One thing about St Pauls that always takes your breath away is just how magnificent it is. It’s not just huge, it’s not just majestic and it’s not just tall, St Pauls is a monument on the grandest scale; one man’s vision of how God himself should be housed. We have this world landmark building within 10min walk of us and it has always inspired. It was once a huge, square Norman church with a tall crossing tower, that glowered over London but the flames of the Great Fire of 1666 were so hot the lead from its roof ran molten down the streets and the church was destroyed. From such destruction came the inspiration to build in a way that would awe even the Romans. The view in the photo on the right is from Canon St across St Pauls Gardens.

When Sir Christopher Wren was given the sole charter to rebuild the churches of London City, he also submitted a plan to redesign the streets in the grand manner of the piazzas of the great cities of Italy. However, local laws and landowners rights overruled him and he had to stay within the existing street patterns. What a difference he would have made to London if he had been allowed! In the event he fudged his plans for St Pauls and made the church much bigger than he had permission for.

Below is Cardinal Cap Alley on the Bankside end of the Millennium Bridge. Sir Christopher Wren lived in this little white block cottage and often stood in the alley to survey his beautiful, growing creation.

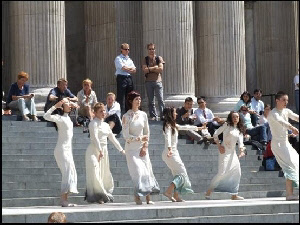

St Pauls is more than just a building; it is an inspiration on the grandest scale. There are always people sitting, meeting and chatting on its steps. Visitors to London who come to see it are often moved to express themselves and their cultures in the amphitheatre created by its steps and the magnificent background of its columns. This busload of students could not contain themselves and in sheer exuberance leapt from their coach and danced in the sunlight on its steps.