Prague was mentioned twice within a couple of months. The Metro newspaper travel section told me it was one of the rising destinations in the old Eastern Bloc and then Jill Adams came back from the Continent delighted with her visit to Prague. “You’ve got to go!” she said, “It’s beautiful, and so unspoiled.”

Genevieve said “Try the Continental trains, so that you can use your plane ticket more efficiently. They’re really cheap, but go first class, and visit a couple of other cities as well.” I spent a frustrating week trying to put together three Continental cities for the three weeks of Elaine’s summer break. The plan was to fly to Prague and then take the train to…. I couldn’t get any train tickets on the internet.

We went to the Marshalswick travel agent again. He could get the train tickets all right, so how would we like to fly Prague, take the train to Vienna, then the train again to Budapest and then the plane home? Lovely cities. We’d get our tickets in a week, and leave from Heathrow Terminal One. Yes? Excellent.

The plane for Prague left Heathrow at 07:00, that meant we had to be at the airport at 05:00, which meant we had to catch the Picadilly Line from Kings Cross at 03:30. That was not good news; the Tube is closed from 01:00 to 05:00. We elected to stay at the airport overnight, so on the day, once I had arrived home, we finished packing and took the Thameslink train to Kings Cross, the Picadilly Line to Heathrow, being careful to get off at Terminal One, and looked around to see what we could do from midnight until 05:00. There was depressingly little. A walk around the terminal, poking into every corner, took five minutes, and twice round took ten minutes. It was clear there was no point in trying to while away the time by walking around the terminal. We went upstairs to Costa and glumly looked at each other while we slowly sucked on cardboard mugs of frothy cappuccino.

“This is going to be a long night,” said Elaine.

It’s true to say the night ended, but rest assured that when we looked out of the plane and saw Prague lying in the sunshine and we were wheeling down to land, we felt a lot better.

“Prague is not in Eastern Europe, and neither is the Czech Republic,” said the chaperone in the big grey 4×4 that picked us up from the airport, “it’s at the very heart of Central Europe. People often think that because we were a Soviet buffer state we must be Eastern, but we are not. Geographically and historically we are truly European. Our famous sons are Franz Kafka, Jan Hus, King Wenceslas and Alexander Dubcek. Johannes Keppler came here to study and to teach. We are civilised in the European traditions and we have a complex history of Catholicism and Protestantism, much like any other European country.

Across Staromestske Square to Tynsky’s Cathedral

Soon we will be part of the European Union. Last year, Prague was hit with a devastating flood from its own river, the Vltava, and you will see much work to fix the damage and much more work to add to the city’s charm while those repairs are going on.” The 4×4 left us at the Quality Hotel on the edge of town so we dropped off our bags and went back onto the street.

Below us was a deep blue river with a weir off to our left and all around us were building repairs. In the middle of the road alongside the hotel, workmen and small front-end loaders were laying tram tracks in a deep concrete-lined ditch. We turned right and followed the road a couple of blocks until we came to a T-section with a wide road. If we went left, it looked like the road disappeared into a slum, but since all the road signs – none of which we could read – pointed to our right we went that way.

Building repairs

The scene outside our hotel was replicated here; they were laying more tram tracks in another concrete ditch in the middle of this road, too. We picked our way through the rubble of the repairs to the footpath and watched a workman with a pneumatic chisel noisily peeling plaster off a brick wall. The flood line was clearly above his head, yet we were quite a way above the river. We called into a mini-market to check shop prices for essential items like soft drinks and bottled water. They are almost always a quarter of the price of buying water or lemonade at the hotel or in a café. We selected a 1L bottle of water and some delicious-looking pasties for a late lunch and walked over to the counter.

High water mark, Prague flood

The shopkeeper was a sunburned, greying, middle-aged woman with a green shop pinafore over a cotton floral dress and she couldn’t speak English, but she gave us a shy smile as we placed our purchases on the counter and offered her a note of local currency. She took our money and carefully counted back to us some more notes and some coins. We were charmed.

