The origin of the Sutton, Surrey Tearles

By Ewart F Tearle

Barbara Tearle, Rosemary Tearle of Auckland and Pat Field started the research into the story of George and Elizabeth in 2005. Rosemary’s husband, Michael Tearle, is a Sutton, Surrey native. The years of research were concluded in 2014.

It is quite difficult to piece all the bits of this story together, mostly due to the lack of records, and some families not baptising their children. Many families have to be stitched together from the stories of others in Tearle Valley.

The Stanbridge Parish Records (PRs) record the birth on 29 June 1770 of John Tearle, son of John Tearle 1741 and Martha nee Archer. John 1741 was one of the sons of Thomas 1709 and Mary nee Sibley. He heads one of the founding branches of the Tearle Tree. It is also the largest and when I have printed it for TearleMeets, the unrolled sheets stretch along the floor of Stanbridge Church from the altar to the vestry.

The Tilsworth PRs record the marriage of John Tearle of Stanbridge to Mary Janes on 14 January 1792.

In the Stanbridge PRs John and Mary Tarle/Tearle were baptising children from 1794 to 1817. Their first child, though, was Thomas 1792, born in Ivinghoe Aston, Buckinghamshire.

He was registered in the Ivinghoe PRs; 8 October 1792, Thomas, son of John Tale and Mary. All of their other children were born in Stanbridge, including Gene (Jane?) in 1807, who married Jonas Gates, Elizabeth born 1810, who married George Tearle, and Ruth born in 1813, who married George Gates.

Here is a note on the Tilsworth Church building and another note on its history

John Tearle, Carpenter, 70 years old, is in the 1841 census, married to Mary Tearle. He does not make it to the 1851 census, but Mary does. Here, she is recorded as a widow, 79 years old, on parish relief and she is a carpenter’s wife. She came originally from Ivinghoe Aston, Bucks. At 79 years old, she was born in 1772. This is proof positive that her maiden name was Janes. I am not sure why her daughter Elizabeth 1833 says in the Wesleyan Methodist circuit baptisms that her mother was Mary Tearle, rather than Mary nee Janes, but she may simply have misinterpreted the question.

These records are capable of making mistakes. For instance, in the Dunstable Circuit Methodist Baptisms are these two girls, baptised on the same day, and recorded with the wrong father’s name, because Annie Eastment married Charles Tearle, not John Tearle.

| 27 Oct 1870 | 23 Nov 1870 | Laura Ellen | John & Ann | Dunstable | Should be Charles & Ann | Dunstable Circuit |

| 17 Nov 1866 | 23 Nov 1870 | Sisera Eastment | John & Ann | Dunstable | Should be Sylvia to Charles & Ann | Dunstable Circuit |

