6 July 2001

Mr Jim Spence

Christchurch

NEW ZEALAND

Dear Jim

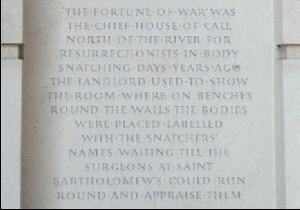

I have brought to England all the material about the Orange family that you sent me. A few weeks ago, I was browsing through it all and I realised that I had heard of Southwark and couldn’t think why. They ordained the latest Bishop of St Albans in Southwark Cathedral and while I was looking through your material I saw Helen Hinkley, 53 Union St, Southwark. Within weeks, I was called to a job interview at Sainsbury’s 169 Union St, Southwark and I spent the day, either side of that interview, wandering around the area that Helen would have known so well. In a week or so, I was appointed to a job with Sainsbury’s in Rennie St, just around the corner from Union St. I sent the following to Mum:

I have landed a very nice job as a Technical Support Analyst on the Help Desk for Sainsbury’s head office in Rennie House, Rennie St, Southwark. Pronounced SUTHic. The place is often confused with Suffolk because lots of Brits can’t say the th in Suthic, so it comes out suffok anyway and people say to me, “Oh, you’re working in Suffolk – that’s a long way from St Albans ….”

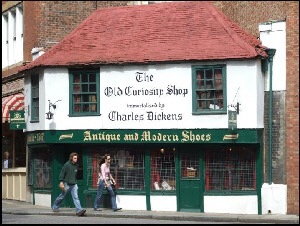

Now, Mum. Your grandmother, Elsie’s mum, Helen Orange, nee Hinkley (I’ll call her Helen Hinkley for the moment) was born in 1865 and lived at 53 Union St, Southwark. When she left for NZ in 1883, she left from a very good place to leave. It’s easy to picture the Dickensian pea-soup smogs and imagine peering through slit eyes as you pick your way to work through the grubby brick buildings, skipping past horse droppings, breathing the foul and putrid air and listening for the trains hissing and rattling noisily overhead, as they make their way to London Bridge or Blackfriars.

She was a nurse in London, did you know? I’d love to know if you ever met her – she died in 1928, and you would have been 7 at the time, and she divorced your grandfather in 1924, so it’s quite possible you never meet her. However – back to Southwark. I’ve taken to walking all around the Bankside area that Helen would have been familiar with and I have been looking for anything older than 1883, so that what I am looking at, she would have seen.

Well, there is a lot. Firstly, her house is still standing.

53 Union St – middle house was Helen Hinkley’s.

It’s just the shell and is being refurbished for business premises, but many of the houses around it are still in 1883 condition and you can easily get a sense of the dust, grime and poverty of the area. It was primarily a warehouse district and many of the Victorian era buildings still standing, although converted to modern use mostly as offices, have retained the lifting gear attached to the outside walls.

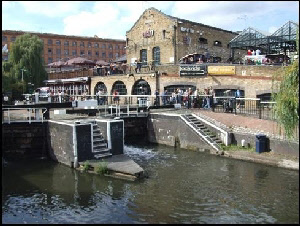

She would have been familiar with the Southwark Cathedral, which was called the Church of St Mary Overie when she lived there – it became a cathedral in 1910. It’s only a few streets away, adjacent to London Bridge.

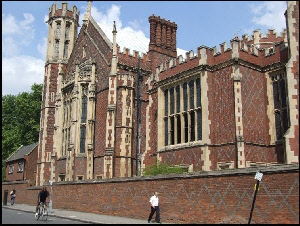

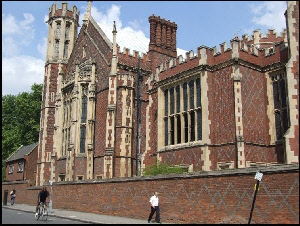

Southwark Cathedral

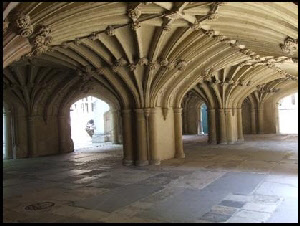

She would have been familiar with the stories of The Clink – the prison that gave all others the name. It’s just a few streets away, even though it wasn’t an active prison when she lived there, the rubble from a huge fire in the area in 1814 was still there in 1883 and its underground vaults still exist, too. It was the prison for the Duke of Winchester in Winchester Palace and it started life in the 1300’s. A really horrible place.

Entrance to the Clink.

Southwark has been home to prostitution and crime since Saxon times. The Duke of Winchester “regulated” the brothels and owned a large section of Bankside since King Steven gave it all to him in the 1130’s. The Clink was his private prison and he held life and death over its inmates until the prison was destroyed in 1780.

Prisoner in overhead cage outside the Clink.

There is a little bit of Winchester Palace still standing – a wall and a large rose window – and under that is the Clink. In Clink St, of course. The palace itself, in its heyday, was inside a fully-walled area of about 200 acres; all that’s left today is that bit of wall with the window, and the remnant of the Clink.

Winchester Palace, the last fragment.

She would also have been familiar with St Paul’s Cathedral towering over the Thames on the other side of the river, and all the other works of Sir Christopher Wren in the area built in the late 1600’s, early 1700’s.

St Pauls Cathedral

His chief mason, by the way, was a man called Edward Strong who was a citizen of St Albans and is buried here in St Peters Church. The Blackfriars bridge Helen crossed to get to The City from Bankside is the same one I cross to get to work, because it was built in the 1760’s; by an engineer called Rennie, incidentally. She would have been familiar with the Blackfriars rail bridge, too, that crosses the Thames and swings through Southwark on a big brick viaduct. I suspect that then the arches would have been open, but today they are bricked up for lockups – and there is a very large amount of space to be let under the arches of a rail bridge.

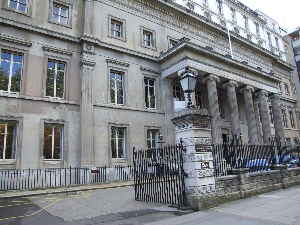

Ivor Adams, my cousin on my grandmother Sadie Tearle’s side, who has worked in The City most of his life, said that Bankside was the haunt of the Teddy Boys in the 1920’s and 1930’s and even today, in spite of all the upgrading that has been done there, areas just to the south, like Peckham, and Elephant & Castle, are still poverty-stricken and crime-ridden. If you stay close to the river, you’re ok. It’s very nice. I walked 7 minutes from work down The Thames Walk to the Tate Modern, a coal-fired electricity station that has been converted into the largest indoor space I have ever seen.

Tate Modern.

And they use all this space for an art museum. Free admission, too. I could only spend 10 minutes there but the building outside is massive in brick, dominated by a tall red-brick chimney that has been a feature of the Bankside skyline for nearly a century. Inside, it is light and airy and there are overhead cranes quietly tucked away waiting to move large and heavy exhibits.

I have attached photos of the landmarks in the Bankside area that Helen would have seen.

I have also found Glen Parva, Blaby, Leicester, where Albert Edward Orange (1865-1942) came from. It was a Roman settlement and nestles in a crook of the A426 and the Leicester Ring-road. There is a Great Glen in the area as well as Peating Parva, Ashby Parva and Wigston Parva. Elaine’s cousin, Jack Dalgleish, lives in Leicester and we have been to see his family several times. Would you like some photos of 1870’s Glen Parva? Next time we go to Leicester we’ll stop and have a look to see what is left. Do you have a street name? That would be a real help.

Kindest regards

Ewart Tearle