Outside, we checked the notes and coins and she was absolutely correct. We had taken a note of the prices and tried to fix in our minds where the shop was so we could get back to it from the hotel. While we ate the pasties and drank the water, we followed the road into the outskirts of town and watched the trams running on their old tracks, poked around a nice little outside market where I got some walk shorts and sunglasses, and admired a statue of construction men at work, left over from Communist days.

Construction men at work

The following morning, the 8th of August, after a delicious breakfast of fruit, cornflakes and bacon and eggs – no cheapie Continental breakfasts here – we asked the young lady at the hotel reception if she had a map of Prague. She did and it was free. We stood outside and examined the map. If we followed the river, it might be the long way round, but it would lead us past some bridges, an island and eventually into the middle of town. It was a perfectly beautiful morning and a walk would be good.

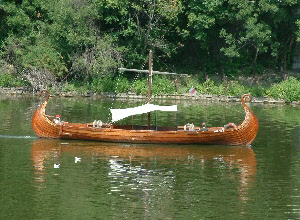

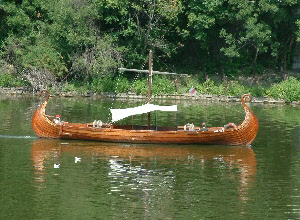

We followed the wide sweep of the river past the weir, past the island with a green domed building on it, past the stolid, glowering Education Department building with its guard sitting in an elderly red and white caravan just inside the barrier arm, past a water trike driven by two girls, past a quite magnificent blue and white river excursion steamer and we were in turn passed by all kinds of river craft – a replica Viking longboat, a little blue and white river boat with about thirty people lounging in deck chairs on its upper deck, and I said to Elaine,

“What’s he going to do when he gets to the weir? Jump it?”

And then we stopped alongside a bridge. “This is the Vltava River,” I said, checking the map. “What is that?”

Replica Viking longboat

In the background of the photo on the left is a tall black building, probably a church. What’s it all about? The map was silent. The girls in the river trike pedalled past. They were pedalling up river and they were hot.

I could smell coffee and I thought I could hear water cascading.

Behind us was a hedge and beyond that were a couple of little stalls, one with paintings and the other with a coffee urn boiling away. While we examined the paintings and drank our coffee, a fountain gurgled and two men sat in its edge with their feet cooling in the pool. There were several paintings of the scene I had just photographed. “What’s that?” I asked the chap with the paintings. I pointed at the painting of the bridge and the big black church and he just shrugged at me. I pulled out the map and tried again. “Up on the hill there, can you tell me what it’s called?” He shook his head, “catidralsanvita,” I think he said. “Thank you,” I replied.

Manesuv Bridge with Prague Castle behind.

I looked at the map again. The bridge was either off the map or it was the Manesuv. If the latter were true, then the very fine building to the left of the square immediately in front of us must be the Rudolfinum. Tall flags on the building confirmed my guess. I looked up our Lonely Planet “Prague” guide but I couldn’t find out what the Rudolfinum did. It didn’t help us to name the black church, either, but we would worry about that later. Another look at the map told us that the nearest sight was the Old New Synagogue in an area called Josefov. The Lonely Planet advised us not to miss it, this used to be the Jewish quarter and a wander around Josefov would be very instructive.

Manesuv Bridge and Rudolfinum

This little fellow caught our attention. We saw several of him, although none more of this size or this colour. At the Old Synagogue, we called into the gift shop and museum and Elaine asked who this chap is.

“Golem, his name is Golem,” said the young lady behind the glass counter.

Elaine picked up a stone miniature and examined the squat figure held together with straps and bolts.

“What does he do?”

“Originally, he was a character developed by Rabbi Loew to try to stop the locals from persecuting the Jews.”

“Why is he held together with straps?”

“Because he is made of clay, which cracks as it dries. The good rabbi broke up his creation in the loft of the Old New Synagogue when he decided Golem had accomplished his mission.