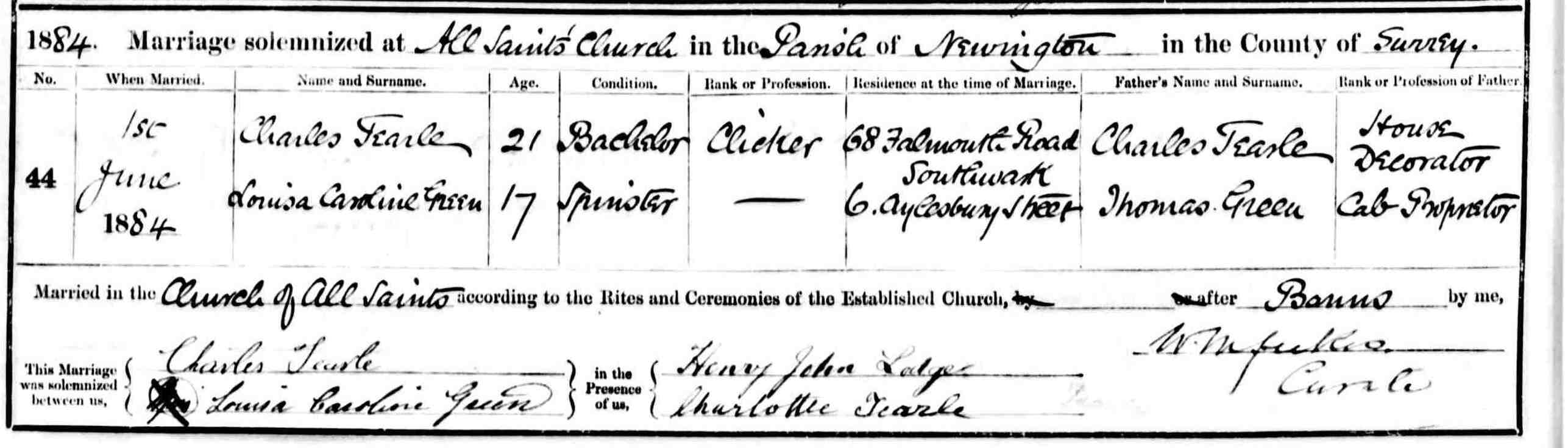

Charles 1836 was a son of George 1810 and Elizabeth 1810; he married Annie Eastment. He was a brother of James Tearle 1834 who founded the Sutton, Surrey Tearles. Subsequent children were recorded correctly.

Here is the full list of the children of John 1770 and Mary nee Janes, all of whom, from Richard 1794 onwards are recorded in the Stanbridge PRs:

Thomas 1792 Richard 1794

Ann 1796 Sarah 1800

Susan 1802 Mary 1803

Jane 1807 Elizabeth 1810

Ruth 1813 Jabez 1817

Now that we know who the bride is, it is time to have a look at George 1810, her second cousin.

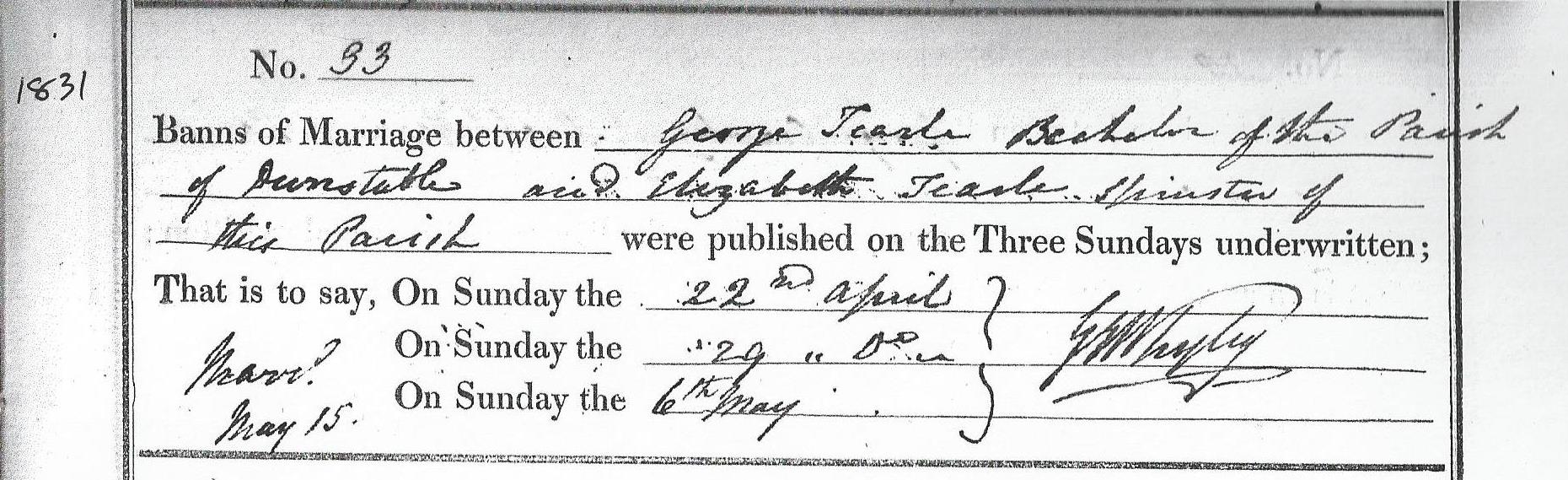

The Stanbridge banns register notes that the banns for George and Elizabeth were read to the Stanbridge church congregation on 22 April 1831, 29 April and 6 May. In the margin, is the note “Married May 15”, so I think that means they actually were married in St John the Baptist, Stanbridge. The entry also says that George was “of Dunstable” but that does not mean George was born in Dunstable, just that he was living there at the time.

