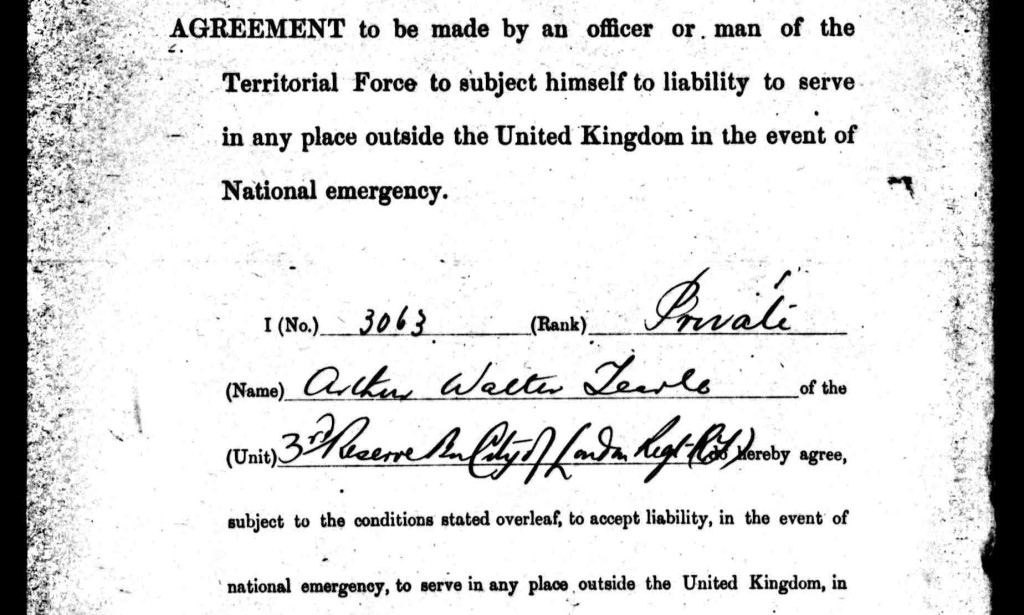

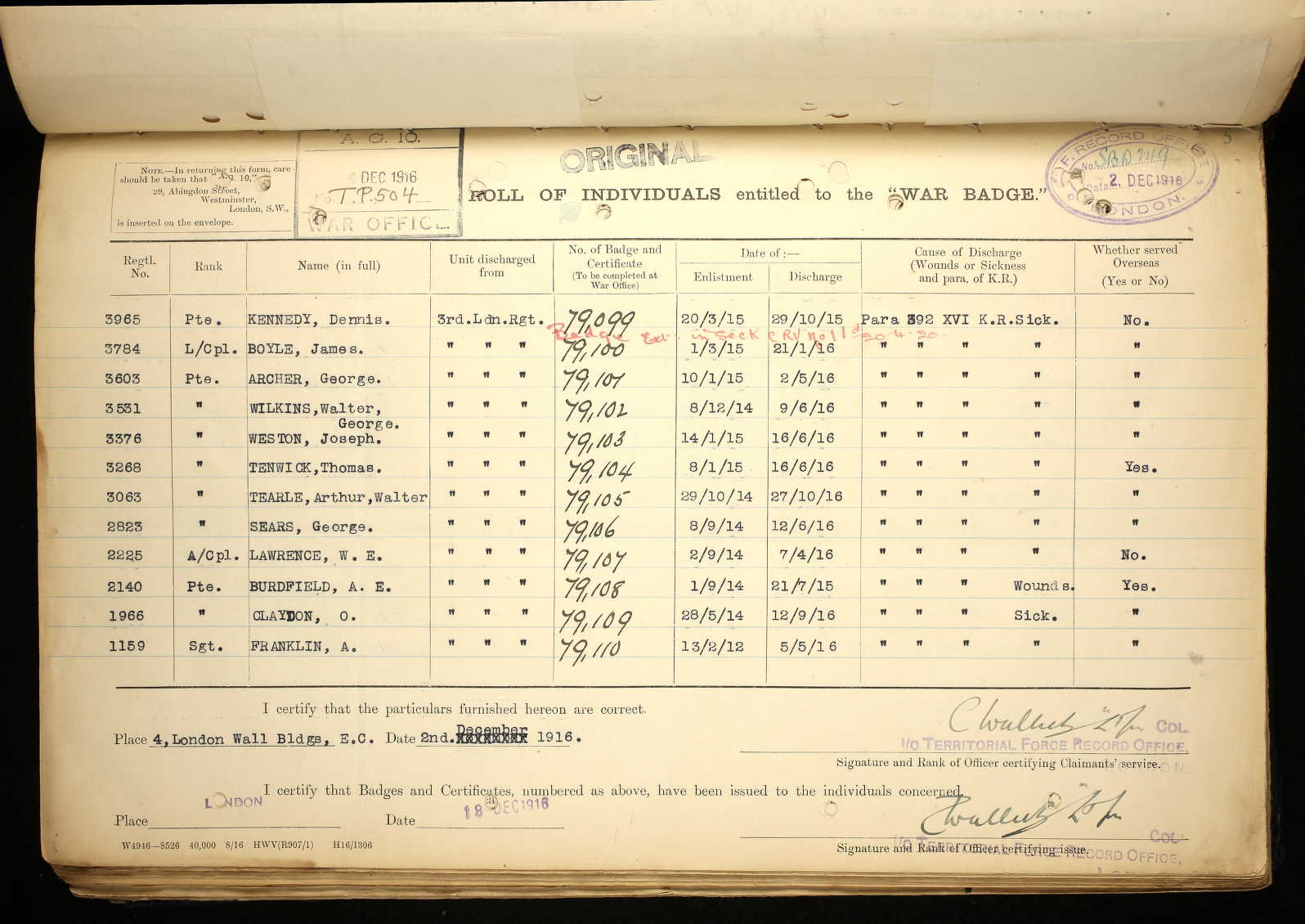

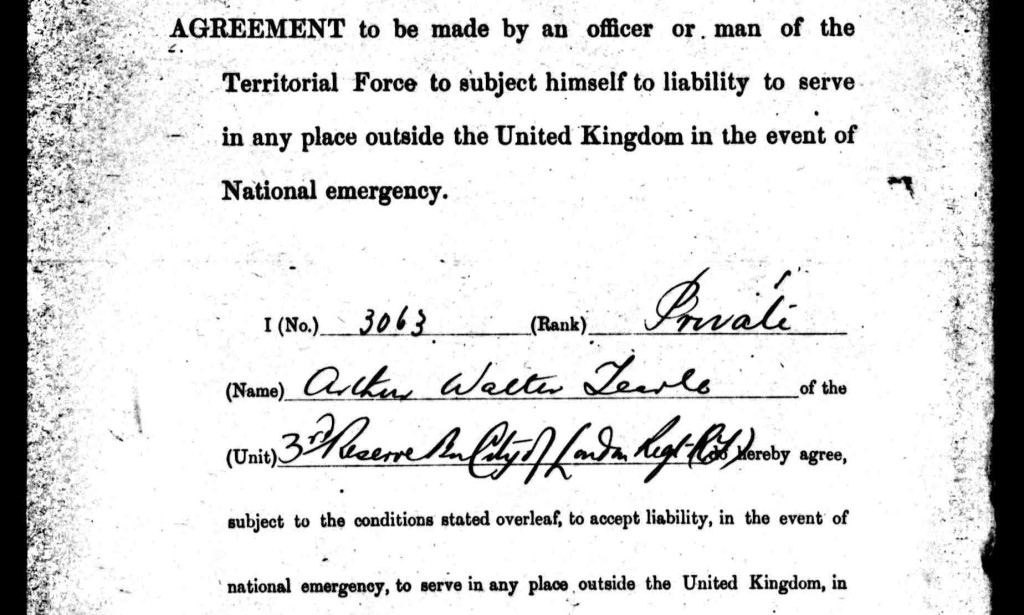

She knew she was repeating what every mother had said to their sons, but she was sure this was different – Arthur wasn’t a fit young man looking for adventure, he was working for a well-established educational publisher and he had a family to care for. Not to mention Ethel herself. She had not married him in the Prince of Wales Rd Wesleyan chapel in 1898 to see him disappear in 1914, killed in action in some muddy hell-hole in France or Belgium. Her sister Edith had been her bridesmaid, Arthur’s own sister Minnie had signed the register, surely they would not approve of this? She did not have time to consult them; on the 29th Oct 1914, Arthur showed her a copy of the form he had signed in the Edward St Recruitment Office not far from where they lived.

“I’m in the Territorials,” he said. “Mind you, it’s only a reservist battalion.” He looked at her hopefully, waiting for approval.

“3rd Reserve Battalion (City of London) The London Regiment” she read out. “We’re not in the City. Why them?”

“They recruit over here. And besides, we were married in St Pancras, remember? That’s where the HQ is.” His chin went up, “I’m in the Royal Fusiliers.”

“Reservist, eh? Listen to this.”

She read out a short note from the form

“… to subject himself to liability to serve in any place outside the United Kingdom in the event of National emergency.”

“What do you think the War is? It’s a National emergency. The minute they get hold of you, you’ll be outside the United Kingdom all right!”

Arthur Walter begins his army service

Why could he not see this?

She looked up from the form and saw disappointment, and even an echo of her own exasperation, on his face.

“I know you’re doing the right thing,” she said slowly, “but this is going to be hard for us. You, me and the children. When do you start?”

“Tomorrow morning.

The 3rd (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment. (The Royal Fusiliers)

Enlistment numbers show the stark reality of the sheer quantity of men enlisting for what we now call World War 1, and which our parents referred to as The Great War. The 3rd Battalion enrollment numbers rocketed from 1947, the enrollment number of the man who enlisted on 3 May 1914 to 3148, being the enrollment number of a man who enlisted on 18 Dec 1914. A total of 1201 men for one battalion in just seven months. After 1916 many regiments and battalions were disbanded and re-organised and the numbering system became chaotic and non-sequential, but during the months above, the numbers are orderly and sequential. The Long, Long Trail has a section on the London Regiment, and the 3rd Battalion, that gives further background into the regiment that Arthur had just joined

