Introduction by Richard Tearle:

The weather broke kindly for us, but only after an indifferent start; a light drizzle for much of the early morning but the grey clouds soon rolled away and we had bright and quite warm sunshine for the majority of the time.

In terms of numbers attending, this was the lowest turn out, but we knew that it might be more difficult for many people this time around. Having said that, the people who attended had a wonderful time and there were some very important and interesting stories that came out.

I had stayed overnight in Luton so it was an early arrival for me and a chance to take some pictures of the church and churchyard. Ewart arrived just before the church was opened for us and we busied ourselves laying out the various trees, organising the visitors books and pamphlets.

From vestry to altar, the branch of John 1741. The printouts for other branches are laid over the pews.

Pat Field was once again an invaluable attendee and husband John looked after the refreshments in his own special way.

Elaine arrived a little later with Sheila Rodaway who had timed her holiday in England to coincide with The Meet – and wonderful it was to see her. Elaine had been showing her around Tearle Valley, especially Wing and Leighton Buzzard.

The Meet gets under way. From left: Irene Fairley, Ewart, Steph Teale, and Elaine with Richard and Sue Flecknell and Sheila Rodaway.

Lunch was taken as usual at the 5 Bells and I made a short welcoming speech and then passed the honours to Ewart who delivered a wonderful and very moving tribute to dear Rosemary, whose passing last year was a blow and a shock to us all.

The afternoon passed at a more leisurely pace and we finally wound up the proceedings at around 4-30. One of the last people to leave was Deborah Meanley, who gave both Ewart and myself a signed copy of her book of her poems. I read them that night and they are both wonderfully witty and, in places, quite acerbic!

Sue and Richard Flecknell arrived and Ewart spent some time finding Sue’s grandfather on the Tree – but there is perhaps another story there…

Thanks also to Rod and Stephanie who drove down from Yorkshire just to be here – and in doing so they – and we – made a fascinating discovery connecting Teales and Tearles: it could be that Rod will have to change the spelling of his name on his fleet of breakdown vans!!

All in all, then, a good day in which we were able to concentrate more on individuals rather than generally pointing people towards the right tree.

My thanks to all who attended, to Ewart for all his very hard work and Elaine for her organising skills – not to mention her shortbread!

Richard Tearle

July 2012

About 30 people turned up for TearleMeet 4 but what we lacked in numbers, we made up for in the excitement of our discoveries.

We were especially pleased to see the visit of Sheila Rodaway, who had made the journey from Canada.

It was also nice to see that progress had been made on basic research since the last Meet. There was an enlarged Tearle Memorials in Stanbridge (2012 edition) pamphlet, and many of the branches of The Tree had grown considerably. The John 1741 branch, as you can see in the picture above, stretches all the way from the altar to the vestry. The Joseph 1734 branch simply did not fit in its usual place in the north transept, either, and there were also two trees that had not been on display before – Nathaniel’s Tree and Ebenezer’s Tree.