Their first child, a daughter, Elizabeth, born in Dunstable in 1833, was baptised in the Wesleyan Methodist church in Dunstable, in 1833, and Elizabeth 1810 was recorded as the daughter of John and Mary Tearle. The two witnesses at George and Elizabeth’s wedding were George and Ruth Gates. They were Methodists too, and baptised their children at the Leighton Buzzard Methodist church. There were two Gates couples, George and Ruth, and Jonas and Jane. The Leighton Buzzard Methodist baptisms of both couple’s children report that Ruth and Jane were the daughters of John and Mary Tearle. The question is – which Mary Tearle?

Sometimes the data that links families takes a long time to arrive. For instance, Charlotte Tearle 1808 of unknown origins is found in the 1851 census in service – she is 43 years old and from Tebworth, Bedfordshire. In 1858 she marries James Smith and says her father is Richard Tearle, labourer. Now we know who she is – a daughter of Richard Tearle of Tebworth, he had two wives – Mary Pestel and Ann Willis. Charlotte is the daughter of Richard and Mary nee Pestel.

Firstly a note about Chalgrave. This little parish consists of a village, a civil parish and two nearby hamlets – Tebworth and Wingrave. English custom has it that any assemblage of houses (no matter how large) without a church is a hamlet, and any rural grouping of dwellings (no matter how small) with a church is a village. We are referring to a Church of England church, of course, also known as the Established Church. If you walk from Stanbridge down the hill to Tilsworth (about 200 yards) you’ll see just how small a village can be.

In official documents a person may be shown to be from Tebworth, or Tebworth, Chalgrave. In the first instance, the reference is to the hamlet, and the second reference is to the hamlet and parish. The same applies to Wingrave. A reference to Chalgrave may or may not infer its village. However it may be, you can rest assured that any reference to Chalgrave is to enclose only a few hundred acres of land.

To return to Richard 1778, we note that he is a son of Joseph Tearle 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp. Joseph was the first son of Thomas Tearle and Mary nee Sibley, so Richard is one of Thomas’ grandsons. His baptism is recorded in the Stanbridge PRs: Baptism: 1 Nov 1778 Richard, son of Joseph and Phoeby.

Phoebe nee Capp, his mother, was an ardent follower of Methodism, and that allegiance followed her family for many generations. Some of the early Tearles baptised their children in the Dunstable Circuit, mostly at the rather imposing Wesleyan chapel in The Square, Dunstable.

In the Chalgrave Baptisms, there are only five Tearle entries:

5 May 1805 Mary dau Thomas and Mary Tale (unknown)

1 Nov 1812 Pheebe, dau George and Betty Tale (daughter of George 1785 and Elizabeth nee Willison. Died 1837 in Leighton Buzzard)

31 July 1814 William, son Richard and Mary Tail, Tebworth, Labourer (married Hannah Pratt in 1838)

25 July 1816 Thomas, son Richard and Mary Tail, Tebworth, Labourer (married Ann Jones in 1840)

24 June 1818 Mary, dau Richard and Mary Tail, Tebworth, Labourer (married Richard Fensome in 1843)

The Tearle Deaths list is even shorter:

24 June 1818 Mary Tail 39 years (Mary nee Pestel, wife of Richard 1778)

1 April 1820 Thomas Tail, 39 years (unknown)

It is a very telling entry; Mary Tail, the mother, died on the same day her daughter was baptised. This should close the book on the children of Richard 1778 and Mary nee Pestel, but it does not. Over several years we found Chalgrave “strays” – people born between 1803 and 1818 who said they were from Chalgrave.

To complicate things a little, there was another couple in Chalgrave parish who were having children: George Tearle 1785, from Stanbridge, and his wife Elizabeth (Betty) nee Willison. They married in Toddington on 6 October 1811, and their first child, Phoebe, was born in Chalgrave on 1 November 1812, as you can see above. George 1785 was a son of Joseph 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp, so he was a younger brother of Richard 1778, and cousin to John 1770.