The Long, Long Trail notes that the 3rd Division of each regiment consisted mainly of Section D Reservists, who were normally soldiers who had fulfilled their 5 years service in the regular army and were waiting out their 5 years on reserve.

“All those surplus to the immediate needs of the regular army battalions were posted to the Special Reserve. Thus the (usually) 3rd Battalion of each regiment was massively and very rapidly expanded. Very large numbers of men passed through the SR battalions before being posted to the regular units.”

The record is silent as to where Arthur was trained (most of the London Regiment was trained on Hampstead Heath) but it is quite specific that he was “Home,” as the army calls it, in basic training, from 29 Oct 1914 to 22 Dec; just 55 days. On the 23rd Dec he was on a ship, bound for Malta and the Egypt Theatre of War.

“Reservist?” A shocked Ethel mourned the fact that Arthur could not have Christmas with his family.

Gallipoli

Malta was not under direct threat in 1914 and 1915, but it was a strategic post in the Mediterranean and housed hospitals for repatriating the wounded as well as supply depots for onwards goods and munitions deployment. Whatever he was doing in Malta, and the record is also silent on this, Arthur worked, or trained, perhaps, for 106 days until, on the 7th Apr 1915, he was posted to the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF), to fight in the Dardanelles Campaign. This engagement now forms part of the history of both the London Regiment and the ANZACs. Gallipoli is where New Zealand became a nation and ties with Australia were permanently bound. The 25th April each year is a National Day for both countries.

Vice-Admiral Sir John De Roebecks describes the landings at Anzac Cove and Cape Helles on 25 Apr 1915. Since this was an amphibious landing, I assume that Arthur spent the time between 8 April and 25 April in training for the assault on the Gallipoli beaches. The Vice-Admiral does not specifically mention the 3rd Division but he does say the 2nd Division (Royal Fusiliers) embarked on the warship the Implacable and landed at 07:00 with no casualties, the accompanying warships having given excellent covering fire.

“The nature of the beach was very favourable for the covering fire from ships, but the manner in which this landing was carried out might well serve as a model,” said the Admiral. I think that Arthur was amongst these men. The rest of the Gallipoli campaign is well covered by the many histories written about it and The Long, Long Trail has a very balanced view of the conflict over the entire peninsula.

It is worthy to note that John Henry Tearle 1887 of Hatfield (Service number: 9054) was also there. He was killed on 29 June 1915 and is memorialised on the Hellespont Memorial. I assume he was killed in the Helles area, so he probably survived the original landings and was killed in the Battle of Gully Ravine, which began on 28 June 1915. I shall explain the relationship between John Henry and Arthur later.

