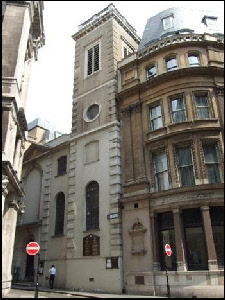

I’ve been wondering for a while why there is a Fleet Street sign on the Old Bank of England building, but a there’s a Strand sign on the end of the Royal Courts of Justice, just 20m apart. Somewhere between the two, on a straight piece of road, Fleet St changes its name. I found the reason yesterday; did you notice the Victorian needle monument in the middle of the road, with Queen Victoria and Albert on the base and a griffin on the top? Underneath the griffin, if you walk around the monument, you can read “Temple Bar formerly stood here.”

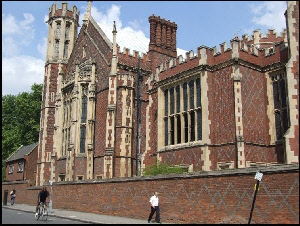

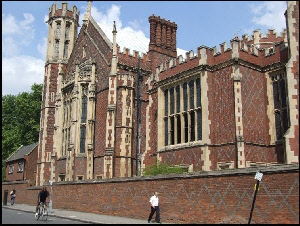

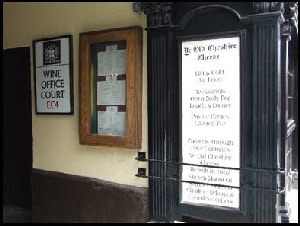

It was one of the gates to London City – along with Ludgate, Moorgate, Newgate, Aldgate, Cripplegate, Aldersgate, and a couple of others I can’t remember now. The Victorians pulled it down because it was causing traffic jams, but they put a monument in its place because Temple Bar has royal significance. It was reassembled as a grand entrance for the beer baron Sir Henry Meux in Cheshunt, Herts. His wife was a banjo-playing woman often accused of being posh above her humble origins. I often wonder if she was the original Lady Muck. The City of London rediscovered the gate, brought it home, set it up and reopened it in 2004. This is the view you would have seen from the Strand as you were about to enter the City.

Walk down Newgate Street from Holborn Viaduct and near the end turn right into Rose alley, which empties into Paternoster Square. Walk past the London Stock Exchange, through the archway to St Pauls and then look behind you. That is Temple Bar. I think the room at the top was the gate house.

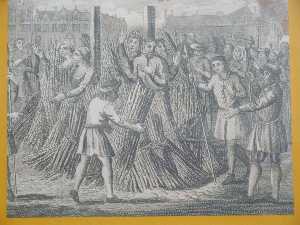

Word has it that it was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and it is the only surviving gate to the City. The City fathers used to stick the heads of executed prisoners from Newgate prison on spikes over its top, but the custom died out in the 1750s.

Here are the two statues on Temple Bar that you can see as you walk into Paternoster Square from St Pauls Cathedral of Charles I and Charles II. These are the restored originals by John Bushnell.

Below is the monument the Victorians left behind in Fleet St to mark where Temple Bar used to stand. You can see Queen Victoria looking out on this side of the monument, and beneath her is the ironwork below; an incredibly detailed relief showing the queen processing to the Opening of Parliament and all the excitement it caused.

On the side of the Fleet St monument that faces the Royal Courts of Justice is a statue of Prince Albert and beneath him is the bas relief below, showing Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on their way to St Pauls. The Royals would have processed from Buckingham Palace down the Strand, so they would have passed through Temple Bar then along Fleet St and up Ludgate Hill to ascend the front steps of St Pauls.

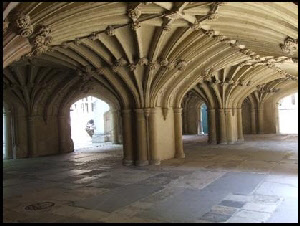

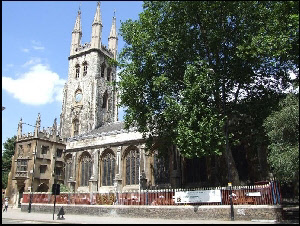

The bar may originally have been no more that a chain across the road and got its name from being immediately outside The Temple, and Temple Church. It was never sited on the line of the Roman wall, so it did not accurately mark the boundary, but you had to pass through it to enter the City

If you go to the Lord Mayor’s Show and stand somewhere near St Paul’s you will see an ancient ritual where the mayor presents his sword to the Queen, or her representative, and she formally hands it back. This practice used to happen at Temple Bar, in which the mayor, on the City side of the bar, would hand over his sword as a sign of loyalty.

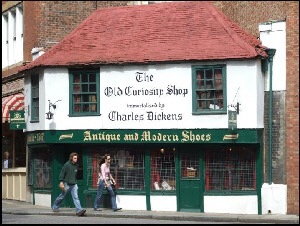

While we are talking about the Old Bank of England building in Fleet St, as I did in the first paragraph above, did you know that Sweeney Todd “The demon barber of Fleet St” had his barber and surgeon shop on one side, murdered and butchered his victims in the vaults underneath; and gave the meat to be used in pies sold by his mistress, on the other side?