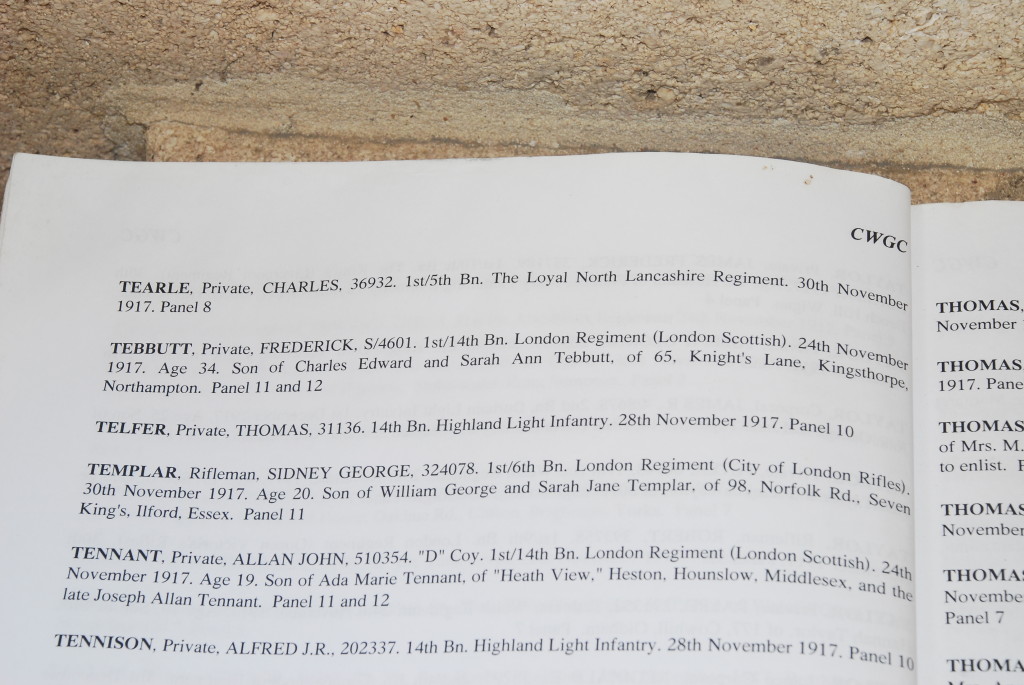

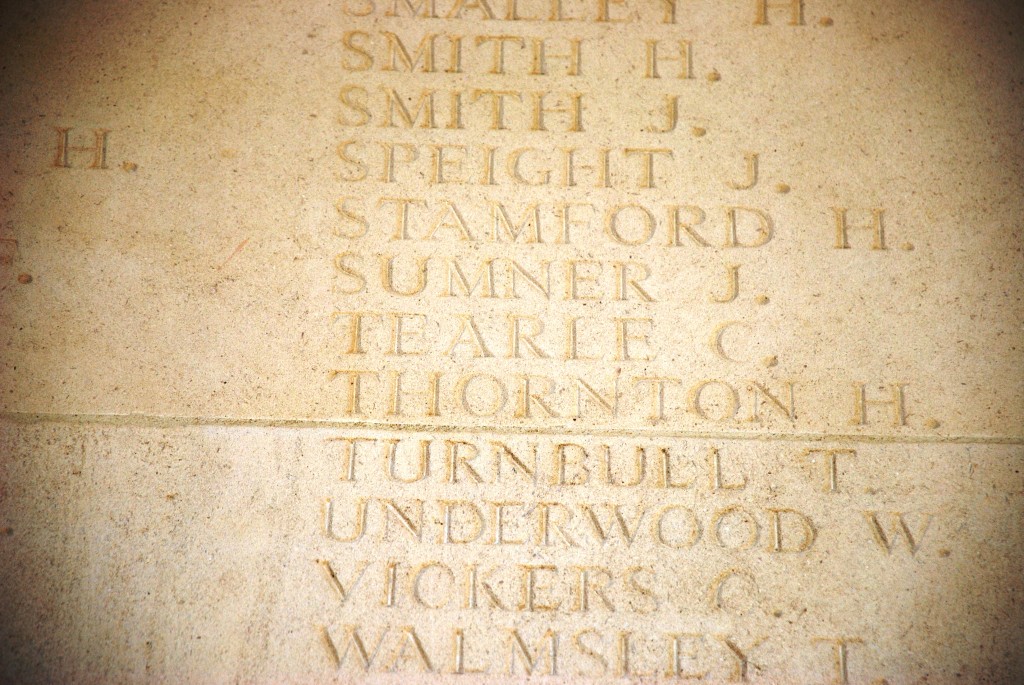

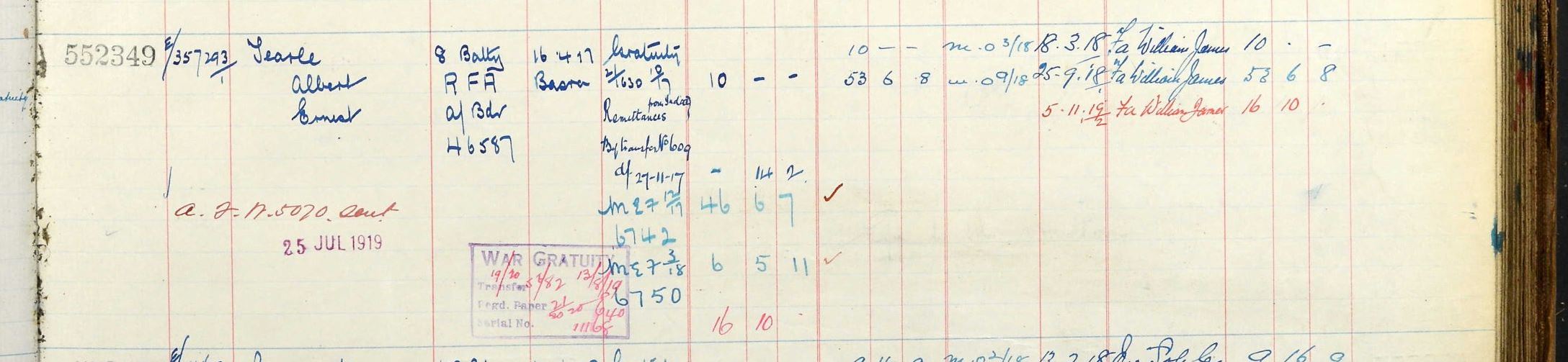

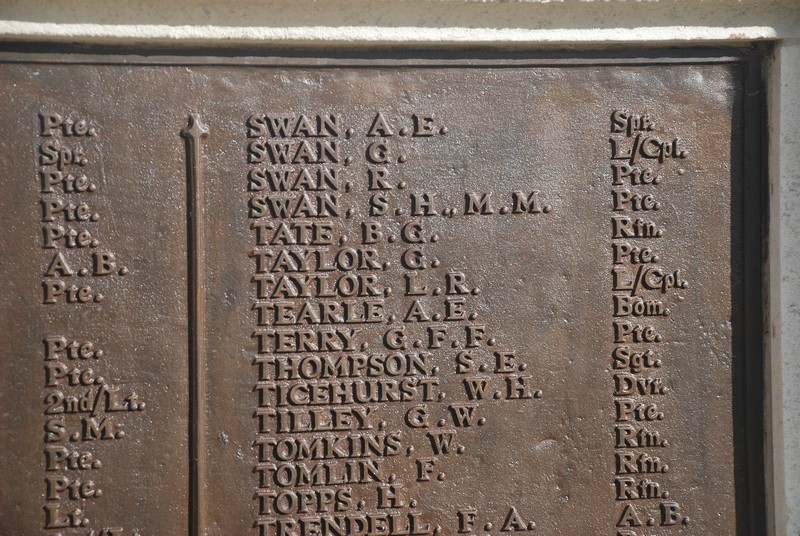

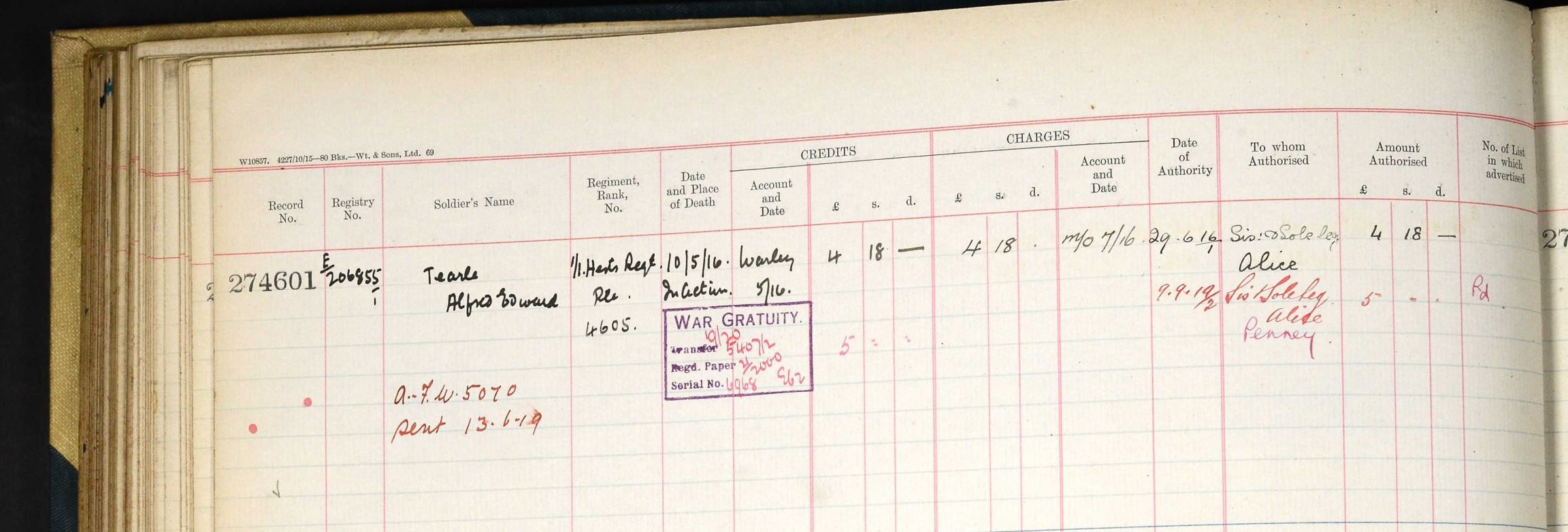

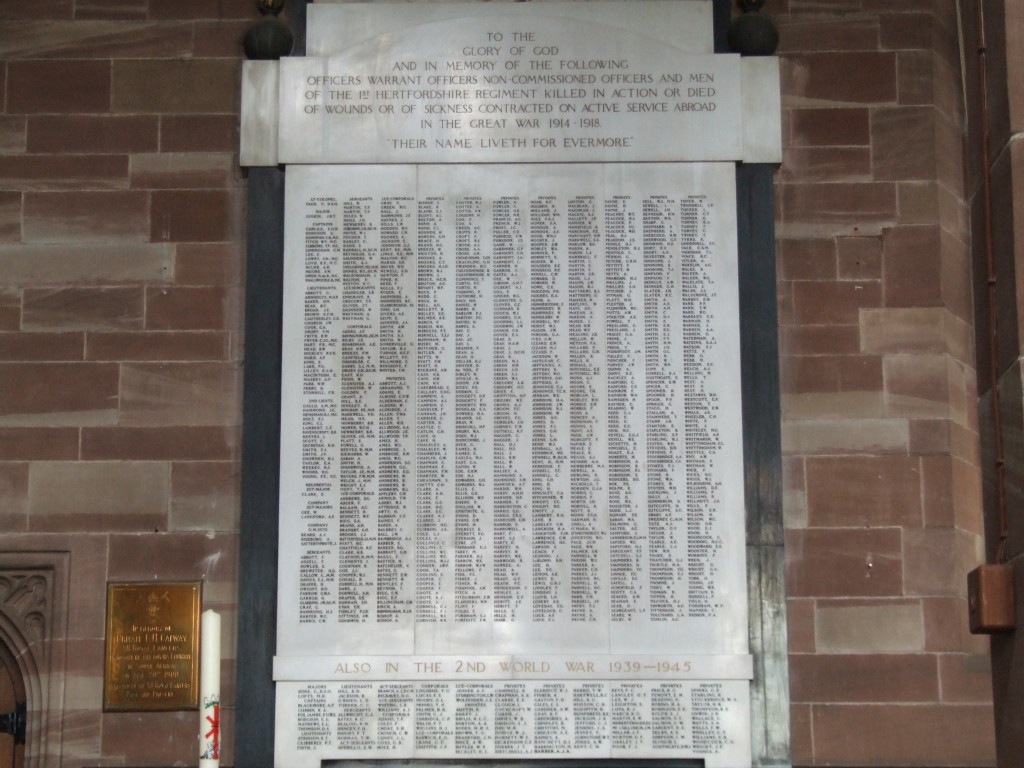

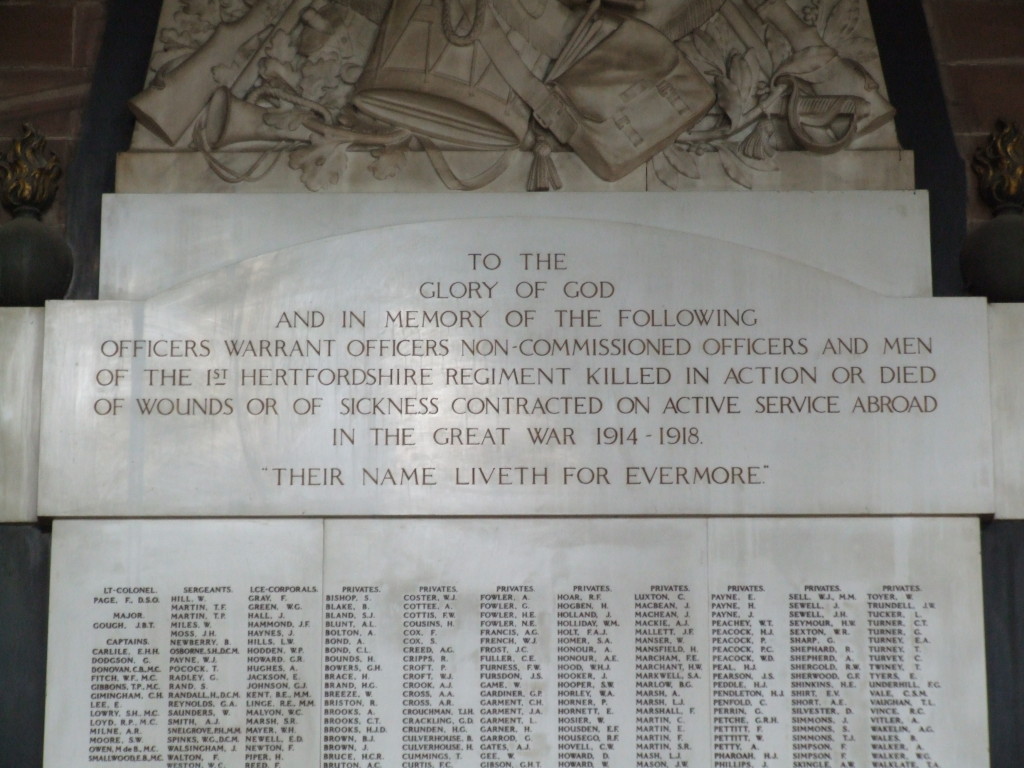

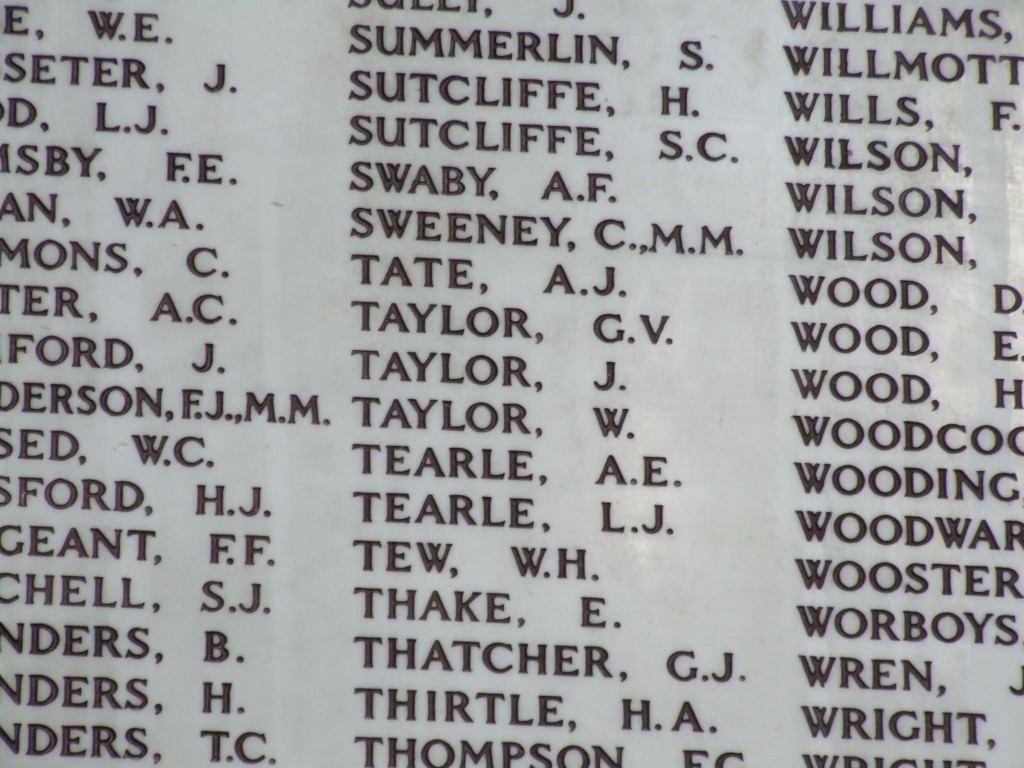

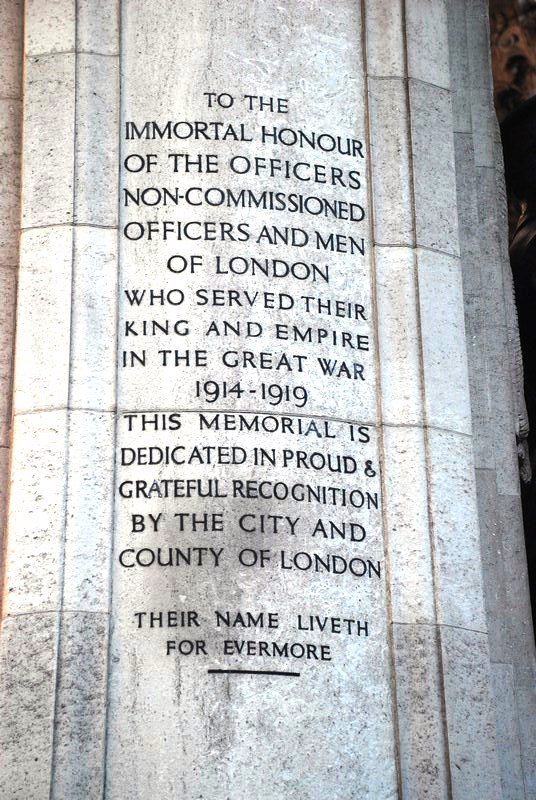

We now have a tradition of honouring our passing family, and a display incorporating a poster for John L Tearle, Rosemary Tearle, and the men and one woman who died in two World Wars was placed near the window, as you can see, below.

We will remember – our gratitude to John L Tearle, Rosemary, and the men and one woman of two World Wars

To complete the arrangements for the day, Elaine had baked a great supply of her famous cookies – shortbread slices and afghan biscuits – while John Field had volunteered to be the Canteen Manager, and Pat Field took up the Front of House position near the entrance door, ensuring that everyone who arrived was welcomed, registered, given a clipboard, documents and pen, shown the exhibits and offered a lunch order. Events such as this cannot be held without the dedicated work of a few inexhaustible volunteers, and we thank them.

Richard’s inspiring welcome message, reproduced below, set the tone for the day, which was welcoming and inclusive, as is Richard himself.