Conditions in Gallipoli were appalling. Fighting was almost hand-to-hand and the bodies could not be buried, food was scarce and munitions poorly serviced. Death, disease and sickness were rampant, yet there are legends of donkeys carrying the dead being allowed free pass through enemy lines, of truce hours when the dead were buried and soldiers took the opportunity to swap food parcels with the enemy – for instance, tomatoes were swapped for potatoes. They were fierce fighters, but there was a time and a place for fighting and when there was a truce, then you did not fight.

For almost an entire year the two sides fought over hills and rocky outcrops, trying to force an advantage. Finally, Churchill realised this was no back door into Germany and more pressing concerns drove his attention elsewhere. Gallipoli was the worst disaster of WW1.

ANZAC graves, Lone Pine, Gallipoli.

Copyright Genevieve Tearle 2004

Gallipoli was also nation-building for the Turks. Their now legendary leader, Attaturk, built his nation firmly on temporal lines; there would be no blurring of church and state. In 1934 he built a memorial to the events of the Dardanelles Campaign and he made the following promise:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives…. You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours…. You the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.”

Thousands of Kiwis and Australians who visit ANZAC sites every year in honour of their grandparents take heart from this message.

In Dec 1915, Arthur was struck with typhus. He was looking forward to the evacuation, which had been ordered on 8 Dec 1915, but this was a bitter blow after the months of fighting he had endured. The Long, Long Trail concludes that 260,000 Allied troops were killed, and 300,000 Turks. They had fought themselves to a draw.

Arthur was evacuated to Valletta Hospital in Malta, where he started his convalescence after his initial treatment for typhus. He looked at the stone walls and the high, vaulted ceilings from his cot and saw a surgeon with a small group of on-lookers standing around the soldier’s bed next to him.

The surgeon was wearing a bloody apron, his badge of office since the days of the barber-surgeon, and he dropped the chart he was reading onto the soldier’s bed and turned to Arthur.

“This man contracted typhus in Gallipoli and has done well to come through it as far as he has,” said the surgeon to the little throng, grouped around the bed, one in a seried rank of beds, crushed into the long, narrow room. He turned his back to the window, the better to read Arthur’s chart in the gloom. “However, he has now developed gastritis and this will prolong his treatment, mostly with a change of diet. Gastritis is a common complaint after a serious trauma such as Enteric Fever.” The surgeon used the army term to ensure his students were up to date with the latest advances in military medical technology.

They moved off, satisfied with Arthur’s progress. His stomach was on fire and he gritted his teeth at the waves of pain and nausea. “I suppose he thinks I’m lucky to be alive,” he said. “What does he mean about a change of diet?”

“No Friday curry,” said an orderly.

C Savona-Ventura, in a scholarly but not very well organised essay on the Military Hospitals of Malta (The Nurse of the Mediterranean) notes that during the Gallipoli campaign 2500 officers and 55400 troops were treated at Valletta. This hospital has a long and chequered career, involving an essay on its improvement from none other than Florence Nightingale herself, charging the hospital with unsanitary conditions, poor treatment of patients and understocking of supplies. The British government set up a commission and recommendations were made, but nothing was actually done. It is generally agreed that Valletta was insufficient (and always had been) for the uses it was put to. It was here that Arthur had contracted gastritis, which is a nasty inflamation of the stomach, probably including a peptic ulcer.

He was returned to England where he spent time in Chichester Hospital, Lewes, then Braydon Hospital, then a spell in Newport Pagnell. He returned to duty on 2 May 1916, but was unable to work.

He was examined at Hurdcott Camp Hospital in Wiltshire. This was originally set up for various London Rifle brigades, but in August 1916 it was taken over by the Australians who used it for convalescing soldiers who would be there for six months or more. In the hills around Fovant, where Hurdcott is situated, you can see The Fovant Badges. These are regimental badges cut into the chalk and still tended today. The 6CLR (6th battalion, City of London Regiment) is clearly there. It will serve to remind us of the London Regiment.