The children of George 1785 and Elizabeth nee Willison (Betty) were:

Phoebe 1 Nov 1812 Thomas 09 Apr 1815

John 20 July 1819 George 09 Jun 1823

Ann 27 Mar 1826 Joseph 30 Apr 1829

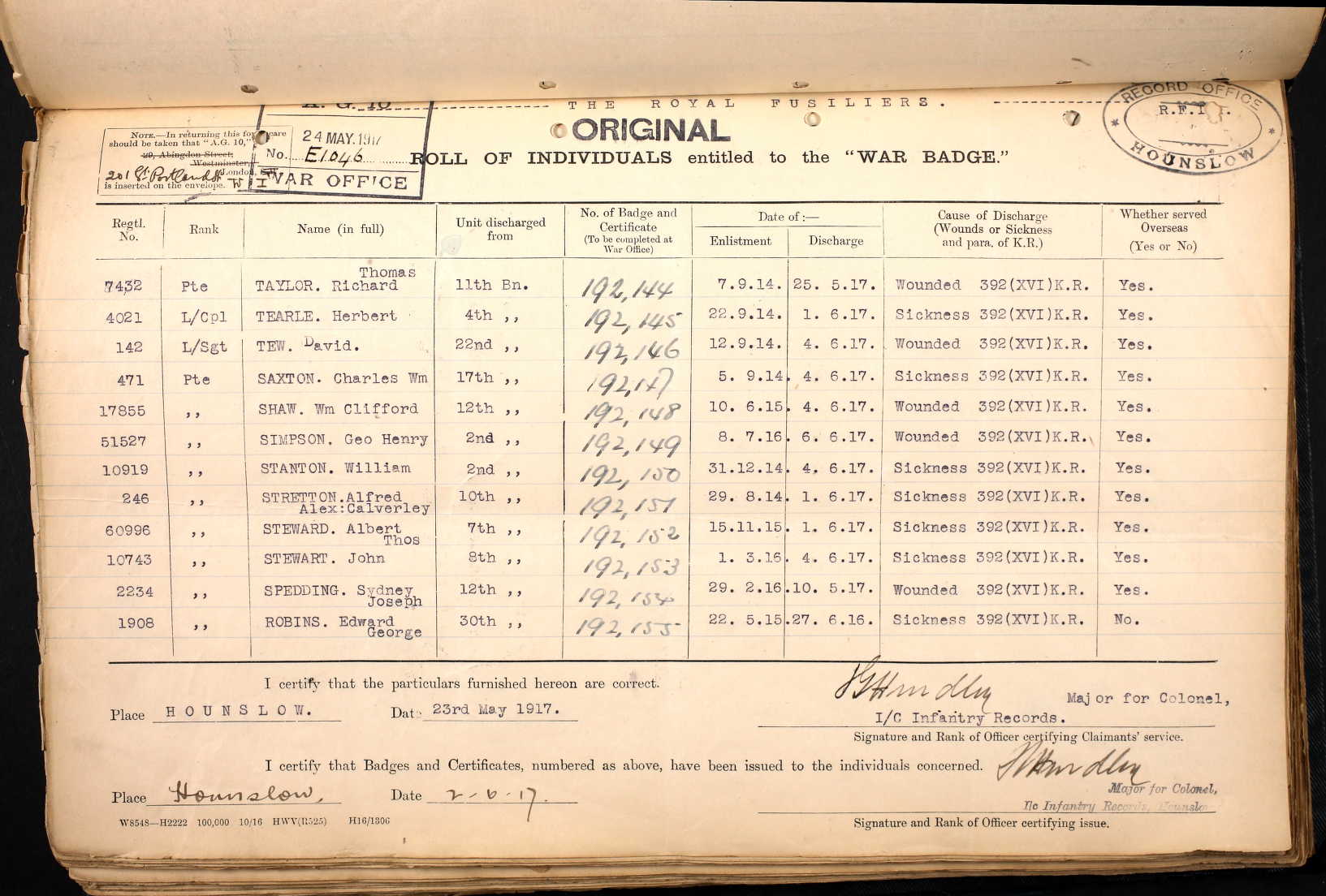

George 1823 was a successful businessman and merchant. He married Sophia Underwood, daughter of a wealthy and influential Luton business family. Their grandson, Ronald William Tearle 1897, was killed in 1917 and is buried in the Huts Cemetery in Dikkebus, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. He is also remembered on the War Memorial outside the council offices in Luton.