The churchwardens had set out the church documents for people to study: there was the marriage register, the banns register, the burials register and the complete booklet of the Bishops Transcripts of the Parish Registers, begun in 1562.

The little village church from where we originate has a long and rich history, and we are proud to be amongst its children.

We also had on display the greetings messages we received from our world-wide family:

Dear Richard, Ewart and Pat

I hope everything goes well tomorrow – pleasantly warm, not too blustery or rainy, good turnout, interesting networking, good lunch.

Will be thinking of you

Best wishes

Barbara

Dear Ewart & Richard,

Wishing you all a very happy day in Stanbridge on Saturday.

Kind regards

Catherine Brunton-Green

G’day Ewart

Please accept the greetings of Denice (nee Tearle) and I for your Tearle Meet tomorrow.

We have very pleasant memories of the Meet in 2008 and the fine arrangements that were made for that day. Of course, meeting the “Tearles” and seeing things Tearle in Stanbridge was extra special.

Greeting also to Elaine who shared with you in Brisbane meet no 2 and to Richard who inspired the first one on the occasion of his visit.

Our visit last year to your home and your guided tour of parts of Tearle Valley are also remembered with pleasure and gratitude.

I am not sure when it will be but I am determined “we will be back”.

Love and peace

Ray Reese

Thank you. We can assure you that you were missed, and all of us here wish all of you, the very best.

