Here is the obituary I wrote for Mum’s funeral:

For my mum, Tia Tearle.

For longer than I care to remember, I have dreaded this day because from this day forward I have to face the future without Mum. I can no longer ring her up and talk to her, and I can no longer write to her. All I can do now is to commune with the memory I have of her. But this day had to come; death is one of life’s absolute certainties, it happens to us all and there is no appeal.

The Queen recently said, “Grief is the price we pay for love.” The hurt and the pain we feel, and the tears we cry, are all because of the love we have for Mum. But in spite of that, however sad we feel and however much loss we suffer, today is not a tragic day; it is a day of rejoicing in a life full of richness and many friends, full of laughter and a wicked sense of humour.

Although poverty was a constant companion in her childhood, Mum grew up in a relationship with her father and older brother Maurice that was rich with incident and variety. I shall be forever grateful to her younger brother, my Uncle Dick, for coming to New Zealand a few years ago and helping her to lay the ghosts that had so haunted her life and the memories of her family. James Ewart Dawson was a tall, gaunt man of immense physical strength and strong moral fibre, with a wonderful laugh and a generous, humane nature. Her father gave her from his huge heart the unbounded generosity which so enriched her life. He also gave her a lifelong love of horses. This was a mixed blessing. “Racehorses,” she used to say, “kept us poor.” But it was a passion she shared with her father and through it she met jockeys, trainers and some memorable horses. She had even groomed the mighty Phar Lap.

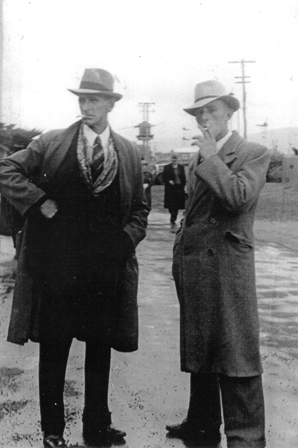

James Ewart Dawson, Tia’s father (left) with Maurice, her brother, at the Wellington races. James was known as Lofty by all who knew him. The Dawsons were from Lisburn and Belfast.

My Mum was also a lady of definite opinion and she hated pretension. She was home early one day from her job as a nurse’s aide in Rotorua Hospital when I was still in Intermediate School. She was sitting with her neighbour at the table in the window of our Western Heights house and she was alternately laughing and crying.

“They’ve sent me home early,” she said. “This horrible woman had moaned and complained about everything from the moment she woke up. When we made her bed she wanted to be left alone. When we left her alone she complained because we hadn’t adjusted her pillows. I took her the morning’s porridge. It was nice and warm, I had poured the milk on it and there was a heap of brown sugar just as she liked and she said to me, “What’s this stuff? I don’t want porridge today I want toast.” I couldn’t stand her any more! I said to her, ” Well if you won’t eat it you can wear it,” and I threw the plate of porridge all over her.”

She had genuine steel in her, too. I was very sick in my third form year and Mum stayed home to look after me. I was hot and feverish and she rang the doctor, but he was busy. I can still feel the resolution and determination, I can still hear that icy tone as she instructed him to come and see me. And he came. After his examination he declared I had tetanus, but it should be treatable because it had been diagnosed at an early stage. I ate pills the size of Oddfellows for a week, but it may well be possible that she had saved the life of her middle son.

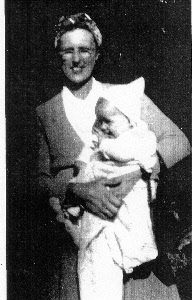

Tia’s boys. I’m the one in the middle, in my school cap and jersey. The boxing is around a pipe that fed hot mineral water into a very large bathing tub. It was closed later due to fears about poisonous gas.

So what are the memories of my mum that I shall particularly treasure?

Mum drove me to Hamilton each month for a year to see Mr Davies, the orthodontist, who straightened my teeth. Gertie the Anglia could run at 45mph “cruising nicely,” said Mum and 60mph downhill with the wind behind her. We drove up the narrow, winding metal road through the Mamakus and Mum would curse at the car in front if it slowed her down on an especially steep, windy bit. “Look at that,” she fumed, “a bloody great Vauxhall. That silly bugger’s got more power in his car than a dozen of mine, and he slows me down on tight corners like this. It’s all right for him, but Gert takes a long time to get back to speed if she’s slowed down right now.” She tooted and the car ahead surged away. “See?” she said. “He just needed reminding to concentrate on his driving and stop thinking about his floosie in Rotorua.” I don’t remember a single conversation – if we had one – but I remember the feeling of being special because Mum was doing something for me alone.