Joseph 1829 was a straw bonnet maker in Bedford, and married Carolyn Haydon in Luton in 1854. One of their sons, Joseph Sydney Tearle, was baptised on the Luton Methodist circuit (probably in Chapel St) in 1861. He emigrated to Australia and died in Cooktown, Queensland in 1886, unmarried.

Apart from George 1823 and Joseph 1829, the children of George and Betty did not marry, and some died very young.

The reason I have covered the Tearle births above is because, having assured ourselves of the parentage of the Tearle children listed, and taken a lesson from the story of Charlotte that there were some undocumented children, we might be able (with Barbara’s help) to give a home to the other Chalgrave strays:

Joseph 1804 James 1806 George 1810

Joseph is the first. There is an extensive essay on the origin of the Preston Tearles and in that essay, we looked for Joseph’s parents. Richard and Mary nee Pestel looked the most likely couple because their first child was Phoebe 1803, then no more children until William 1814. Joseph’s death certificate of 1889 in Preston, said he was 90 years old, which took us back to 1799. We checked the 1841 census, and at that time both he and his wife Mary Ann nee Smith were 35 years old, so that meant 1806. As a group we settled on 1804, two years after the birth of his elder sister. We checked the 1851 census, where Joseph was boarding with his son, George 1825. Joseph was male, father, 48 years old, and crucially, he was from Tebworth. In the early 1800s George and Betty had not started their family, and only Richard and Mary nee Pestel were having children in Tebworth – starting with Phoebe. Joseph 1804 of Tebworth looked very comfortable in this family.

Next was James Tearle and Mary nee Webb. I was contacted by the gg grand-daughter of James and Mary, who considered that it was most likely that Richard and Mary nee Pestel were James’ parents: the first son was called Richard, and one of the girls was Phoebe. In the 1841 census, James and Mary were living in Dunstable with seven children. In the 1851 Dunstable census, James reported he was from Tebworth while Mary was from Little Brickhill, where they were married on 17 March 1825. Both James and Mary were 35 years old, so that made James born in 1806. We fitted him in between Joseph and Charlotte, and he looked quite at home there.

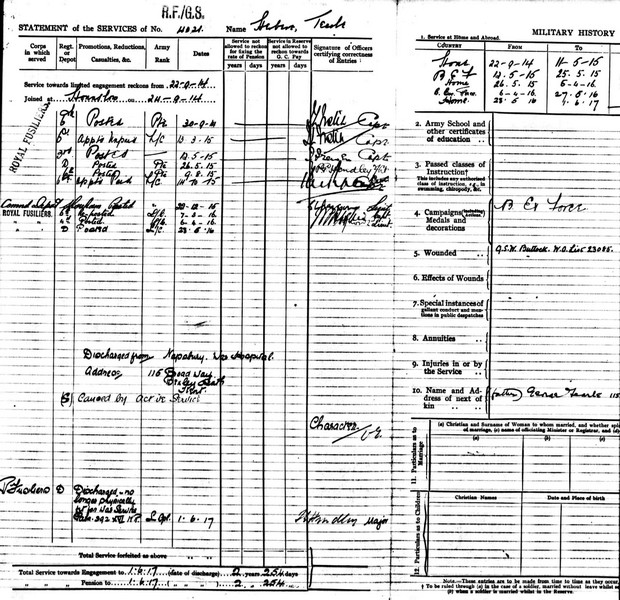

The last stray was George, who had married Elizabeth Tearle 1810 in Stanbridge on 15 May 1832. They had three children, so we tried the children’s name test. Elizabeth was named after her mother, and James 1834 was probably named after James 1806, above. Quite why they called the last boy Charles is anyone’s guess, but two out of three will do. We checked the 1841 census, and George said he was thirty, making his birthdate 1811. The early census birth-dates are more reliable because the numbers are smaller, and more likely to be closer to the actual birth date than later censuses. The 1851 census was enlightening in other ways: George was 41 (born 1810) a Post Boy who carried mail from town to town and he was from Wingfield. This means he was from Chalgrave parish. His death certificate said he was a groom, 80 years old and living in Dunstable. Details were supplied by Elizabeth Tearle Fensome (George’s daughter had married Charles Fensome in 1863) who was present at the death of her father. The 1810 date for his birth fits very nicely in the dates between Charlotte 1808 and William 1814.