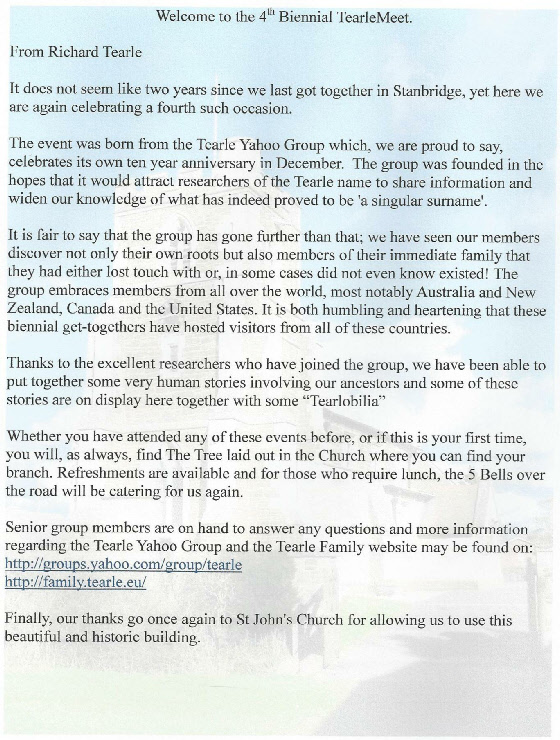

As part of the welcome pack, we printed Richard’s welcome message and included it with the Memorials pamphlet.

What happened?

So now to business. We laid out the branches of The Tree, an impressive 400-odd pages glued together in long strips about three A4 pages deep, and up to seventy-eight pages wide. Once the branches were down, visitors had to watch where they walked, lest they stepped on a branch, or someone on all fours studying a branch.

The rich documentation left for us by the churchwardens, as well as the objects and documents visitors had brought us were an ongoing source of interest.

Sheila Rodaway, a cousin of John L Tearle, talks with Goff and Sharron, below. Goff’s ggg-grandfather was Thomas 1807 who married Mary Garner of Toddington. Thomas was also my ggg-grandfather.

Highlights Part 1

Mary Andrews of Eggington

By ten o’clock, after the usual gloomy, rain-drenched start to a TearleMeet in Stanbridge, the sun was out and some had left the body of the church to explore the headstones, the Monuments pamphlet clipped to a board, pen in hand.

“I’m James Andrews, and this is my wife Margaret,” said a chap with a grey beard and a red striped shirt, who suddenly appeared at the door. “I’m not a Tearle, but my great-great grandmother was Mary Andrews and I know she married a James Tearle. I don’t know anything about what happened after that, but I was hoping someone here might know…”

“She was my great-great grandmother, too,” I grinned. I reached onto the registration table and took a Monuments pamphlet, clipboard and pen. “Let me show you something, and you can read out to me page nine of this pamphlet.” I led off to show them the headstone I had known about since my first visit to Stanbridge in 1997.

“Is it really this easy?” Margaret murmured to James. “The first person we talk to is your cousin?”

“We know a lot about the Andrews,” said James as we walked round the tower and past the great west door. “Mary and her family were all from Eggington.”

“That’s right,” I said. “I don’t know very much about Mary’s family, I’m afraid, but I can give you answers to your first question.” We’d arrived at the headstone and James read the inscription. James Tearle and Mary. He was visibly moved. He had been closely investigating Eggington, he had been researching for years, and here was Mary’s headstone in Stanbridge, almost within sight of Eggington, and certainly a very short walk. We paused while James paid his respects.

“There’s something else,” I said. “Come and have a look at this.”

We walked to a leaning headstone and I indicated they should read the inscription.”Charles Shillingford and Caroline,” he read. He looked up. “And?”

I turned to Margaret. “Now read page nine of your Monuments pamphlet.” She read it out slowly, and when she’d finished she blinked several times, trying to absorb the timeline, but smiling at the last line of Mary’s story. “Much Married Mary,” she quoted, the alliteration tripping gently from the tongue.

“After James’ death, Mary married this Charles Shillingford, and I have a photo of the Shillingfords, Mary and Charles, given to me by Clarice Pugsley. When Charles died, Mary, as Mrs Shillingford, married the brother of both James and John, the sexton, in Watford. Her son, Levi, the blacksmith of Wing, witnessed the marriage. As Mrs Tearle again, she died in 1914, and is buried with James, her first husband. William Tearle, the third husband, has no headstone, which is a shame, but the family of William and Catharine nee Fountain is very influential in turn-of-the-century Tearle history.”

Meeting my Andrews cousin was a highlight of the day for me, and I would have gone home very happy if that was the sum of all that happened, but there was much, much more.

Part 2

Richard and Sue

Elaine appeared at my shoulder while I was looking in Joseph’s branch laid out in the north transept.

“Ewart, this is Richard Flecknell and Sue, and both of them are Tearles.”

Richard shook my hand, “My family is from Hockliffe, but there are gaps in the record, and it seems my gg-grandfather, James 1806, is either an import, which seems unlikely, or wasn’t baptised, which also seems unlikely, or the record was lost, and I think that’s what happened. In the 1930s many of Hockliffe’s PRs were simply lost. Part of Hockliffe lies in the Chalgrave parish, and those records are more or less intact.”

I had a look on Joseph’s branch; I was sure this James had married a girl called Webb. I found them – he did; in fact, he and Mary Ann nee Webb had fourteen children and James was actually Joseph and Phoebe’s grandson. Joseph would have known nothing about little James, but Phoebe would probably have bounced him on her knee.

“It’s a little complicated,” I explained, but we’ve spent quite a bit of time on James, and we are pretty certain he is an unbaptised son of Richard 1778 and Mary nee Pestel.”

Richard looked dubious “Or undocumented, perhaps,” he said, “Given the gaps in the Hockliffe record.”

“That’s entirely possible,” I concurred. “Still, there are very few couples having children in Tearle Valley at this time, so the chance of James’ parents being Richard and Mary is very high.”

“I’ll keep looking for the evidence, but I’m not hopeful any more,” said Richard. “The youngest child of James and Mary Ann Tearle was Emily, who was born in Dunstable in 1852. She married Harry John Bull in 1874 and I’m the grandson of their youngest daughter, Millicent Bull.”

I looked at Sue.

“Oh!” she said with a start, realising the eyes of the group were now on her. Richard Tearle had just joined the group and he, too, was interested in her story.

“My great-grandfather was Levi Tearle, and he was born in Thorn, near Dunstable, in 1855,” she announced.

“Down Chalk Hill on the A5, turn right into a tiny lane marked Thorn and at the end there’s a cluster of farm buildings. That Thorn?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Sue. “The cottages really were for the farm labourers, and there’s even a small cemetery bounded by a wrought iron fence.”

“Levi of the beautiful headstone in Dunstable cemetery?”

“I’ve been there,” she said “I feel somehow that I know him.”

“I have researched a great deal about Levi Tearle of Thorn,” I said, “and everything I found out was a tribute to him. He seems to have been a thoroughly nice chap. It’s a pleasure to meet you.”

Richard cleaned his glasses while he looked at her steadily, taking in a shy, almost reticent, young woman, who seemed surprised at the interest she was generating. “Which of Levi’s children are you descended from?” he asked.

“Levi married Mary Summerfield,” she said, warming to the task and incidentally showing she had researched her family well. “He was always involved in the hat making business in one way or another; either making hats or dealing in the materials that hats are made of.” Richard nodded.

“They married in Dunstable in 1874,” she said, “and they had three children. In 1881, their little boy Sydney George was born and early the following year, he died.” She paused to take in the enormity of losing an infant. “For some reason, they seemed desperate to have a Sydney George, so when their next child, in 1861, was a boy, they promptly called him Sydney George, too. Their next and last child was Edward James and he was born in 1889. He was my grandfather.”

I had found Edward James’ grave under the trees near the road in Luton Cemetery. He had died in 1976. Sue must have known him. “Did you know he won the Silver Medal in WW1? He was wounded at Gallipoli.” I pointed to him on the chart.

Her eyes widened, “I only knew he was in the War and he was injured, but carried on when he recovered.”

“Men who were severely injured were the only ones who were awarded the Silver Medal,” I said. “Usually their injuries were so bad they barely survived, let alone went back into the fray. Your Teddy then fought in Egypt, and the Somme in 1916.”

Richard beside me shook his head. “They were so damned tough,” he breathed. “How on earth did they do it?”

With some pride now at her grandfather’s achievements, Sue handed me a photo. “Teddy is the one standing on the far right,” she said. Elaine laid the photo down and took the picture for us which I am showing below. The two women centre front are cradling rifle barrels and the group are workers at the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. They made Enfield Rifles, bren guns and sten guns, the EN referring to their Enfield manufacturing site. I gathered the Chambering Section worked on the bore and the rifling. Sue’s grandfather, “Teddy,” worked with considerable skill.