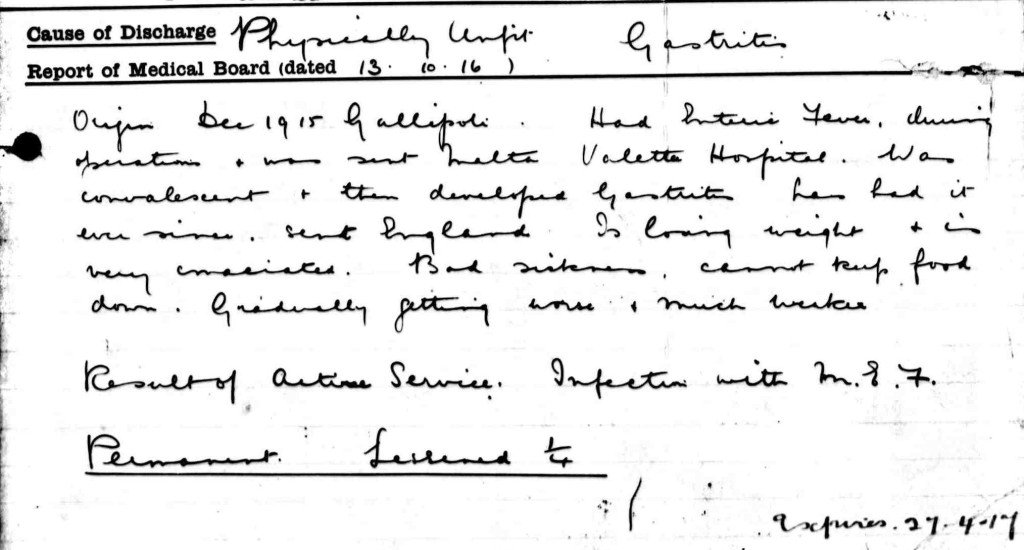

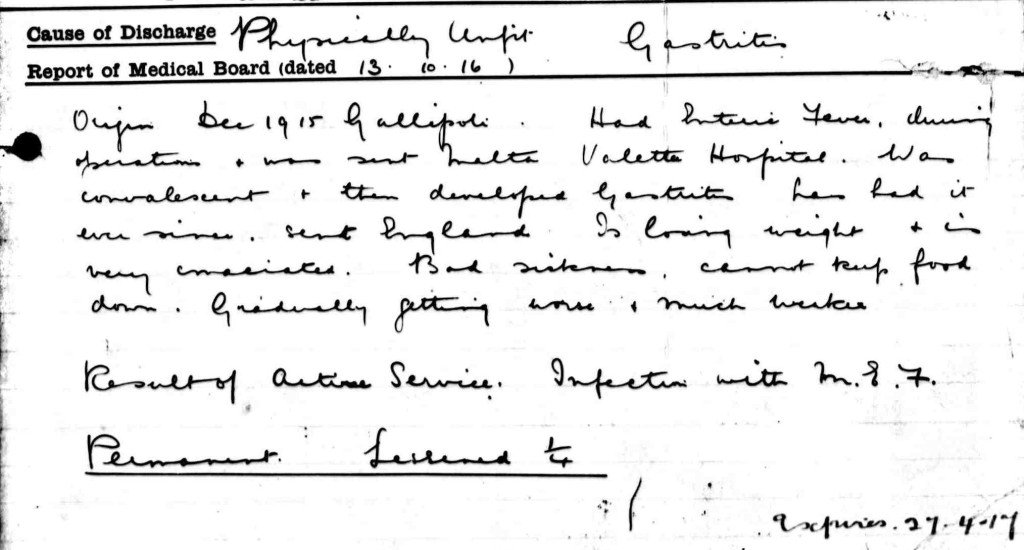

On 10 Oct 1916, they reported on Arthur, and two days later, he was recommended for discharge from the army as “No longer physically fit for active service.” I have reproduced a short part of the report, below, but let me transcribe it, since it makes grim reading.:

“Origin Dec 1915 Gallipoli. Had Enteric Fever, during operations, & was sent Malta Valetta Hospital. Was convalescent and then developed Gastritis. Has had it ever since. Sent England. Is losing weight & is very emaciated. Bad sickness, cannot keep food down, gradually getting worse, and much weaker. Result of active service. Infected with MEF Permanent.”

On the 27th Nov 1916, he was formally examined and discharged. He had been in the army on active service for two days short of two years.

This report from Chelsea Hospital also tells us that he had three children: Hilda Alexandra, born 1902, George Ewart born 1909 and Winifred Agnes born 1913. A Children’s Allowance of 1/6d per week had been paid for each of them, I assume in addition to his 3/6d weekly pay as a private in the army. He was recommended for three medals – the Victory, The British, and the 1914-1915 Star.