He’s now a Jewish children’s story character, not always very well behaved, but we use him to illustrate how good children should act. Sometimes he’s very funny.”

Golem

Elaine bought the miniature and a book of Golem stories to read to her class. “That’s lovely,” she said, “a little piece of real Prague to take back to my kids. They’ll find out about different cultures.”

We went up through the doorway of the old surgery building and past the Old Cemetery with its big trees casting a solemn gloom onto moss-covered headstones. The Old New Synagogue cost too much to go into so we gave it a miss.

“If we go back towards the river and then down a bit, we can cross the Charles Bridge,” I said to Elaine.

“What Charles Bridge?”

Old Jewish surgery, Josefov

“The next one along from the one we didn’t cross to get here.” I looked up the Lonely Planet. “The Judith Bridge was washed away in a storm and Charles IV built this one in the 1300s. Looks like the flood last year wasn’t the first. We didn’t see the bridge earlier today because of the bend in the river – or because we didn’t look.

The picture on the map showed an outline bridge of towers and bumps and it looked pretty impressive. The Lonely Planet said not to miss the buskers.

It was worth the walk. The bridge was crowded with people and there was no traffic. A large, dark brownstone church (St Francisl) covered the approach to the bridge on our right and dozens of people sat around the statue of King Charles IV taking in the last of the late afternoon sun. Grimly utilitarian five storey buildings glared down at us from our left, but the gothic tower that stood astride the bridge itself was a wonder in stone and lead. It was magnificent. Look how there’s more of the tower on one side of the bridge than the other, look at the arch; it’s like a cathedral window. Look at the roofline.

Tower, Charles Bridge

We couldn’t miss the buskers. There was someone every twenty feet or so, if not a busker then an artist, or a stall selling some kind of old rubbish. One group of buskers was particularly interesting because of the type of instruments they were playing.

Buskers, Charles Bridge

Opposite us was an arcaded walkway with lots of little cafes and shops selling toys and arty knick-knacks. “Dinner,” said Elaine with some conviction. “There will be something to eat here.” We wanted genuine Prague food so we looked for the locals. A little café had lots of dishes with dumplings – a Prague favourite – and the waiters were definitely locals. We sat at a green and white checked tablecloth and Elaine ordered a beef dumpling stew while I ordered the pork knuckle.

I got a shock when it turned up. It was about the size of my head and it was covered in golden crackling with a pickled gherkin and some tomato slices, served on a thick wooden plate. Someone had thoughtfully stuck a serrated knife into the joint. Elaine laughed “You are going to have fun finishing that!” I took a photo of it. It was unbelievable. The whole thing cost about four euros. I did finish it but not without people who were walking past stopping and staring at this skinny chap and his huge pork knuckle. About four couples stopped and ordered their own. Elaine had a ball laughing and gesturing. No-one understood a word anyone said but that’s the whole point of being in a foreign country. The language of food is universal, what need we for words?

On the way home, we stopped on Charles Bridge to admire a talented busker and his wonderful array of Central European instruments.

Musician, Charles Bridge

The following morning we had the usual delicious breakfast of cornflakes, fruit and bacon & eggs with toast while we chatted to a pretty young girl and her husband about Prague. They had spent all yesterday in town and were going back again today.

They had also been up to Prague Castle. “Is that it up on the hill?” I asked them.

The husband leaned forward in his khaki shirt and Cargo slacks. “Yes. Across Charles Bridge and up the hill; St Vita’s Cathedral is in the middle of the parade ground inside the castle. You get a wonderful view of Prague from up there.” When they had gone, we took a look at the map. It wasn’t too far, we’d walk there and drop into town on the way back.

Prague trams on the way to town

The morning was absolutely beautiful and it was a pleasure walking the couple of miles or so past the newly laid tram lines and the little outdoor market, crossing the Charles Bridge and walking up the hill to Prague Castle.