“During the War he worked in the Royal Engineers,” I said, studying the photo. “I would think he probably declared his skills when he signed up, so they drafted him there.”

“My grandfather,” said Sue, winding up her presentation, “was a son of William Tearle who married Hannah Pratt, and William was born in Houghton Regis in 1814 to a Richard and Mary.” She stopped.

“Well done,” I said “Your Richard and Mary are also Richard’s Richard and Mary nee Pestel. You are cousins, but very safely distant cousins.” She smiled her shy and beautiful smile, her quest complete.

“Heavens,” she said. “We knew were were both Tearles, but we thought we had come by different routes. Who would have thought we both came from Chalgrave?”

I studied the photograph, and put Richard and Sue in the picture with Teddy. Well, that was a result. But the day wasn’t finished with us yet, in fact it was still building.

Part 3

Rod and Stephanie

“Ewart! Do you know where the Millings family is?” Pat Field was a couple of aisles away and busy showing a couple I had not yet met around the branches, draped as they were over the pews, and spread along the floor. I broke off from talking with James Andrews and thought for a moment.

“They were Methodists,” I said, “so they are probably in the branch of Joseph 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp.” That was where Pat and her visitors were standing, so they bent down and resumed their scan of that huge branch. I seem to remember them visiting all the strips of printout. When I finished annotating the picture Sue had showed me, the couple took the opportunity to step forward. A chap in a grey-blue shirt and an almost white, closely-cropped beard introduced himself and gave me his business card. “I’m Rod Teale and this is my wife, Stephanie,” he said, the Yorkshire in his voice as clear and as open as the smile on his face. A slightly worried red-head, in a black blouse and white jeans, standing at his shoulder smiled diffidently and shook my hand. “We recover broken vehicles throughout Yorkshire, and we guarantee to be there in 20 minutes. It can get a little hectic at times, but we have a fleet of recovery vehicles and we are pretty good at what we do.”

I smiled. It’s nice to hear someone talking enthusiastically about their business.

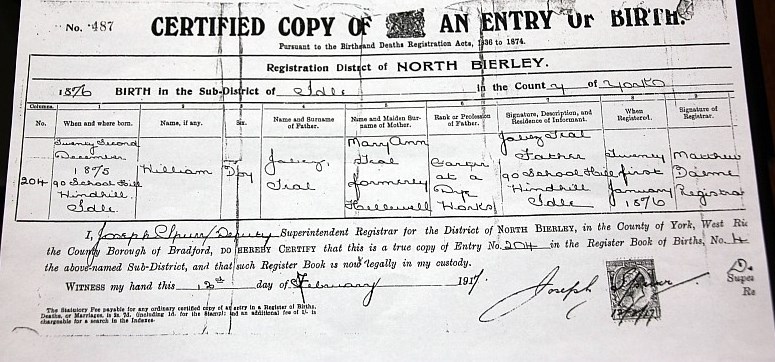

“We’ve spent the past few days in our van coming to this Meet,” he continued, “because we think – actually our daughter thinks – we are Tearles, not Teales.” He stopped for a moment to unfold a sheet of paper that turned out to be the birth certificate of a baby boy called William Teal who was delivered safely in December 1875 in a place called Windhill Idle. I couldn’t tell you where on a map Windhill was, but I knew from another family in Yorkshire that it was in the Bradford / Leeds area. Were these the Wortley, Leeds, Tearles?

“William was my grandfather, his son Willie was my father. I – we,” he put an affectionate arm around his wife’s waist, “have a son Rodger Teale and a daughter Charlotte. It was Charlotte who says we actually come from Bedfordshire and our name is Tearle. She heard this Meet was on, so we took a few days out from our business, and came down here to see if we could find any answers to Charlotte’s questions.”

“We were talking with Pat earlier,” said Stephanie, “and she thinks that Jabez’s grandmother was a Millings, so that’s who we were looking for. Pat says the Millings family is somewhere in those printouts.” She waved an arm over the entire expanse of the interior of Stanbridge Church.

I took a closer look at the birth certificate, the only proof they had that Charlotte might be right. William’s father was Jabez Teal and his mother was Mary Ann Teal, formerly Hallewell. Now, Hallewell definitely rang a bell.

We were standing at a small table in the centre of the church, and the Joseph 1737 branch was on the floor off to our right. Since it didn’t fit in the aisle, I had left the last few metres of the printout rolled up, as it had been in the tight confines of the boot of my car. I couldn’t accurately place the name Jabez, because there are 12 Jabez Tearles in the full Tree, but the Mary Ann Hallewell I knew was a Lancashire lass, and she had married a Jabez Tearle in Yorkshire. I walked quickly down the printout and couldn’t find Hallewell, or Millings, so I unrolled the end of Joseph’s branch and there was Mary Ann.

“Here we go,” I said and Rod looked hopefully over my shoulder onto the printout; to the mass of names in tiny type organised in a wildly random pattern, joined by lines of different width which dived off in various angular directions. Stephanie stepped over the printout and looked at the names upside down, waiting for their order to be explained. “Here is Mary Ann Hallewell,” I said, pointing to her name in what had become the centre of the printout, “and here is Jabez Tearle.” I pointed to the box around his name. Born 1851 in Stanbridge, married Mary Ann Hallewell in 1891 in Calverley, Yorkshire. Occupation: 1873 in Calverley, Labourer; 1891 in Ravensthorpe, Teamer. I looked at Rod for an explanation.

“The birth certificate says Jabez was a carter in a dye works,” he said, pointing to the certificate, still in his hands. “So, he’d be running horses. That’s what makes him a teamer. Perhaps because of his farming background in a rural village like this he was used to working horses, and he got himself a job with a team pulling drays. He’s working in the cotton industry, as you can see, because he’s working around a dyeing plant. At least he didn’t have to go mining,” he said with some feeling. He had inadvertently touched on the family in Wortley, Leeds. They were miners.

Death 1893, Dewsbury.

“We come from Dewsbury!” said Stephanie, seizing at last on an upside down word she recognised. “Once the family moved there, it looks as though we haven’t left since.”

I didn’t quite get it. I must have been looking puzzled, too.

“Our business is in Dewsbury, we really do live there.”

The penny dropped – this family has been in Dewsbury for more than a hundred years.

I paused for a breath. A few bricks had fallen into place, but you couldn’t make a house of them, yet. I scanned the certificate on my printer, and I have presented it above.

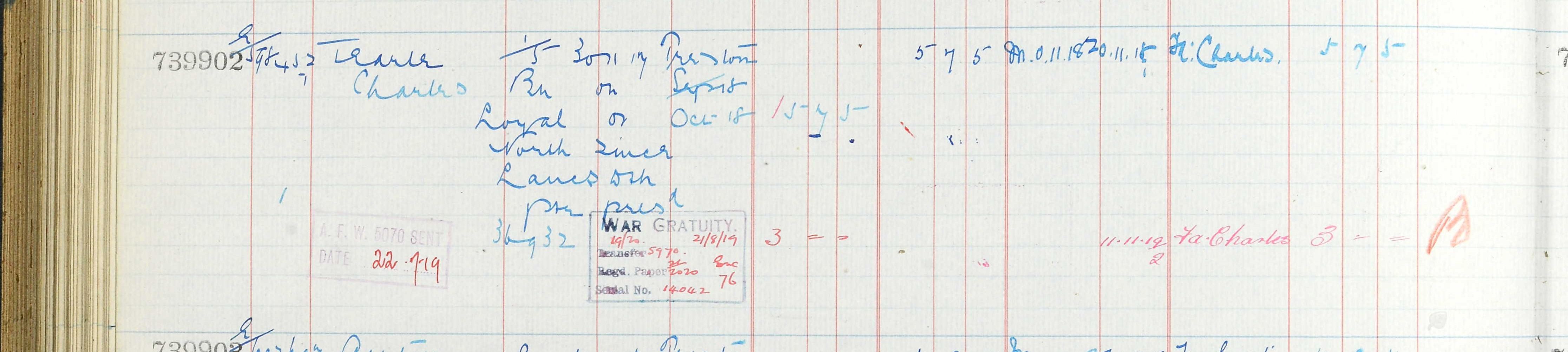

“Did you know William was in the First World War?” I asked.