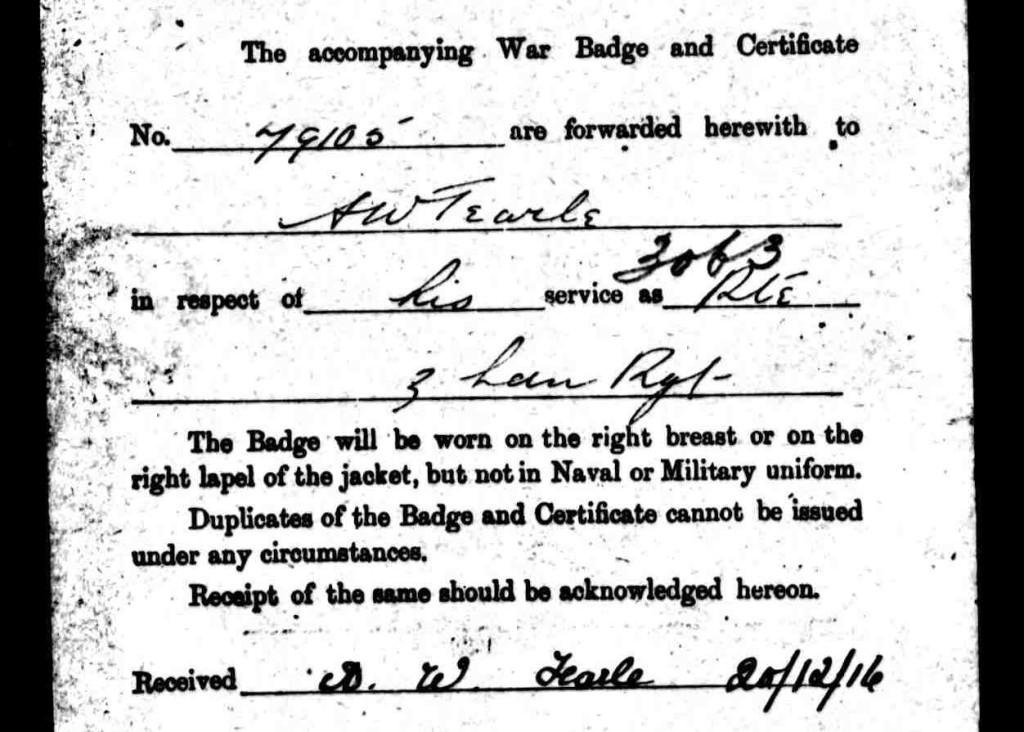

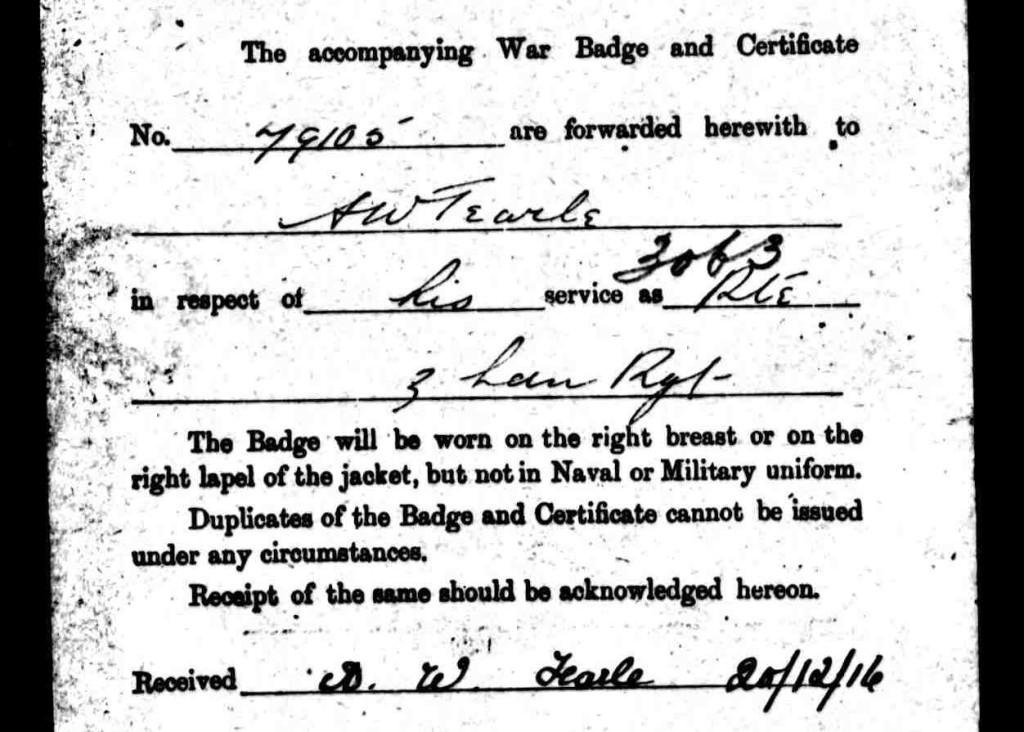

These may have been the same medals as many others received at the end of WW1, but they cannot disguise the fact that Arthur started service at the beginning of the War (hence the 1914-1915 Star) and served overseas for a significant part of his term of service. Nor can they hide the sacrifices he made and the enduring pain he, and his family, suffered as a result of his original decision to help in the effort to defend his country. On the 20th of Dec 1916, Arthur signed for the receipt of the first of his medals. Note that it states that “The Badge will be worn on the right breast or on the right lapel of the jacket, but not in Naval or Military uniform.”

Arthur Walter receives his Silver War Badge

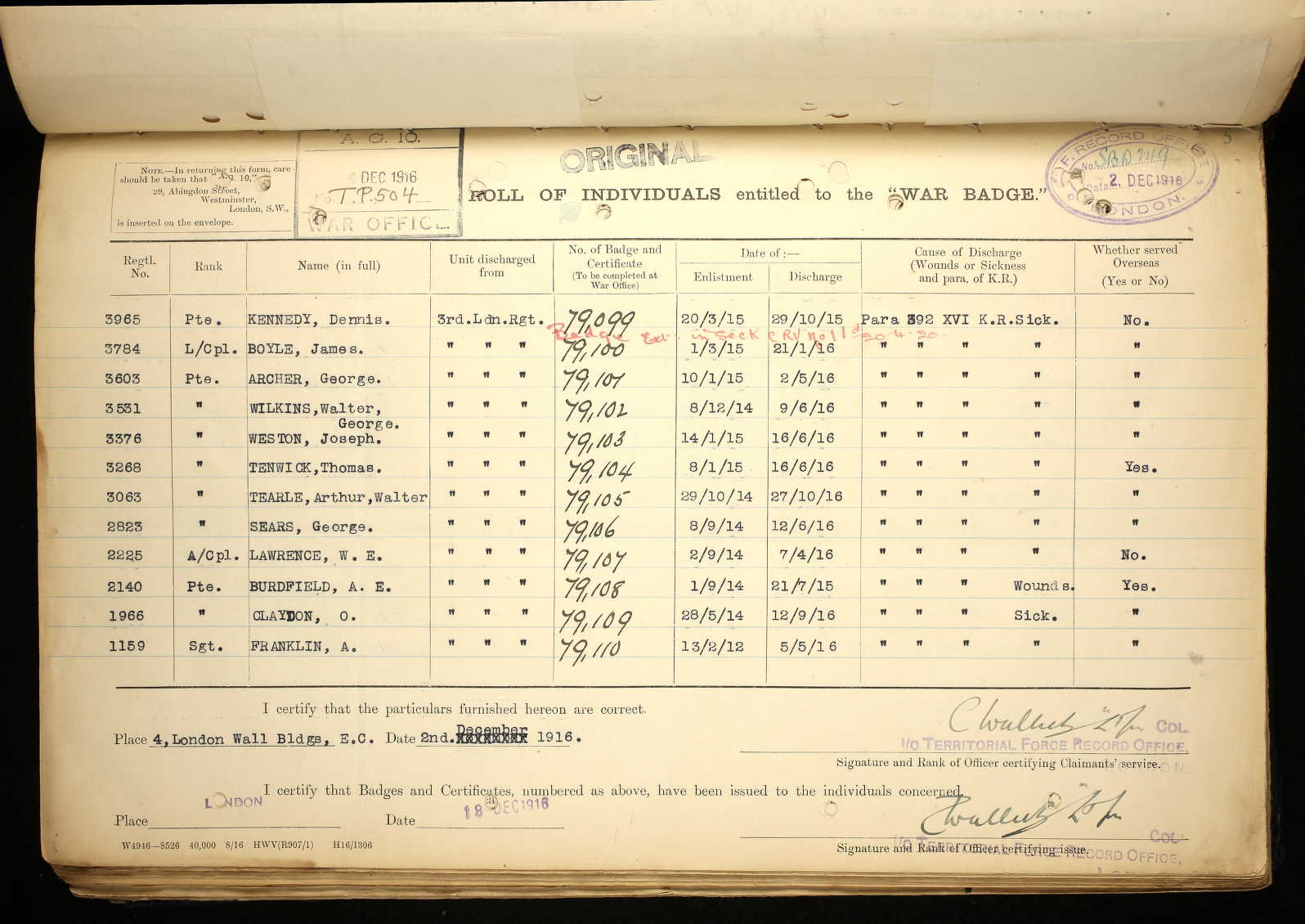

Here is the record the army used to ensure his award was correct.

Arthur Walter Tearle WW1 Silver War Badge

On the 24th Aug 1918, he received his King’s Certificate, which was the formal acknowledgement that his king and country would no longer require him for any kind of active service. I do not know if Arthur had recovered enough from his gastritis for the army to conclude that it was no longer their problem, or if the army paid his pension until the end of his original contract, or whether he was actually fit enough to resume his profession as an educational publisher’s assistant, but on the 20th Nov 1919, his army pension was stopped: “No grounds for further award.” All ties with the army were now cut and five tumultuous years in the military were over.

According to Arthur’s grandson, his girls had no children, but George had a family, and one of his boys bears the name Ewart, and that son has a boy called Ewart as well. Quite where the name comes from in Arthur’s family is a mystery, but mine comes from the Ewart family of County Antrim in Northern Ireland, via my maternal g-grandmother. I am not familiar with other members of Arthur’s family to know if their Ewart is family, or a name that Arthur or Ethel met in London.

I am now in a unique position to move backwards into Arthur’s past, to see into his family history for as far back as three hundred years, and possibly to see what the links are between the families that we call the Willesden cell – in other words, those families living in London NW10.

