By Ewart Tearle

8 April 2015

The dual carriageway from Istanbul to Eceabat is long and winding and takes the best part of five hours driving. The countryside is green and pleasant with a patchwork of fenced fields on a wide and gently rolling landscape, sometimes resembling the Waikato, with its grassy green paddocks, and sometimes looking like Hertfordshire where knots of tight forest capped low rises. Small villages of unkempt cottages with broken tiles on the roofs told of rural poverty, little mosques with one dome and a single minaret lent romance to the valleys.

A little village mosque.

“We are travelling the coastal highway of the Gallipoli Peninsula in the Province of Canakkale,” said Kubra, our beautiful guide on the minibus to Eceabat, a slim young Turk in a wide-skirted brown trenchcoat that swept to her knees, her hair covered with a silk scarf that framed a face of peaches and cream with dark eyebrows over brown-green eyes. “All of the peninsula falls within the province.”

She looked through the bus window towards the sea thirty or forty metres below. “The houses between us and the sea are holiday homes, that’s why there is no-one in them.” For many miles the two-storied houses, with their tightly shut windows and locked doors, their sun-powered water heaters sticking out of their roofs, stalked up and down the slope to the sea, a few hundred metres away, waiting for the holidays. The rural cottages had no such sophistication. We saw very few people, even in the villages – and no stock of any sort.

In Eceabat, we found TJ’s Tours; it was they whom we had asked to take us to the ANZAC battlefields of the Great War. Genevieve had recommended them.

“Why are you going there?” our English friends had asked us.

“Because we are Kiwis,” we’d say.

When I was a Boy Scout, from about the age of fourteen, every ANZAC Day, on the 25th of April, I had been a member of the guard of honour around the Cenotaph in Rotorua, head bowed in the dark, foggy cold of a 6am start while small, old men honoured their lost friends with wreaths and tears. It was called Dawn Parade. There were soldiers from the Boer War, from the First World War accompanied by a small contingent of nurses who had served on the battlefields with them, and a larger section of men and women in uniforms of soldiers, sailors, air crew and nurses who had served in the Second World War. The deeply sad wail of a single bugle sounding The Last Post hung in the eerie silence while the grief-stricken sobs of women my mother’s age were muffled in the coats of their friends. New Zealand had paid a terrible price to help the British Empire in its hour of need, and the first realisation of how high that price might be was told early in the First World War, in a place called Gallipoli.

I had known the name all my life, but I couldn’t have told you where it was. I knew we’d fought the Turks, but very little else, in the way I knew we’d fought the Boers, and we had died in our hundreds in the trenches of Flanders, but apart from graphic monochrome photographs I had no conception of what and where those things had happened.

Gallipoli is a place apart; it is a finger of land pointing south-west from that small part of Turkey which is in Europe, parallel with the mass of Turkey that is Asian. The deep trench of water between Gallipoli and Anatolia is called the Turkish Straits. It leads from the Aegean Sea, and it is divided into three parts. The first part is called the Dardanelles, that flows into the Marmara Sea, which narrows at Istanbul and becomes the Bosphorus Strait and that in turn widens into the Black Sea. There is a surface current that takes water from the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea, and a deep, cold counter-current that takes water from the Black Sea back to the Aegean.

Gallipoli is a very small piece of land, yet 250,000 Allied forces fought there, along with 280,000 Turkish during a campaign that lasted barely 250 days. The figures are notoriously unreliable, but the maths would indicate that around 2000 men per day were killed or wounded, along a three-part front line that stretched for less than fifteen miles. At times the Turkish front line was only eight metres from the Allies.

We New Zealanders were the British, too, in those days. When I was at school, we learnt English history and British geography. We could see on wall maps of the world the scale of the empire of which we were a part. All that area coloured in red was British and that included us; our grandparents had come from Britain, and the New Zealand and Australian soldiers who signed up in WW1 and WW2 did so for the honour of defending our Homeland. When Britain joined the EU, they cut themselves off from us and put up trade barriers. We had to find our own markets, make our own way in the world and decide who we were, and what was most important to us. The Australians and the British troops, in two World Wars, had called us Kiwis, because of the Kiwi boot polish all New Zealand soldiers were issued. It was a term of friendship, of comradery, and gradually we adopted it over perhaps other choices. It helped that our national bird is also a kiwi.

Our Tour of the ANZAC Sites.