“Yes, but only vaguely,” said Rod. The chart was quite clear – he was in the Machine Gun Corps, and in two regiments, since he had two regimental numbers. “Why two numbers?”

“Probably because the first regiment was decimated in battle, and the soldiers were transferred to another.

Rod was aghast at the sudden reality of battles so vast they destroyed whole regiments – and then the survivors were transferred to another, to continue fighting. ”Good heavens, what on earth do you think he had to endure?”

I paused while all of this sank in. Finally he turned back to the chart. “Did you know Clement Crowther?” I asked, pointing to William’s sister’s son.

A more homely vision replaced the war-torn landscape of the sea of mud that was Belgium in WW1; a dreamscape of being young and going on holiday, and visiting family. “Yes I did!” exclaimed Rod. “We went there quite a few times. I was told he was a cousin, but I was never clear just who he was.” He looked at the chart again, more closely this time, trying to add up all the details. “Aunt Ann.” He pursed his lips and blew out his cheeks in frustration. “Why didn’t I take more notice?”

I bent down to the chart and pointed to Jabez. “Now, if we follow this line from Jabez, you’ll see his father was Joseph Tearle, born in Stanbridge in 1797. He married Maria Millings.”

“That’s the family we were trying to find with Pat,” said Stephanie.

“They were a Soulbury family whom we had called Milward,” I explained. “We were contacted by the Millings family who told us what the modern spelling and pronunciation is, because, as you can well imagine, with Victorian laissez-faire spelling coupled with a lack of literacy on the part of the owner of the name, and difficulties by various historical bodies in transcribing handwritten documents, we had a variety of spellings. This is the one we have all settled on.”

“How do you know they were Methodists?” insisted Stephanie.

“Way back in the middle nineteen eighties when I was researching the Tearles in the Mormon Family History Centre in Hamilton, years before Elaine and I came to England, I found the Wesleyan Baptism Register from the Luton Circuit, filled out in Victorian times. Joseph and Maria nee Millings were in that register. Do you see Emma, Jabez’ sister?”

Everyone took a closer look at Jabez’ family.

“She married George Brightman of Soulbury, probably her cousin, and by 1884 she’d had 11 children. In late 1883 George died and by 1886 some of her children, and her brother William had emigrated to Australia, so she moved there to see what Australia had to offer. In Cooktown, a wild frontier town in North Queensland, she married a local character and womaniser named McGhie. The marriage didn’t last long because shortly afterwards she and William, and her youngest children, Habbukuke and Emma Jane Brightmen left on the Quetta for England. Early in the night sailing, while navigating one of the channels heading out to open sea, the ship hit a rock and sank in five minutes; Emma, William, little Habbukuke and Emma Jane all perished.”

Stephanie gasped and leaned the back of her head on the wall behind her, thinking of Emma in the darkness trying desperately to save her children. Jabez had lost his eldest brother, one of his sisters, a nephew and a niece to tragedy in a place so far away, it could have been on another planet.

We had exhausted almost all the information the birth certificate, and the chart, had to offer. I walked along the chart to find Joseph’s father, Jabez’ grandfather. It was William 1769, who had married Sarah Clarke. His brother was Richard 1778, who had married Mary Pestel.

Richard Flecknell, Sue and Rod were cousins. This is Stanbridge – things like that happen in a village.

Rod looked thoughtful. “So we are Tearle. That’s established, isn’t it?”

“Yes it is,” I said. “William is your grandfather, and the documentation for him and for his ancestors is compelling.”

Rod looked at Stephanie “What do we do now?” he asked.

“You’ll have to change the spelling on all your recovery vehicles,” I grinned.

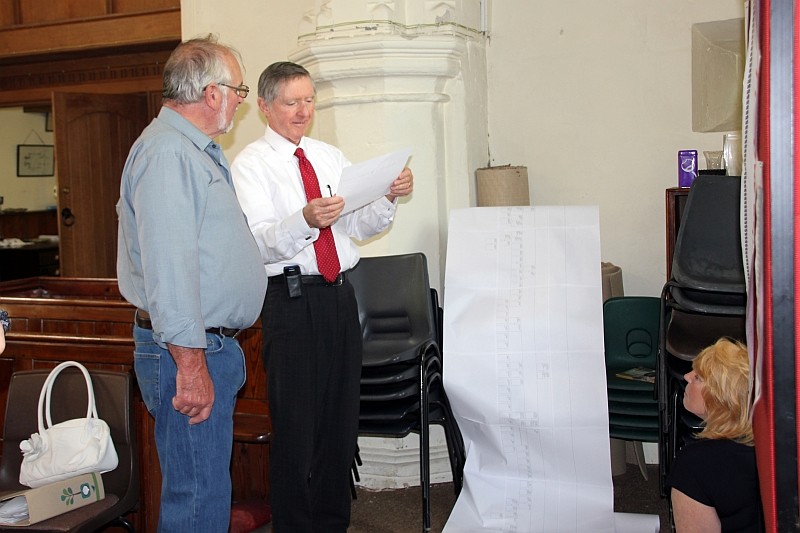

The moment of discovery – Rod Teale is actually a Tearle. Not so much a new Tearle family, as finding one which had disappeared.

Part 4

… and Deborah

Deborah Meanley contacted us to gain some details on her ancestry, that she had been unable to find by herself. She provided us with information about herself, and what she had found out about her family, and we had been able to supply her with fillings for the gaps in her family history. I added all the new information to the Tree, and Deborah said she would come to Stanbridge to see the result.

It turns out she is a descendent of the Tearle and Pantling marriages in Eggington in the 19th century, and therefore she is on the John 1741 branch, the same as I am, and which Mary Andrews of Eggington had joined. Her gg-grandfather, Richard Tearle 1794 married Dianah Pantling and their son, David 1818 married Deborah Pantling. I haven’t quite unravelled the intricacies of this but I wouldn’t be surprised if Deborah was Dianah’s niece. Thereafter, her family was in Dunstable; a classic Tearle story. In the 1911 Dunstable census, Deborah Tearle nee Pantling was living with our Deborah’s grandparents, in Dunstable, along with both of the in-laws and five children, one of whom would become our Deborah’s mother.

She proved much more interesting than the sober and somewhat scholarly person who had written to us. She spent much of her time in Stanbridge carefully looking through her branch of the family and noting the stories she found there. The couple of times I was able to speak with her, she was acutely aware of a lack of hearing.

“Excuse me if I don’t always get it the first time,” she said wanly. “Sometimes I have to hear it twice to pick up all the words. Deafness is such a curse because it strikes at the very heart of what it means to be human – we communicate in speech.”

She generously gave Richard and I a copy of her book Mother’s Prickly Poems and autographed it for us, as well. In it are some generous and fulsome, kindly and insightful, beautifully crafted poems, along with some deliciously acidic and biting commentary on people who should know better, but who set their own standards very low, and then always failed to meet them. The advice she gives her children comes straight from the heart, and from her own hard-won experience. Her most beautiful and touching poem is that written on the death of her younger brother who died in 1985 in a diving accident; “Farewell to a skin diver”.

Come and visit us whenever you like, Deborah.

Part 5

Lunch at the Five Bells.

Deborah is right in her comment below; much of the Five Bells is new, but the old part, where you enter, would have been familiar to Stanbridge residents as far back as the 1600s. The low-hanging oak beams, the thick oak planks on the floor and the smell of English ale tell stories to each other that only they remember. It’s as much a part of the Stanbridge landscape as the church itself.

Lunch at the Five Bells: Rod Teale, Tricia Milne, Irene Fairley, Sheila Rodaway and Deborah Meanley. Behind Deborah – John Field, Goff Tearle and Sharron.

Part 6

The end.

For me, TearleMeet 4 was a day of high drama and satisfyingly unravelled mysteries. I enjoyed it thoroughly. A TearleMeet is not about who comes, or how many come; it is entirely about the quality of the new discoveries that only such a personally attended Meet can provide. Can I please thank Richard Tearle, Elaine, and Pat Field for the photos above, and their permission to publish them here. Can I also thank Pat, Barbara and Richard for their ongoing efforts to make the Tree as complete, as accurate and as comprehensive as it can possibly be. Without their work, the Tree simply cannot grow.