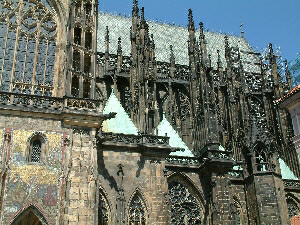

There wasn’t much of the castle to see, most of it was a maze of thick walls with battlements and a military centre tucked into a corner. Three self-conscious soldiers in blue parade uniforms with rifles at ease strutted from somewhere near the military centre across the parade ground to the castle gate and relieved the watch, who strutted just as self-consciously back. We joined a tour of the cathedral and admired its 12th century tomb with the effigy carved beautifully in marble on the top, and looked closely at the intricate work in the tall stained-glass windows. The cathedral was started by Charles 1V in the 1300’s so the tomb must have been brought there from somewhere else. There doesn’t seem to have been a terminal date applied by the builder because the cathedral wasn’t finished until 1929, when the last pieces of coloured glass were inserted into the windows we had been admiring.

I tried to take a picture of them while Elaine bought their CD, but people just kept walking into the frame. I must have tried six or seven times. Eventually, I noticed that if I went down on one knee to take the photograph, people would realise just in time what I was doing and they would hesitate for a moment and I could take the picture. You can see I’ve still got someone’s shadow in there, but I suppose that’s ok on a crowded bridge.

We continued walking across the bridge, dodging the stall-holders bawling at us and admiring the stone and bronze statues. There was even one of St Francis, patron saint of travellers.

On the other side of the bridge, after ducking under the arch, was St Nicholas church, but it wasn’t open. Here, when we checked the map again, we discovered that the road lead up to Prague Castle and we could clearly see that inside the walls of the castle was St Vita’s Cathedral. We now had a name for the big black church we had seen across the river earlier that morning.

Changing the guard, Prague Castle

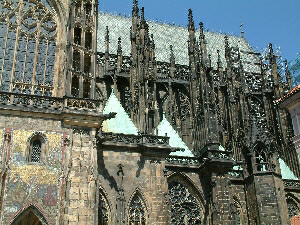

Still, the most impressive thing about the entire cathedral are its magnificently vaulted flying buttresses. My photo, doesn’t really do them justice, but they are a work of art and engineering in one go and they show that Medieval Europeans weren’t the ignorant, religion-soaked oafs of popular imaginings but men who understood geometry and mathematics and were masters of the science of working and building in living stone. The cathedral doesn’t have its treasures any more; they have been stolen and pillaged by successive conquerors of Prague, but as long as the cathedral stands then generations of Europeans can see the real treasure of St Vita’s Cathedral – the genius of its builders.

Buttresses of St Vita’s Cathedral

We spent some time wandering the battlements of the castle in the sun and looking at the view of Prague from such an excellent vantage point, wondering at the strange buildings and towers in the town below. We also took the chance to look through the armour museum, even though there was a small charge for it, and we could see by the size of the armour that military men in the late Middle Ages were at least as big as me (5′ 11″) and many were much larger. I have no idea how they wielded their heavy swords for any length of time.

View of city from Prague Castle

We took the now well-travelled route past St Nicholas Church and over the Charles Bridge to see what we could find in the city. The road ran directly, though not at all straight, to Staromestske Square. We had to pay to walk down Golden Lane, but we thought that for the cost it might be nice to wander down a steep narrow street through a neighbourhood of small houses formerly used by the artillery men of the castle which were now also small businesses.

One of those small houses turns out to be a former residence of Franz Kafka. I had read one of his works, The Castle, about the powerless you feel when grey un-named and un-nameable bureaucrats make – or sometimes even worse don’t make – decisions about you. This was when Prague Castle was still the major seat of government. That feeling of faceless men looking at you, knowing everything about you and plotting with each other to deny you, is called Kafkaesque.

Kafka’s house

The gothic splendour of the twin towers of Tynsky’s Cathedral dominate Staromestske, the large square in the centre of the city. That’s it in the photo on page 1, like something out of DisneyLand, except that it’s authentic. We never had a chance to look inside, but it is immensely impressive.