During the summer of my 6th form year – my second 6th form year, I think – Mum didn’t go to work and she asked me to come home for lunch. As I walked along the road behind our house I could see the house across the gully and Mum would wave to me from the dining room window. When I arrived home we would sit at the table in the window and eat our lunch. It seems to me now that every day was a sunny day because I can only remember blue skies and bright sunlight across our back yard. There are few more precious memories in my life.

I had trained for weeks to do well in our annual High School Cross Country race. The day of the race was sunny and warm and we ran up the very steep slope of Ngongotaha Mountain, down the newly sealed roads and then past our house in the last mile of the event. I was exhausted. Suddenly I heard Mum’s voice. “Go, Ewart – you’re third!” I couldn’t believe that Mum had come outside to watch me run. I don’t know why, but I was really surprised. I tried to run down the boy in front of me but he heard me coming and kept surging away any time I got closer than about 50 feet. I ended up third, all right. There is a little corner of my mind where I can still hear Mum encouraging me.

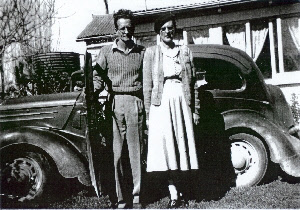

Tia and Maurice Dawson. Morrie ended up slightly brain-damaged after a fall from a pony, and died in his late middle-age, never marrying.

She taught me a lesson about women. Whenever it was Dad’s birthday, or at Christmas time, I would get him something he wanted, like a drill or a chisel, so when I was about 10 and Mum’s birthday was coming up, I heard her complaining about her eggbeater being almost useless and a lot of work to get it to go properly. So I bought her an eggbeater for her birthday. To my utter horror she just cried.

“What’s the matter? What have I done?”

“It’s my birthday and you have given me tools,” she sobbed.

“What should I have done?”

“You don’t buy a woman tools,” she said. “I am not someone who just works for you all in the kitchen. You could have bought me something nice, like perfume.”

I had never thought of her as a woman. I was shocked. It is a lesson I have never forgotten and a lesson I have completely subsumed.

For the last 20 years we have taken our Christmas holidays at Pauanui. Every year we have had Christmas with Mum and Dad and for the past 10 years or so, they have travelled to Pauanui on Jason’s birthday, the 3rd of January. It has been a time that brought us closer together and given our children a good sense of their grandparents.

She had so many friends! Any time you sat in Mum’s living room for more than an hour, you would meet someone who was just dropping in to say hello. Some of them were her friends and neighbours calling in to give back a plate that Mum had given them full of biscuits, some were calling in to give her a present. Some of them were the stray pups she picked up as part of her AA work, calling in to get a little encouragement, a few words of advice or a good kick up the bum.

Mum’s fundamental belief was that nothing would happen of its own accord – you had to want it to happen first. If you wanted change in your life, you had to recognise that change was necessary. Until then no-one could help you, and she wouldn’t hesitate to say so. She had half a lifetime of helping people and she gave them the help they needed, even if it wasn’t always what they expected. People loved her because she gave. But she had a keen eye for the bludger and she didn’t suffer fools at all.

So in the midst of your sorrow, reserve a space for happiness and laughter. Mum had a huge and infectious laugh and if her sense of humour didn’t always overwhelm her immediately, she could see the funny side once she calmed down. Today is a time of music because she loved to sing and dance and play; today is a time of sadness and tears because she is gone and we shall not see her again in our lifetime; and today is a time for laughter and telling stories. She was our Mum; no-one can ever take her place and we shall love her for ever.

In a little chapel in our wonderful St Albans Cathedral two small candles are burning bravely. One is for my beautiful son and other is for my lovely, lovely mum.

Fly towards the Light, Mum, for in the Light there is peace.

Ewart Tearle

St Albans 2002