There are five cemeteries of particular interest to the New Zealand visitor to Gallipoli; Chunuk Bair, Ari Burnu, Lone Pine, Hill 60 and Twelve Tree Copse, of which Chunuk Bair is the most important, and there are other places where New Zealanders are buried or memorialised. But before you can go to Chunuk Bair you must pass through ANZAC Cove, as more than 8500 New Zealand troops had to do before you. To start with, the beach is tiny, much smaller than the beach you see in the photos of the 3,100 New Zealanders who landed there on the first day, because the current is removing the beach, pebble by pebble.

ANZAC Cove and North Beach.

There is a little promontory, called Ari Burnu, a short curve of beach, then a short straight before the view widens out onto North Beach and you can see up to The Sphinx, a tall overhang of sandstone that towers above the beach. If you were an ANZAC soldier, at this moment you would be exposed to the full force of Turkish fire over a wide hillside that towered above you. The ANZACs hid behind a low sandstone cliff on a narrow, pebbly beach wondering what on earth had hit them.

The Sphinx from North Beach.

The objective of the first day of the Gallipoli landings was Chunuk Bair. The ANZACs finally captured it in the last few weeks of the campaign, and held it for just three days. It was the only objective of the entire campaign that was attained. When Mustafa Kemal took it back with a huge force, that was the end of the Gallipoli Campaign. The entire force of Allied soldiers had moved barely six kilometres inland.

Elaine and I walked the short distance along ANZAC Cove, the sea licking at our feet. We each picked up a pebble, a little limestone memento before the sea swept it away, and headed back to the assembly point for the ANZAC Day commemoration, a grassy area surrounded by red tiered seating that looked out over the Dardanelles from whence had come the British sea-borne landing for Turkey, one hundred years ago.

“In a few days time, on the morning of the 25th of April,” said Aykut, our Gallipoli guide, “10,500 people will be here to commemorate the ANZAC landing.” He was a stocky Turkish man with intense black eyes, a ready smile, impeccable English and an encyclopedic knowledge of the Gallipoli Campaign. He stood before us in a red jacket, blue jeans and a brown leather hat with a wide brim. He waved his arms over the sea of red seats and the grass at our feet. “You will not find a square foot to stand on if you do not have a ticket. Don’t worry about the seats, this grass beneath our feet will be fully occupied, too. Then, when the first ceremony is over, everyone will join with the Australians at the Lone Pine Cemetery, and when that is over, everyone goes on to join the Kiwis at Chunuk Bair.”

ANZAC Cove is now its official name.

He looked at a new stone structure barely high enough to serve as a seat, with the word ANZAC written in bold bronze capitals. “In 1985, the Turkish government renamed this beach to its wartime name of ANZAC Cove because the Australian and New Zealand governments asked us, and because there is now an Ataturk Park in Melbourne, a plaque in Albany, a plaque in Canberra and the Ataturk Memorial in Wellington. We, too, call this day ANZAC Day. Gallipoli was as nation-building for us as it was for you.”