There is just one final thing to do, and that is to explain how Richard 1778 had one more child – apparently after his wife Mary Pestel had died. John Tearle 1823 was baptised at Chalgrave on 27 April 1823, son of Richard and Ann. The writing is difficult, but it says Ann, and certainly does not say Mary. In the Chalgrave PRs, Richard married Ann Willis on 24 January 1822.

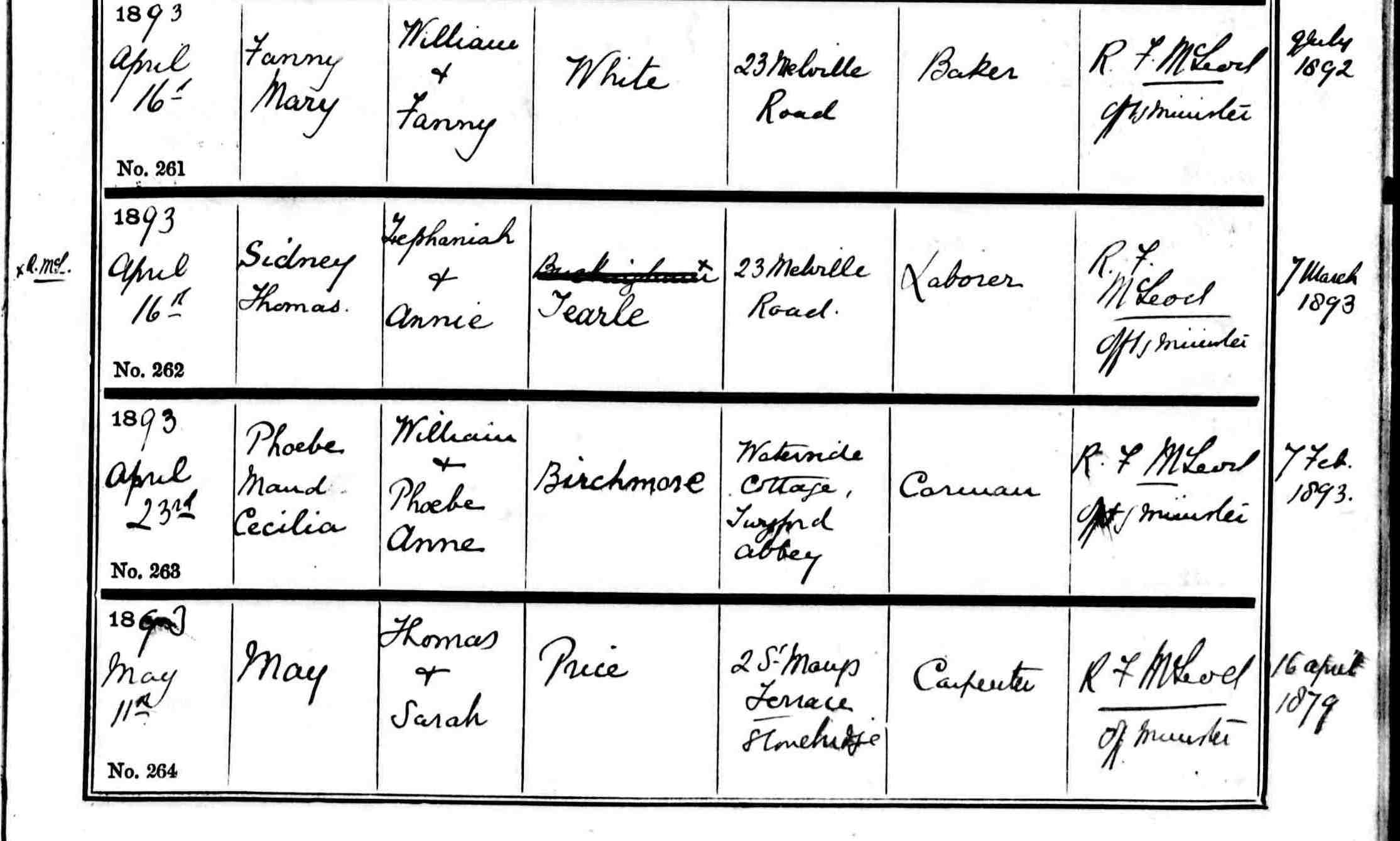

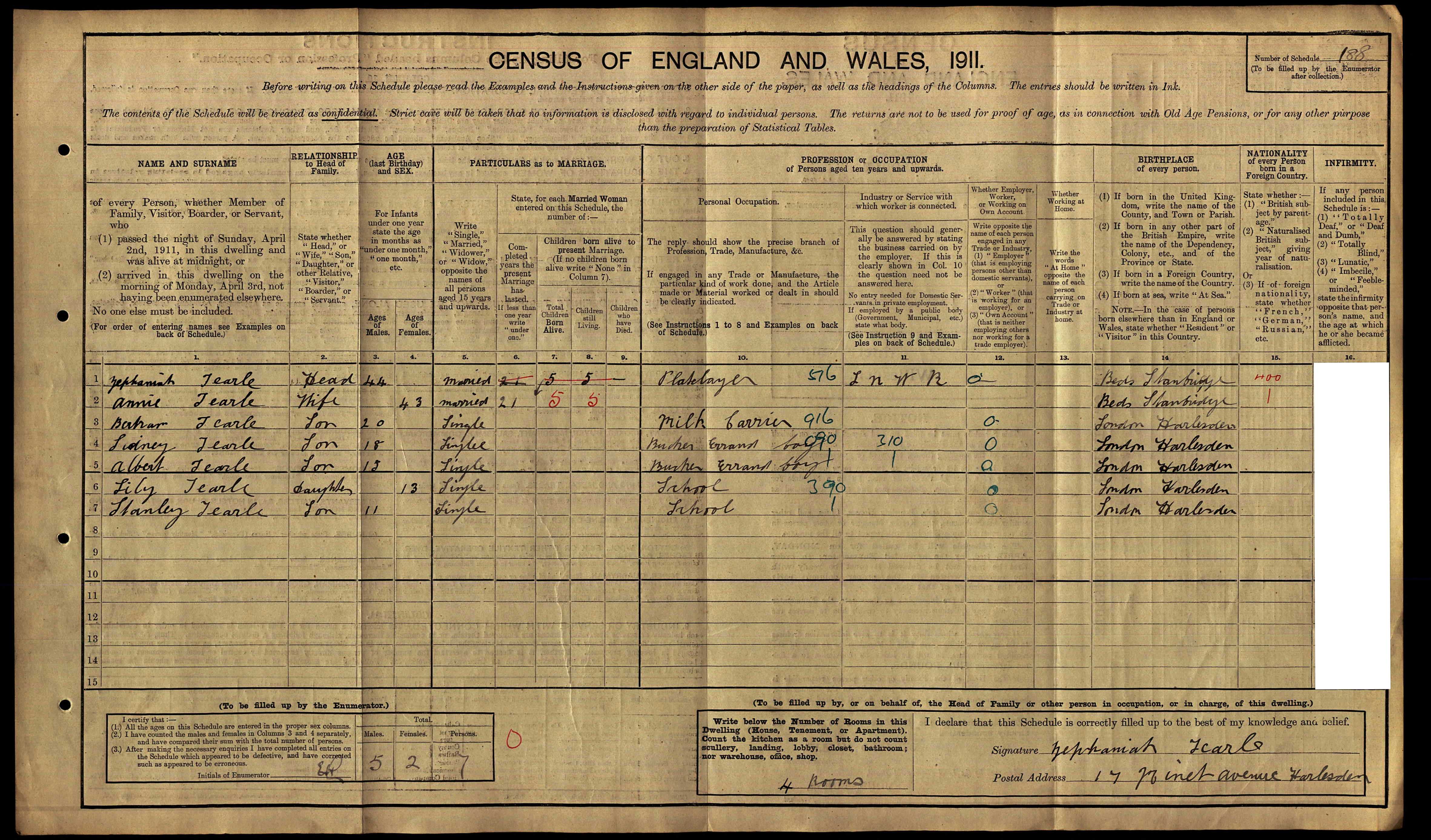