Arthur’s past

Here are my notes on Arthur in the 1901 census in London:

1901 = Arthur 1881 St Pancras Ethel 20 in Kentish Town LON

My other notes will follow this format:

1901 refers to the census year,

Arthur 1881 St Pancras references the person of interest on that census page, the year he was born and the place he was born.

Ethel 20 (and others) lists the other members of the household and their age.

In Kentish Town tells us where they were living. If the location is not immediately obvious, the I have added an identifier (LON – London).

Arthur and Ethel are fairly newly married, given that they did so when they were just 17 (I have the wedding certificate) and they are living at 30 Grafton Rd, Kentish Town. Arthur is a Publisher’s Storeman. Arthur’s wedding certificate stated that his father George Tearle was a Railway Platelayer, so that would account for their presence in Kentish Town – George had found work at one of the major railway workshops of the 19th century.

Arthur’s birth was registered in the first quarter of 1881, but I’m fairly sure he was born in the Dec of 1880 – the birth certificate would solve that question – but there is no doubting his parentage; George Tearle 1844 born in Stanbridge, Beds, and Lavinia George, born 1846 in Mursley, Bucks. In one jump, then, we are back to the traditional birthplace of almost all the Tearles in the world today. I found George in 1901, too:

1901 = George 1844 Stbg Lavinia 55 Annie 25 William 21 Ethel gd 2 in Kentish Town LON

They are living at 25 Ashdown St, Kentish Town, and this return tells us quite a lot about George’s family – for instance, that since Annie was born in Kentish Town, then George has been working for the railways for at least 25 years. Given that Arthur does not list Ethel amongst his children for his Children’s Allowance, then I assume that Ethel, 2yrs old and George and Lavinia’s grandchild, is Annie’s daughter. Let’s keep going back:

1891 = George 1844 Stbg Lavinia 45 William G 11 Arthur W 10 in Kentish Town LON

The family is living at 7 Ashdown St, Kentish Town. This may be the same house as in 1901, because since the Post Office gave the houses the numbers in the first place, it’s possible they simply changed the numbers. William and Arthur are both at school, and both were born in the district of St Pancras, which covers Kentish Town.

1881 = George 1844 Stbg Lavinia 35 Sarah 9 Annie 7 Minnie 5 William 1 Arthur 2m in Kentish Town LON

George is a Railway Labourer and it looks as though Sarah, the eldest, was born in Middlesex, Kilburn, though I’m not quite sure what that tells me except that by age 27, George and Lavinia were no longer living in Bedfordshire. Annie and everyone after her were all born in St Pancras so George has taken up his railway job by at least 1872. There is Minnie, by the way, who officiated at Arthur’s wedding, and just a little aside; they are living in Prince of Wales St, which was the address Ethel gave at her wedding, and it was also the address of the Methodist chapel where the wedding was held. So that’s how Arthur and Ethel met.

1871 = George 1844 Stbg Lavinia 25 in Willesden Mdx

Now this is really interesting – George and Lavinia, with no children, are in Willesden, and George is a Platelayer on the railway. He is 26yrs. He is fresh from the country, so who else is in Willesden? No one. Was he the first? It seems that he may have been.

In 1881 Jonathon 1862 Stbg is there, a porter for Thomas James Shackle, a “Modeller in Sugar.”

In 1891 there is a list: Annie 1874, George’s daughter; Hannah Estaffe, nee Tearle 1865 of Stanbridge; John 1856 and Elizabeth and family; Jonathon again; Zephaniah 1869.

And the same again in 1901.

I shall come back to their interrelationships once I have traveled a little further back in time.

In 1861, there is a completely different picture as we approach the roots of Arthur’s tree. We are on the Eggington Rd, Stanbridge, John and David Flint, the bakers, are next door, young Frederick Janes the butcher (only 26 and already a stand-alone businessman) with his wife Rebecca, is two doors away, but we are standing in front of Mary Tearle’s house.

1861 = Mary 1805 wid of Toddington, John 21, Ann 19, George 16, David 11, Elizabeth gd 4, all born in Stanbridge.

Mary is a char woman, originally from Toddington. She washes clothes, cleans houses and probably the local pubs; this is hard physical work and the chemicals she has to use cause permanent redness and angry welts on her hands and arms. She is already a widow, even though only 56. We now know George has an elder brother John, a younger brother David and a sister Ann. I checked the 1871 census to see if Mary was still there:

1871 = Mary 1805 Tod David 21 Elizabeth gd 14 in Stbg

She was. Her son John, now 31, lives next door and her grandson Levi 1850 (my g-grandfather) is next door on the other side, working as a blacksmith with William Thompkins.

1851 = Thomas 1807 Stbg Mary 46 John 11 Ann 9 George 6 David 1 in Stbg

1851 = James 1828 Stbg p1 Mary 23 in Stbg

1851 = James 1828 Stbg p2 Levi 8m in Stbg

In 1851 the whole picture becomes clear. Let me show you how clear: in the picture below of Stanbridge church with the John and James headstones in the foreground, the one on the left is George’s elder brother, John 1840 “For 60yrs sexton of this parish” and on the right is James 1827, my gg-grandfather and the father of Levi 1850, above, the blacksmith. He is also George’s eldest brother.

I’m not quite sure how all of this works, but John was a Methodist and worshiped in the chapel next to where the school still stands. However, he had the job as sexton of the church and yet still called himself an Ag Lab on the census. Either his job was entirely voluntary, or Ag Lab, as an occupation, also covered the work of a church caretaker. This is the family of which Arthur Walter Tearle 1880 of London is a member. You can go to Stanbridge and touch their headstones.

Next door in 1851 lived Abel 1810, Martha nee Emmerton and their family.

Abel’s grandfather was Joseph 1737, the father of one of the major Tearle branches, while Thomas’ grandfather was John 1741, Joseph’s brother and himself a founder of a major Tearle branch. One step further back is their father, Thomas 1710. We are now back to the ancestors (Thomas 1710 and Mary nee Sibley) of almost every Tearle alive today. If you read John L Tearle’s groundbreaking work “Tearle; A Bedfordshire Surname” you will be able to see how John L took the family roots back to John 1610 and his wife Joan.

I have a little snapshot of Lavinia George and her family in Mursley, Bucks in the same census, on the other side of Wing, on the A418, close to Wingrave, which certainly has Tearle connections. Use the Search function to see the Wingrave stories.

1851 = Lavinia George 1846 Mursley, Bucks

We have a final glimpse in the 1841 census of Thomas and his family. James 1828 is already in service.