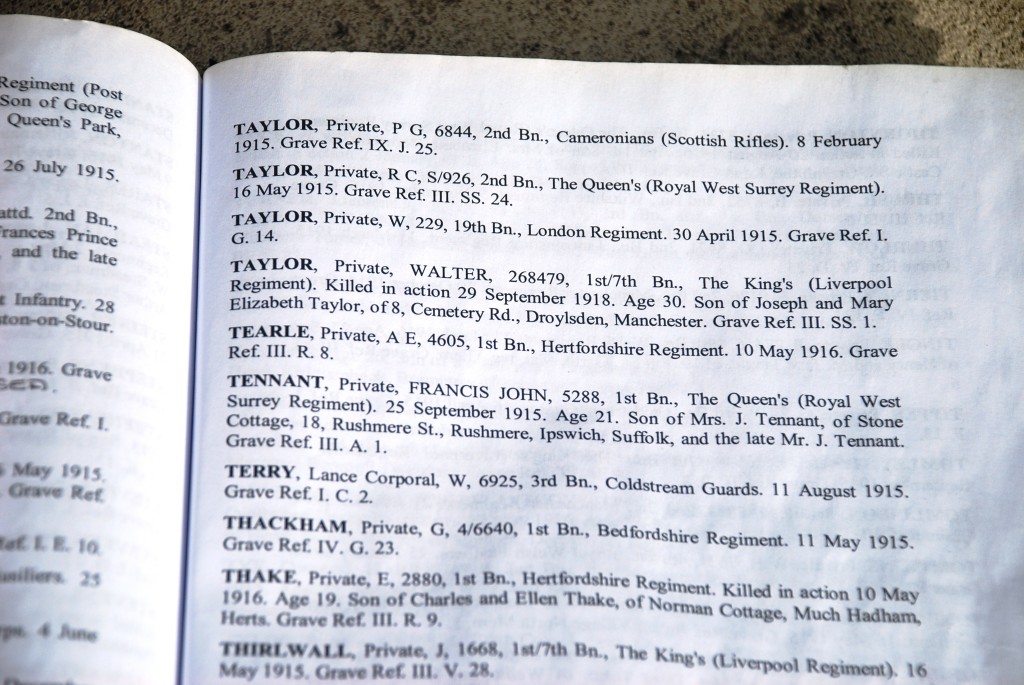

Because I am a son of a country of the ANZACs, I take a special interest in the Gallipoli campaign. ANZAC Day is the most important national day on the New Zealand calendar, transcending politics. I now know of three Tearle men who fought there.

1. John Henry Tearle 1887 (9054, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers) of Hatfield who left his mother in Bengeo, Hertford, and joined the British Army. He was killed on 29 June 1915, and is memorialised on the Helles Monument, overlooking the Dardinelle Straits. He was a son of dreadful poverty, and both his grandparents spent time in the debtors prison in Hertford.

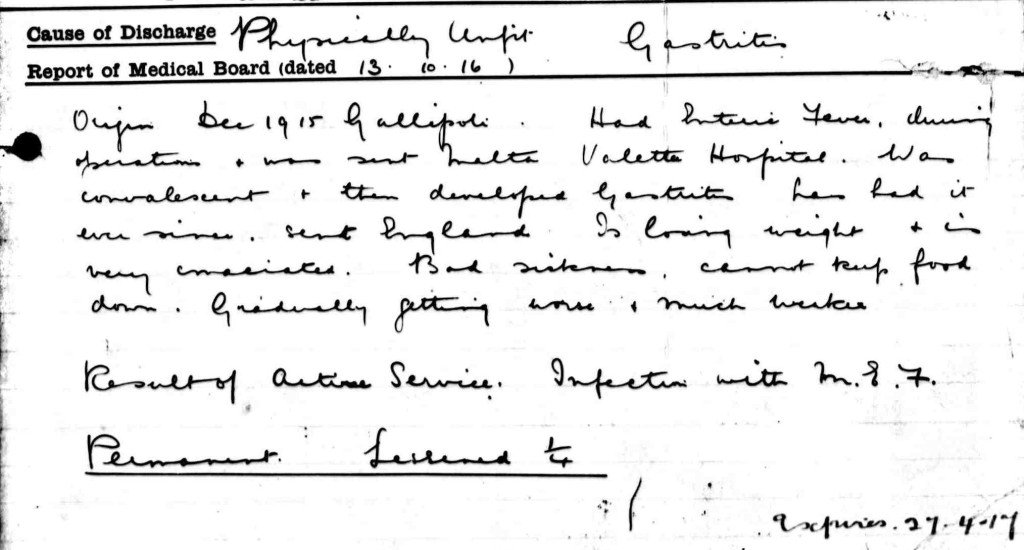

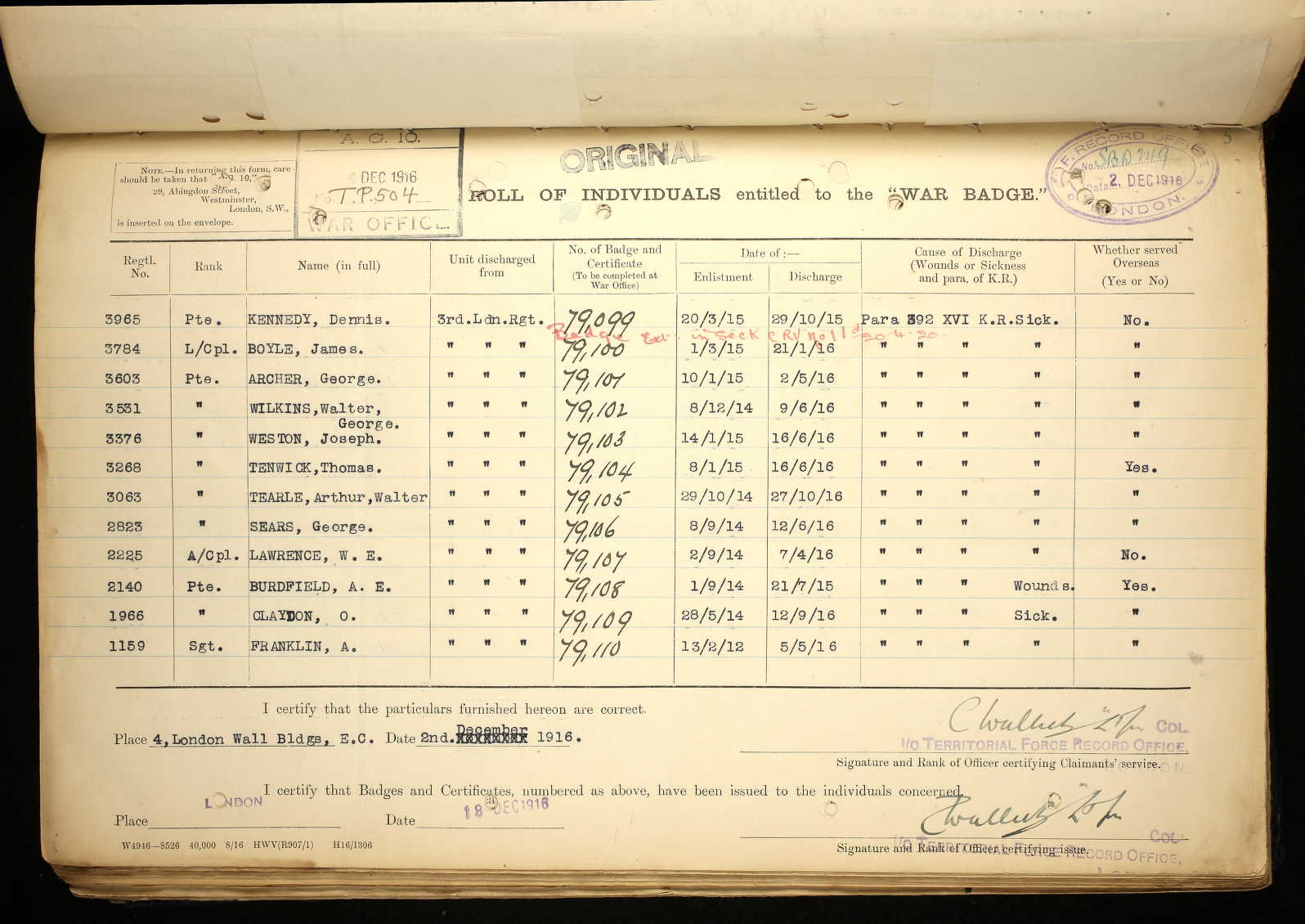

2. Edward James Tearle 1889 (101941, Royal Engineers) son of Levi 1855 and Mary nee Summerfield, Teddy was wounded at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, but went on to fight in Egypt and the Somme. He was invalided out of the army and awarded the Silver War Badge.