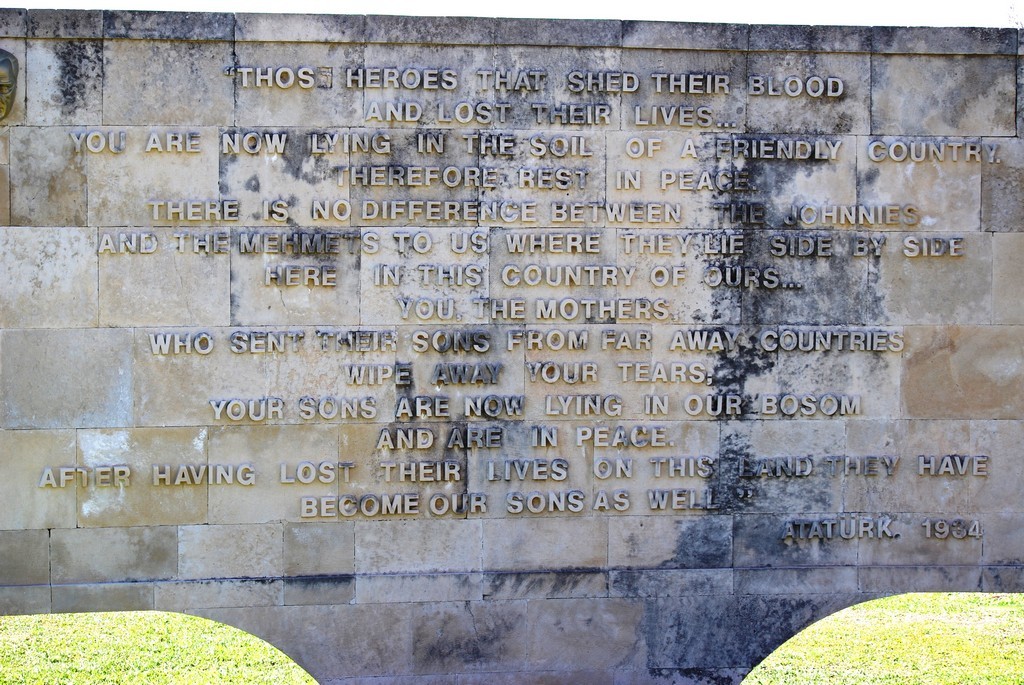

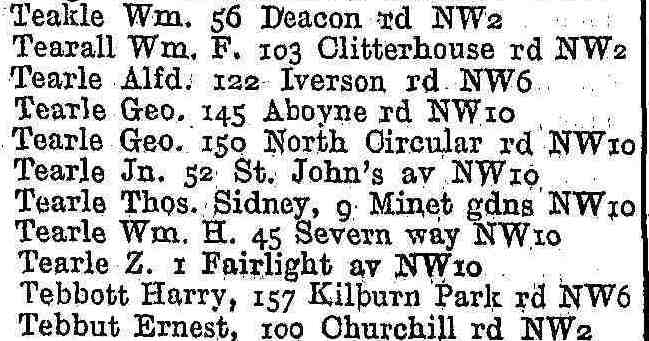

We visited the Ari Burnu Cemetery, just a few metres away. I looked closely at the British-designed sandstone monument beyond the lines of headstones for the first time. It had a wide base and a tall centre decorated with a cross. In the lowest portion of the monument were carved the words “THEIR NAMES LIVETH FOR EVER MORE”.

Ari Burnu Cemetery

Many of the headstones here recorded the deaths of these young men on the first two days of the landing. There were men from the Wellington Regiment, the Otago Regiment, the NZ Mounted Rifles and the NZ Medical Corps. The Australians mostly came from the 2nd and 8th Australian Light Horse. The plaque explaining the cemetery noted that the lines drawn up on the first day of the landings were largely unchanged until the end of the campaign, and that 2000 men died on the first day. The Waikato Times of 22 April 2015 noted that of that number, 200 were from the Waikato, Waitomo and King Country.