1841 = Thomas 1811 Beds Mary 1806 William 9 Emma 3 John 1 Stbg

6 doors away from them as they live on the Leighton Rd, is John 1791 and Elizabeth nee Mead. He is Abel’s brother.

1841 = James 1828 Beds MS in HeathnReach

This is Thomas’ boy, James, my gg-grandfather working as a manservant in Heath and Reach – not too far from Stanbridge, but I would still think it was an uncomfortable distance from home. He grew up to marry Mary Andrews 1830 of Eggington, albiet they married as minors, and she had quite a colourful career which you can read about from her link.

So let’s go back to Willesden and see if we can tie up some of the relationships we have discovered there.

The Willesden cell

We now know, with some surprise, I must admit, that George 1844 from Stanbridge, was the instigator of the Willesden cell. Upon reflection, I think it grew because George was the first. In finding a job on the railway he had blazed the trail for others who had to leave the country and farming life as rural England became more mechanised and fewer farm workers were needed. He had found a stable job with reasonable earning that did not require very much education – a kind of transition job between skilled but poorly educated farm work and the increasing demands for literacy in the urban workforce.

The memorials to John 1840 and James 1827 are close together.

Here are closeups of the two headstones – first, John the sexton:

John Tearle and Maria nee Bliss headstone, Stanbridge.

Then James Tearle, his brother:

James Tearle and Mary nee Andrews headstone, Stanbridge.

Looking at the detail of the movement to London, there are certainly links between the members of the cell:

1881 – Jonathon 1862, Stbg

He was a son of William 1832 and Catharine nee Fountain. George, John (the sexton) James and William were all brothers. In fact when James died, his wife Mary nee Andrews married William. William was also a railway worker and had been since at least 1861. Perhaps he showed George the benefits of working on the railway. So Jonathon went to London and lived near his uncle while he became used to the urban ways of doing things. He married Alice Kearns in 1882 in Marylebone, and their son, James Harry Tearle 1891 was killed on the Somme in 1917.

Jonathon and George certainly had a common ancestor – Thomas 1807 and Mary nee Garner.

1891 – Annie 1874 Stbg – George’s daughter. She had moved across London to be with her dad.

1891 – Hannah Estaffe nee Tearle, 1865 Stbg. Hannah Married James Estaffe in 1888, in Stanbridge. Her mother was Mary Ann 1841, dau of John 1823 and Eliza nee Irons.

1891 = John 1856 Stbg Elizabeth 35 John 12 Louisa 8 Arthur 4 George 2 Ethel 4m in Willesden, Middlesex.

This is Hannah’s family from Stanbridge; John 1856 and Elizabeth – I do not know her maiden name. Hannah is the grand-daughter of John 1823 and Eliza nee Irons. John’s mother was Mary 1803, daughter of John 1770 and Mary nee Janes. His grandfather was John 1741, who was the father of Thomas 1807. John 1770 is the brother of Richard 1773 (who married Elizabeth Bodsworth) who was the father of Thomas 1807. It’s possible that John 1856 knew all this, but it’s equally possible that he had village connections, and being from Stanbridge and a Tearle, opened up London for him, with George and Jonathon’s help.

1891 – Jonathon again

1891 – Zephaniah. He was the son of Jane 1844, dau of John 1823 and Eliza nee Irons. Jane was the sister of John 1856. So Zephaniah is also a grandson of John and Eliza nee Irons. Once John 1856 and Hannah arrived, it was easier for Zephaniah to make a living in London.

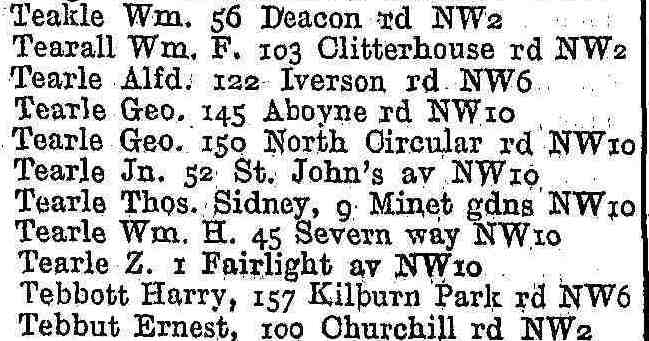

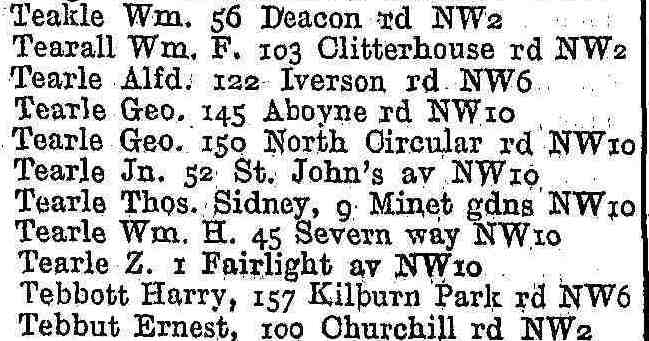

The picture does not change in 1901 so I have a clip from a directory of 1936, and I’ll leave it to you to suggest who these families might be.

Tearle families in NW10, 1936

Here are the families as listed in the directory:

Alfred in Iverson Rd

George in Aboyne Rd

George on the North Circular

John in St Johns Av

Thomas Sidney in Minet Gdns

William H in Severn Way

And it is certainly Zephaniah in Fairlight Av, Harlesden, because that was his address when he died in 1951.

The Gallipoli cousins

Let me now fulfill my promise to explain the relationship between the two men who fought at Gallipoli. Arthur’s father George 1844 was the son of Thomas 1807 and Mary nee Garner. Thomas’ brother Richard 1805 left Stanbridge, married Martha Walker and established a family in Soulbury, Bucks, members of which are still there. Richard’s grandson, William Francis, born Soulbury 1857, moved to Hatfield, near St Albans and married Sarah Kefford. Their son, John Henry Tearle 1887 died in Gallipoli in 1915. So John’s g-grandfather and Arthur’s grandfather were brothers. Read the story of Norman 1919 Soulbury to see the tragic deaths on the same day in WW2, of two other men with Soulbury (and therefore Richard and Martha) beginnings.

I have discovered the following statistics about WW1

74 family members joined the war effort.

14 were killed, including Louisa nee Lees.