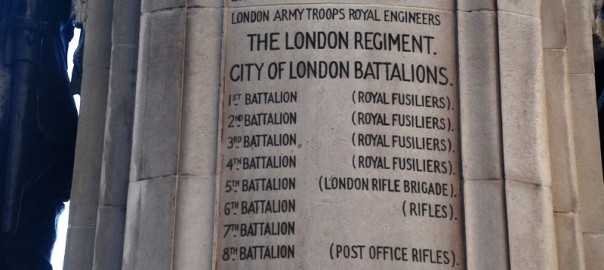

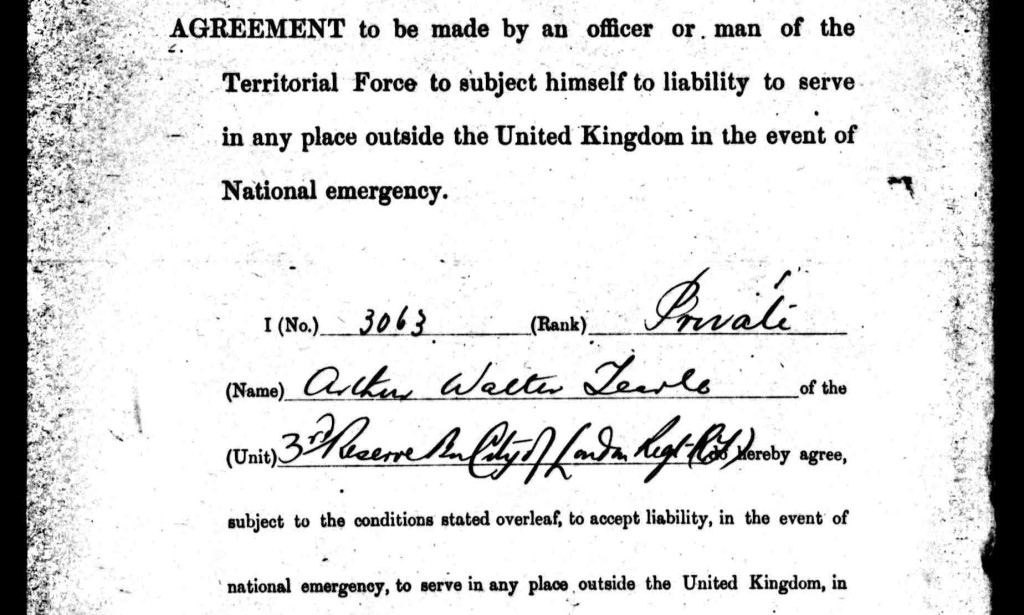

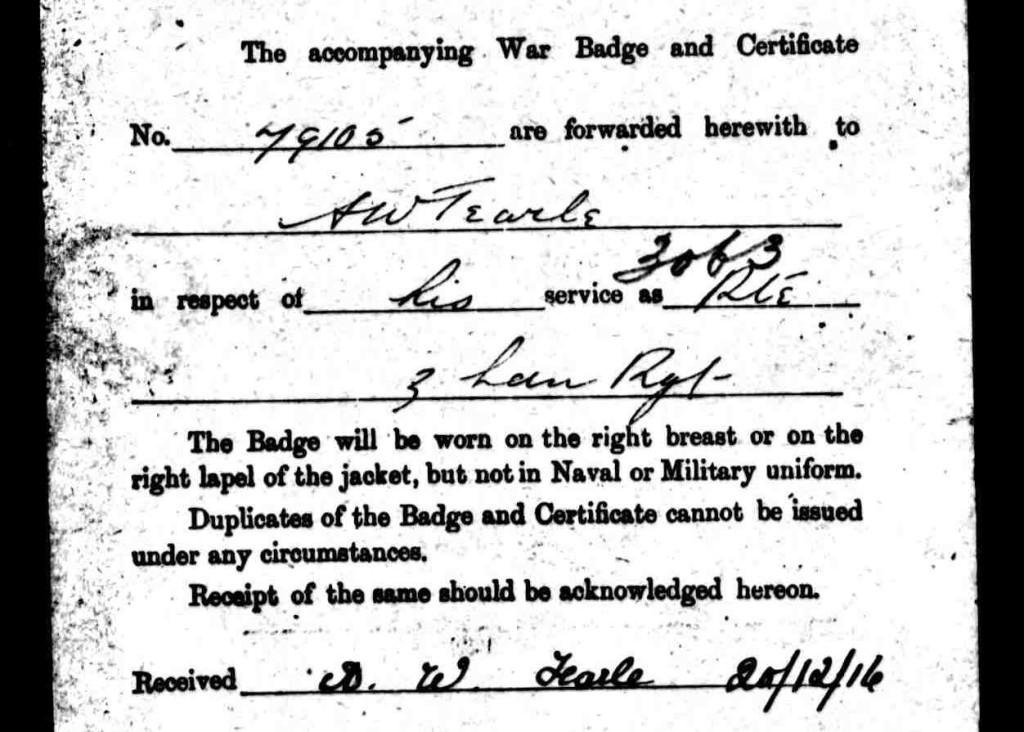

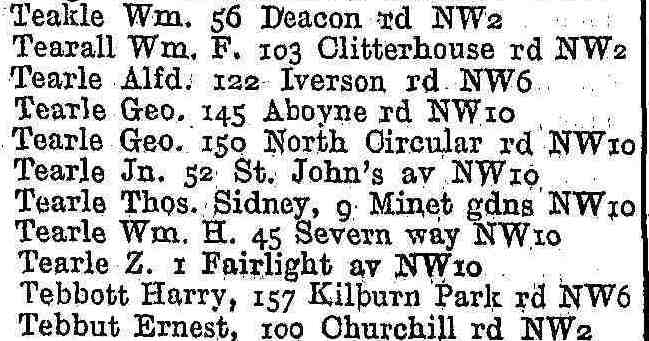

3. Arthur Walter Tearle 1880 (3063, London Regiment) who was wounded in Gallipoli, and contracted typhus. He was repatriated to Valetta Hospital in Malta, and later fought in Egypt. He also was invalided out of the army, and received the Silver War Badge.

TearleMeet 2012

Deborah sent a message …

Thank you to Ewart & Elaine, Richard and Stewards for making the Day so ‘special’.

Apologies for delay, due to overload with grandchild minding and House Sale complications .

The whole day was enlightening and nostalgic for me as it reinforced my sense of belonging to the Hougton Regis, Harlington & Luton triangle despite no longer having elderly relatives in area since 2003. It is such a pity that there are no longer any brothers or elderly relatives to share the new findings with.

The Meal at Five Bells also had meaning – as it was probably almost unchanged since used by our ancestors?

Sorry that I was unable to take new information on board quickly, due to the combination of deafness and stroke damage a few years ago.

I finished off the day with a delightful five hour visit to late Aunt Audrey/Babs ‘ 93 year old friend in Harlington and had a quiet journey home – arriving there just after midnight .

Warm wishes

Deborah

As did Barbara

Richard

From one who was not there – a nice report. Pat had told me that numbers were down, which was a pity, but, as you say, it provided the time to concentrate on helping individuals and discovering more stories.

I’m sure that it was a lot of work again and it is marvellous that the meet is carrying on, thanks very much to your enthusiasm and persistence, Ewart.

Best wishes

Barbara

And Sue Albrecht of Auckland

Hi Ewart and Elaine

I hear from Richard that the latest Tearle meet has been as much fun as the others, albeit a little smaller than previous ones?

Richard also tells me that there was a man there who mentioned that his grandfather(?) was a James Tearle whom he could not link to the tree. Could be no connection, but my father was a James Tearle who cannot be linked to the tree either. He died in Perth in 1992.

If our James Tearle cannot be discounted on that information alone, it might be worth pursuing further?

Freezing here. And Auckland is in the grip of a vicious virus, and none of us have been spared!

Sue

And Sheila

Hello Ewart and Elaine

Many thanks for everything last Saturday. You both do such a wonderful job in organizing this meet. My special thanks to Elaine for driving me to/from Leighton Buzzard and a tour of Tearle Valley, it was a very special day.

Thanks again

Sheila