The heart of theatre in London is in Shaftesbury Avenue and the streets immediately off it, including Drury Lane. The area these days is marketed as TheatreLand, and even some of the street signs down Drury Lane have this logo on them.

Interestingly, there are TheatreLand signs in Leicester Square – it’s partly justified; Mama Mia is there at the Prince of Wales, and Phantom of the Opera plays in Her Majesty’s in Haymarket, but Leicester Square is more famous for cinema than theatre.

In a place such as this, you also get genuine characters. This chap, below, was just leaving The Dancers Shop on Drury Lane and apart from the garb (including the chain mail skirt) and the hair, he was unusual for the chains and clips attached to every square inch of skin on his face, lips and eyebrows. He gave me a great smile and thoroughly enjoyed the attention he was getting from all sorts of people on the street. A little further down the road, there was a huge sign on the New London Theatre advertising the Blue Man Group.

These stage hands were having a break outside the Theatre Royal off Drury Lane. As I talked with them a huge white bus from France pulled up and about 70 well-dressed late-middle-aged people, having a great time on their London Day Out, climbed down and made for the front door of the theatre.

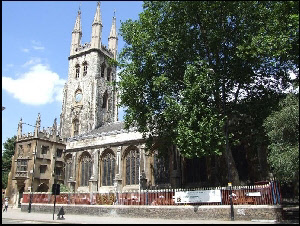

Shaftsbury Avenue was part of the effort to break up the St Giles slum and it gives access from Oxford Street to Piccadilly Circus. On the junction with Drury Lane there is the grandiose Shaftsbury Theatre. Surely everyone has heard of this. Originally, it played Victorian music hall, vaudeville and melodramas, but as tastes have changed so has the theatre. Inside, it is a small, even intimate theatre with excellent acoustics. It has always been home to musicals and at the moment it is playing Daddy Cool. This view, below, of the theatre is from High Holborn and to get there all you have to do is leave Holborn Circus heading up Holborn, follow the road and stick to the left hand footpath all the way.

Shaftsbury Theatre

Some of the famous theatres in the area include the Old Vic (A Moon for the Misbegotten) the Theatre Royal (The Producers) The London Palladium (Sound of Music) The Adelphi (Evita) The Lyceum (Lion King) the Dominion in Tottenham Court Rd (We will rock you) The Aldwych (Dirty Dancing) and, of course, the Shaftsbury Theatre.