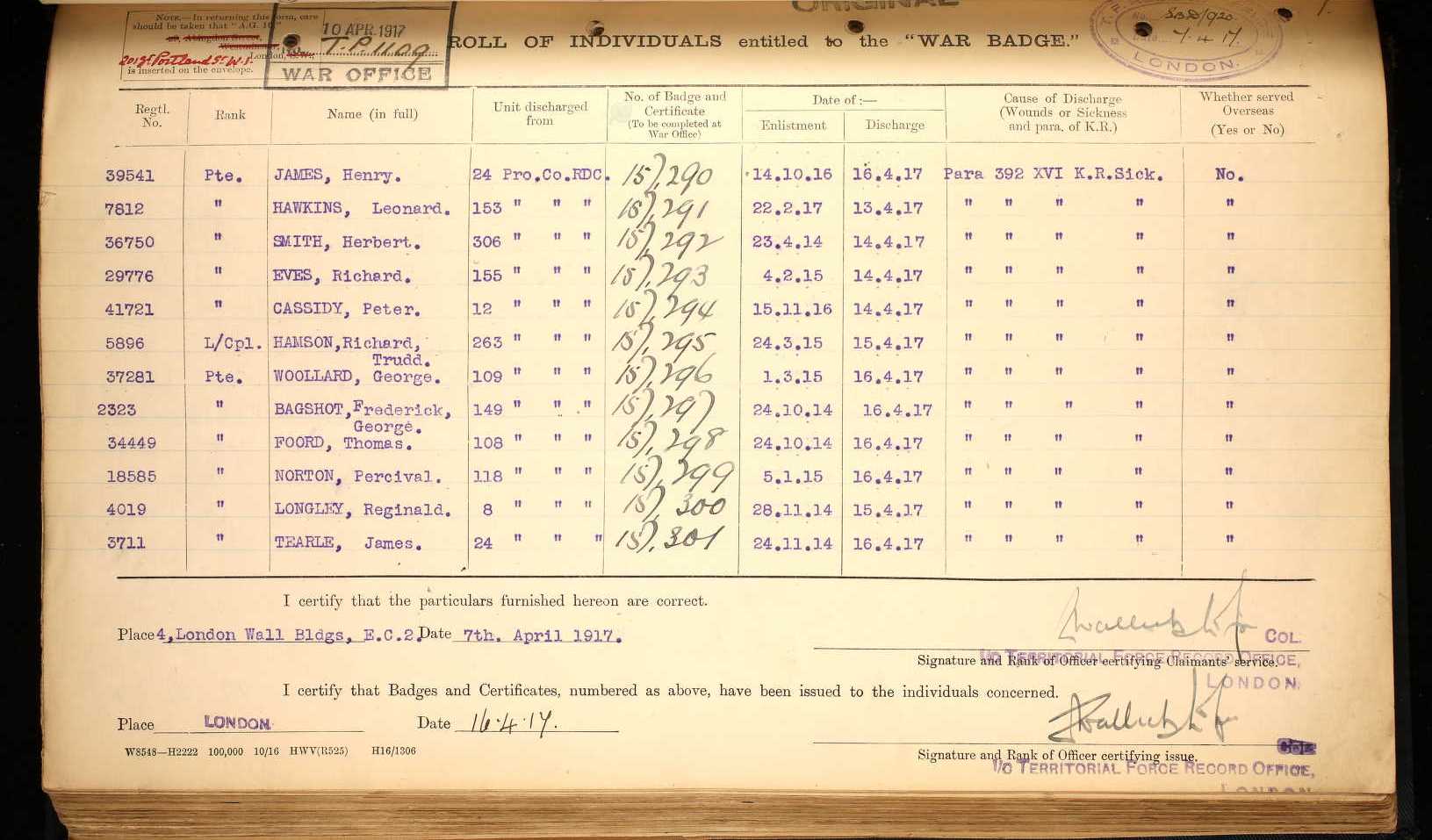

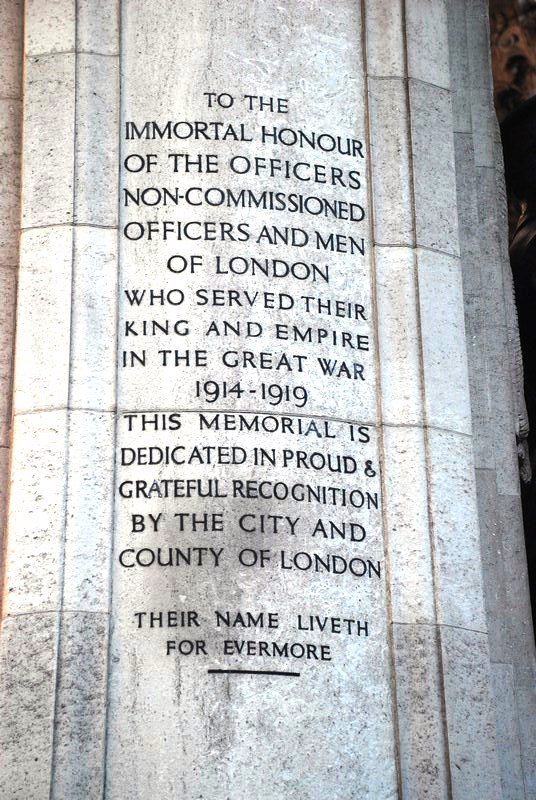

Close to ANZAC Cove was a sandstone monument with raised lettering containing some thoughts written in 1934 from the victorious general, who had become president of Turkey. His name was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk; he was called “the father of Turkey,” hence his name, Ataturk.

He began:

“THOSE HEROES THAT SHED THEIR BLOOD AND LOST THEIR LIVES….

YOU ARE NOW LYING IN THE SOIL OF A FRIENDLY COUNTRY.”

These extraordinary words took my breath away. Whoever heard such sentiments from the leader of a country towards those who had attacked him?

Ataturk’s message at ANZAC Cove.

I wanted to find out if Turks really did feel friendly towards New Zealanders. I had my South African stockman’s hat on and it looked remarkably like a New Zealand soldier’s hat from WW1. The Australian hat was turned up on the left side, so they were easy to distinguish from the Kiwis. If the Turks were actually hostile towards the Kiwis, rather than friendly as Ataturk had declared, then I would soon know, and I would have to stop wearing my hat.