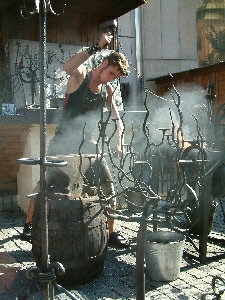

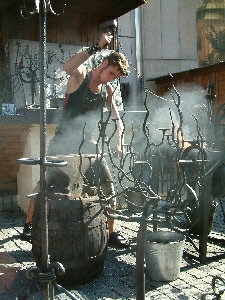

A small market was buzzing at the far end of the square and stallholders were displaying brightly coloured clothes and jewellery and country crafts. We made our way through stalls of hats and scarves and semiprecious stones set into trinkets. A young blacksmith in a leather apron hammered noisily with a short-handled 5-pounder on a flat piece of iron gripped securely to his anvil. He looked like a Greek god and I am sure he knew it. One day the blacksmith will be as modern as a rock band and he will have girls screaming at him while he works, with his neatly cropped beard and the iron-studded wrist band, the swirling smoke and the shriek of his bellows. In the lovely morning sunshine of a full summer day, bathed in sweat and wreathed with smoke, he showed off his power, his balance and his craftsmanship.

Blacksmith, Staromestske Square

On the other side of the square was a most unusual clock. It had two different faces and it looked like it told the time as well as traced the visible heavenly bodies. I stood back to fit it all into my view-finder and tried to take its picture. I always like to get a picture with everyone fully in the frame, no-one cut off at the knees or half-entered at the left or half-leaving on the right. It’s also nice to get a picture of a building with someone in the frame, to give the building a well-used flavour.

Without people in the frame, one building is as dull as the next and just as anonymous. I waited for the opportunity, and took several photos just as things came right, but each time when I looked at the picture in the viewer, people had done something to muck it up. I waited for the crowd to thin a little, not wanting to keep Elaine waiting too long. “Come on, come on, get out of my picture,” I breathed. The crowd thinned and I took a couple of likely photos. When I examined them in the viewer, the best of them still had some confounded woman in the bottom right corner waving at something. Elaine was waiting. I turned around to join her still mumbling about my ill luck.

“What did you do that for?” she demanded.

“Eh? Take a picture?”

“No, tell everyone to buzz off like that. Don’t you know half the people here can understand English?”

“I said it really quietly,” I protested, “no-one heard me.”

“I did. And so did everyone else. Why do you think they all moved? You could get us shot doing that.” She grabbed my arm and dragged me off. “I’ll tell you what, if someone else doesn’t shoot you, I will.”

Clock, Old Town Hall

We spent the rest of the day looking for something truly Prague which Elaine could have in England but would also have a place in New Zealand. It would have to be both useful and decorative; Bohemian crystal seemed the best bet. Between visits, we passed this beautiful and evocative stone building called the Powder Tower. The Lonely Planet said it was true to its name. In the days when the city could defend itself this tower held powder, shot and weapons. It was a landmark for the rest of the time we were in Prague.

By the end of the day, Elaine’s quest had ended with a beautiful blue/green lotus-shaped crystal dish on a deeply cut stand. She would use it for peanuts or dried fruit when she pulled out her Denby dinner set, since it was such a good colour match. I flicked at the edge of the bowl with my fingernail. A beautifully satisfying single tone rang out, fully resonant with its own echoes built in. Heavy too.

Elaine looked at me thoughtfully, remembering a wine glass I had shown her in a story she loved to tell. I was convinced the glass was polycarbonate plastic and I had tapped it on the edge of the table to prove I was right. It had shattered.

“These come in one piece,” said Elaine, “they don’t bounce and they don’t chip. I’m going to carry it.”

“On the train to Vienna, all around Vienna, then Bucharest, then the plane home? Along with your bag and your handbag?”

“Whatever it takes, I’m going to carry it.”