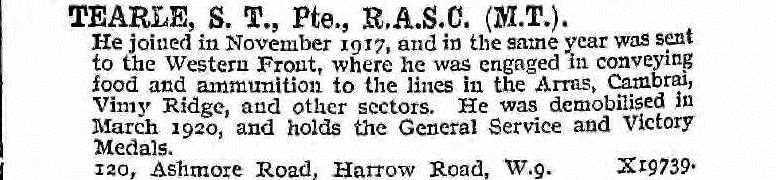

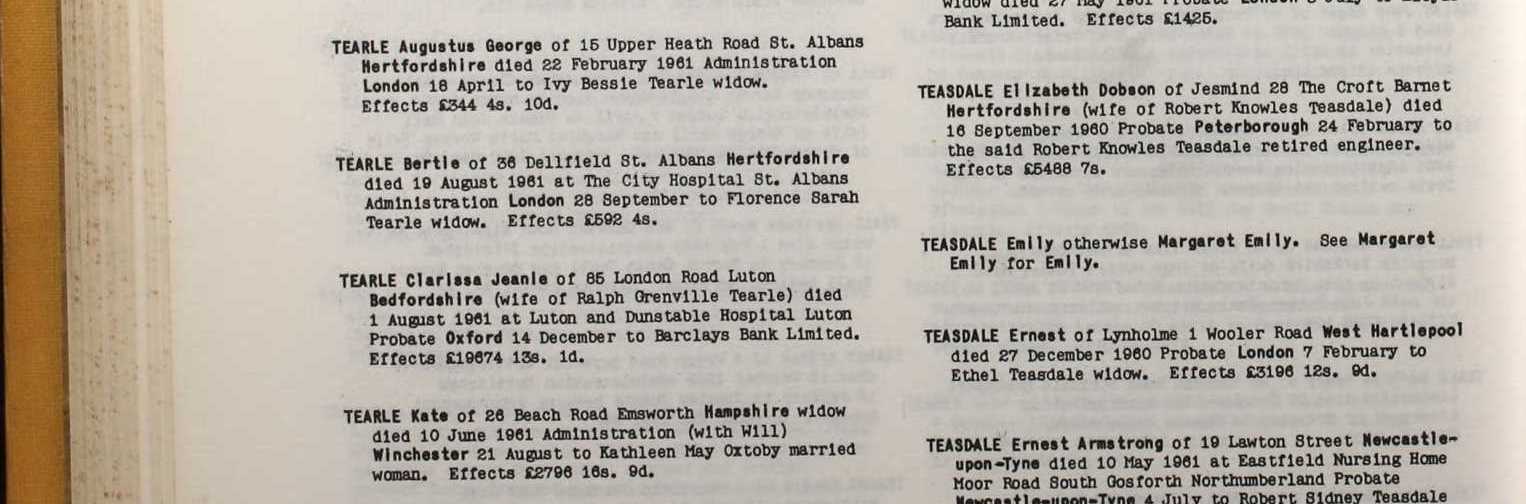

The postscript to this story is that George and Elizabeth’s son, James 1834 of Dunstable most likely left the town from Dunstable Church St station on the Great Northern Railway – third class, no doubt – and arrived in Euston Station on the same day. Nothing could be further from his forbears than this. It was like flying to the moon, but the landing was real – he was in London. On the 5th of May 1860 he married a Berkshire girl in Islington, Sarah Ann Jones. They had four children in Holloway, Islington then left for Sutton, Surrey, where John Thomas Tearle was born in 1871. He was followed by Laura Ellen in 1873 and Henry Arthur in 1875. James died on the second of July, 1876, only 43 years old. His legacy, though, lives on. The era of the Sutton, Surrey Tearles had started.