TJ’s bus took us to Lone Pine Cemetery. The shocking thing about the Gallipoli Campaign was how few soldiers were found in order to bury them. Only a hundred or so have marked graves at Lone Pine Cemetery, and a few have “Believed to be buried here” headstones. The rest of their names, 4,222 Australians and 709 New Zealanders, are on wall plaques, some cut stone, and some engraved brass. Plaque after plaque of closely-packed names, usually organised by regiment, battalion and rank. A lone pine does exist; a plaque reminded us the existing pine was grown from a seed of the original. The monument has a remembrance book which we signed “To our Australian cousins, because we promised never to forget.”

Lone Pine Cemetery.

The next stop was Chunuk Bair. Only a few bodies were found, and we counted just ten headstones, all New Zealanders.

The ten NZ graves on Chunuk Bair.

There were again the serried ranks of names on plaques, of men who served in the Auckland Regiment and the Wellington, Christchurch and Otago Regiments, as well as some who served with the NZ Navy and the Medical Corps and the Wellington Mounted Rifles.

Wellington Mounted Rifles names on Chunuk Bair.

This photograph came from Elaine’s collection of photographs and includes the name Lance Corporal L M Natzke.

A huge bronze of Ataturk with a tall flagpole towered over the NZ memorial, one arm across his chest holding his binoculars, and the other holding a swagger stick behind his back, as befits the victor.

Ataturk guards Chunuk Bair.

Recently recut trenches traced the lines down which Turkish forces and their supplies moved.

The trenches on Chunuk Bair.