Of the few hundred Tearles alive in the world in 1901, this is a very valiant answer to the call to arms. We certainly “did our bit” and our grandparents paid most dearly the price to keep our countries (at both ends of the world) free from the oppression an invading country would surely enforce.

Summary:

When Pat Field showed me the identity of Arthur Walter Tearle 1880 of St Pancras, as opposed to other Arthur Tearles I had confused him with, it came as a blinding shock of light. So many pieces fell into place all at once, especially around the very problematical families in the Willesden cell. I hope I have shown you the relationship between the members of that cell and hinted at the network that was operating – on a very informal and family-oriented way – to protect the family as it left Stanbridge and made its way, somewhat reluctantly, I think, given how slowly it developed, along the newly laid roads of the railway. In its early stages the, the railway was laid from Euston Station in London all the way to Preston in Lancashire. By 1848, there was even a branch line to Dunstable as close to Stanbridge as Stanbridgeford. It was built by none other than Robert Stephenson himself. A group left Leighton Buzzard for Preston in the 1850s led by Joseph 1838 and Sophia nee Kibble. Joseph’s brother George 1825 and Maria nee Franklin started the Yorkshire Tearles and George 1818 was the patriarch of the Watford cell which expanded even to Australia; and now we can see that George 1844 was responsible for setting up the Willesden cell. We can see now how easy it was for members of the group to come and go from Willesden – first stop, Euston, then Dunstable and on to Stanbridge.

The harrowing story of Arthur Walter and Ethel is at once part of the intense micro-world of individual families struggling to survive, but at the same time it also serves as a backdrop and even a model for the greater story of the Tearle family expansion.

This has been a difficult and very moving story to tell, but intensely satisfying in its conclusion.

Footnote:

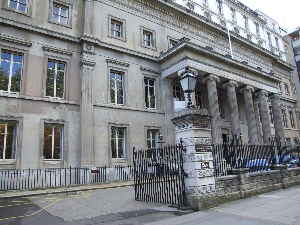

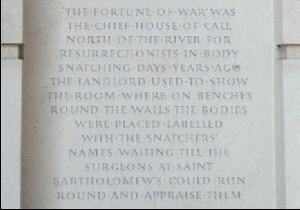

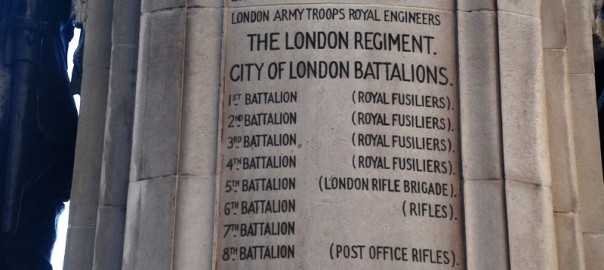

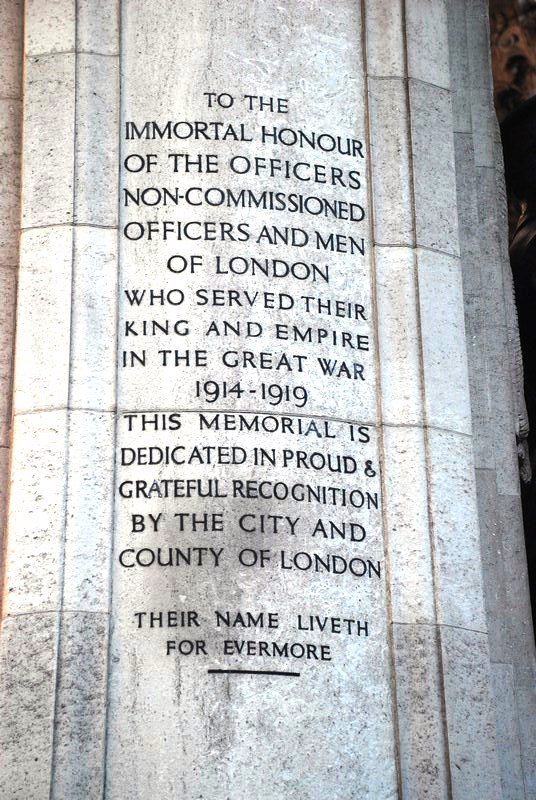

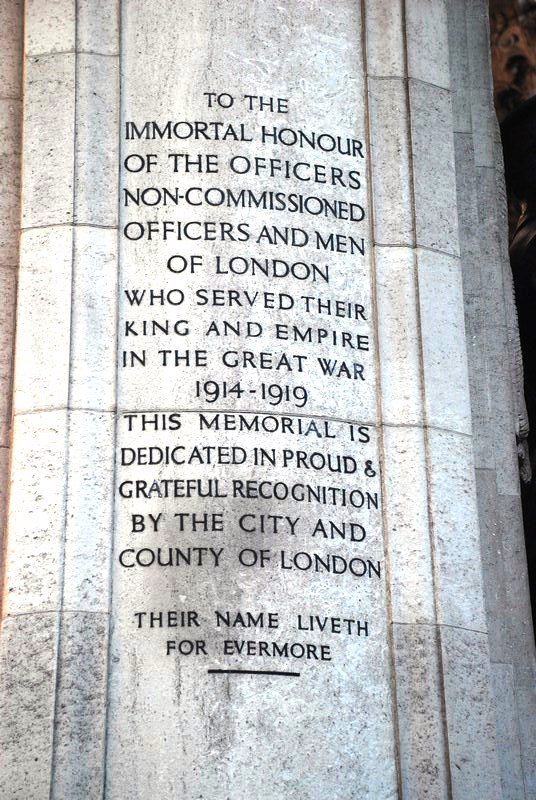

On a visit to London in Feb 2016, Elaine and I found the WW1 memorial to the men and women of London City and County who had fought in the Great War. It sits at the foot of the steps to the London Corn Exchange in Cornhill, across the road from the Bank of England.

WW1 Memorial, Cornhill

The dedication states that it is for all the battalions, rather than named casualties:

Dedication of Cornhill WW1 Memorial

The most important reason for showing it here, is that this memorial is all there is to remember that Arthur fought in WW1. On the back of the memorial is the battalion he fought with, even in Gallipoli – The London Regiment, (City of London) 3rd Battalion, the Royal Fusilliers:

The London Regiment, City of London Battlions, 3rd Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers, for Arthur Walter Tearle 1881, on the WW1 Memorial, Cornhill.

The agonising pain that Arthur suffered for the rest of his life will be remembered with this beautiful tribute to those who died, and those who lived in suffering, alongside him.