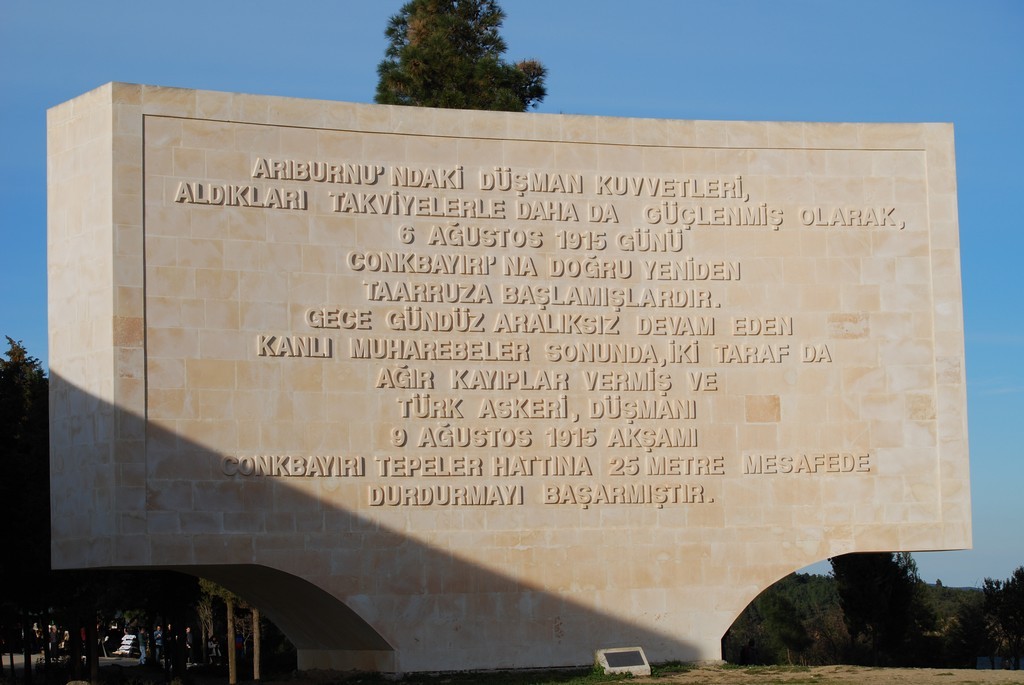

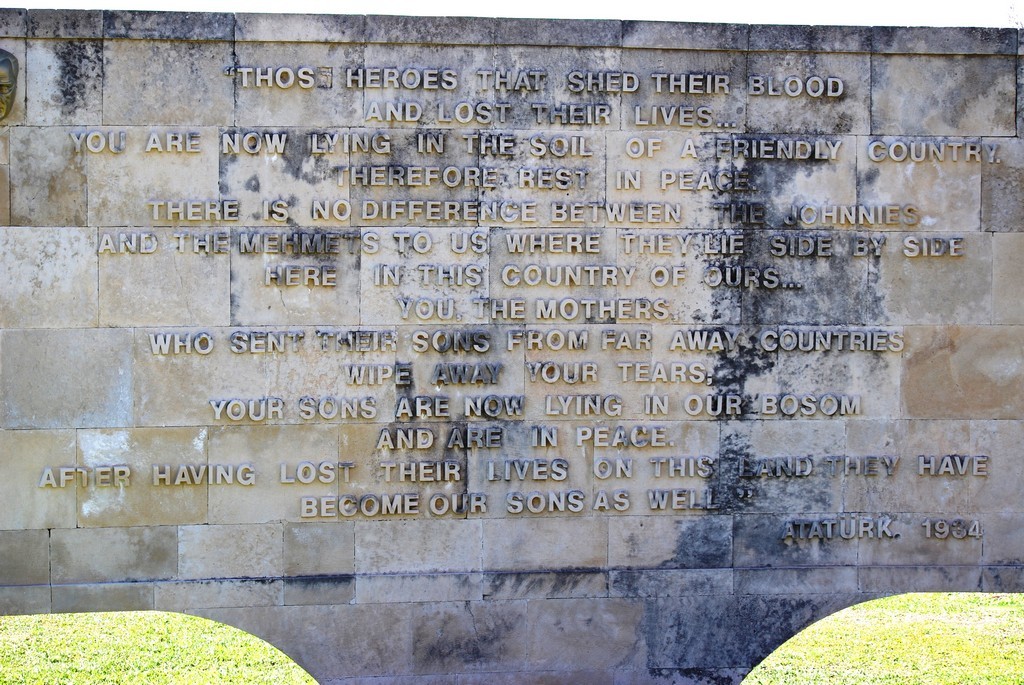

In a large clearing on the hilltop, four huge curved stones told the story of the Turks of Chunuk Bair on significant days in their desperate struggle to keep their country.

The ANZAC assault of 6 August is repulsed.

The plaque with the translation of the 6 Aug 1915 assault.

One look over the brow of the hill to the land below was enough to show even the casual onlooker of the huge advantage the occupation of the top of the hill had for those who could keep it. Stripped of its vegetation, the view down the hill to those trying to climb it was panoramic and clear. No-one could move without the lookout seeing it, and the field of fire was almost total. For that reason, many of the most important troop movements in the campaign had to be completed during the night, with understandable confusion over battle orders, due to units becoming lost in the darkness.

The view from Chunuk Bair.

Hill 60 Monument.

We moved on to the Hill 60 Cemetery. The bus pulled over on a straight stretch of road and the driver pointed to a dirt track just wide enough for an SUV, but not for a bus. The sign on the side of the road pointed the way to Hill 60, almost directly in line with Chunuk Bair high on the horizon. To its left as we viewed it, and 20m higher, was the rounded dome of Hill 971.

The cemetery marked the last major assault of the Gallipoli Campaign. In eight days 788 Allied soldiers were killed, for no real gain. Of those soldiers, 182 New Zealanders have no known grave.

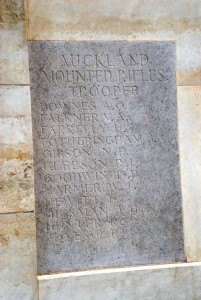

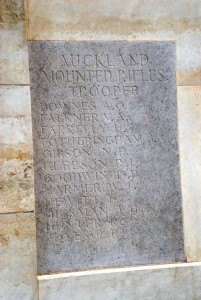

We walked up the track. Hidden behind the bushes that overhung the track was the now familiar form of a British memorial, enclosed in a field barely a third of an acre in size. We were looking specifically for a Richard Roland Jones, whom Dos Mark of Otorohanga had asked us to find. Elaine had found him listed with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and finally here we were. None of the surprisingly few headstones mentioned him. Elaine said that Dos’ grandmother’s brother was never found; he probably did not have a headstone. She found his name on the memorial itself in the Auckland Mounted Rifles: Trooper Jones R. R.

Jones R. R. the last name on the Auckland Mounted Rifles Hill 60 Memorial.

Jones R. R. closeup.

Our last visit to the ANZAC sites was to Twelve Tree Copse, where 179 New Zealanders are recorded. They were killed in the Second Battle of Krithia and on the Helles front during May and July 1915 and “whose graves are known only to God.” No-one else was visiting the site, and Elaine and I photographed some New Zealand and Australian headstones. The writing on the now familiarly shaped memorial was fiendishly difficult to read in the available light.

The memorial at Twelve Tree Copse.

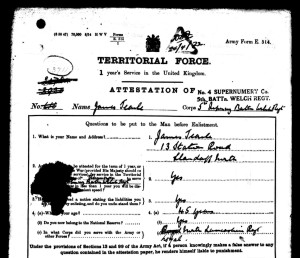

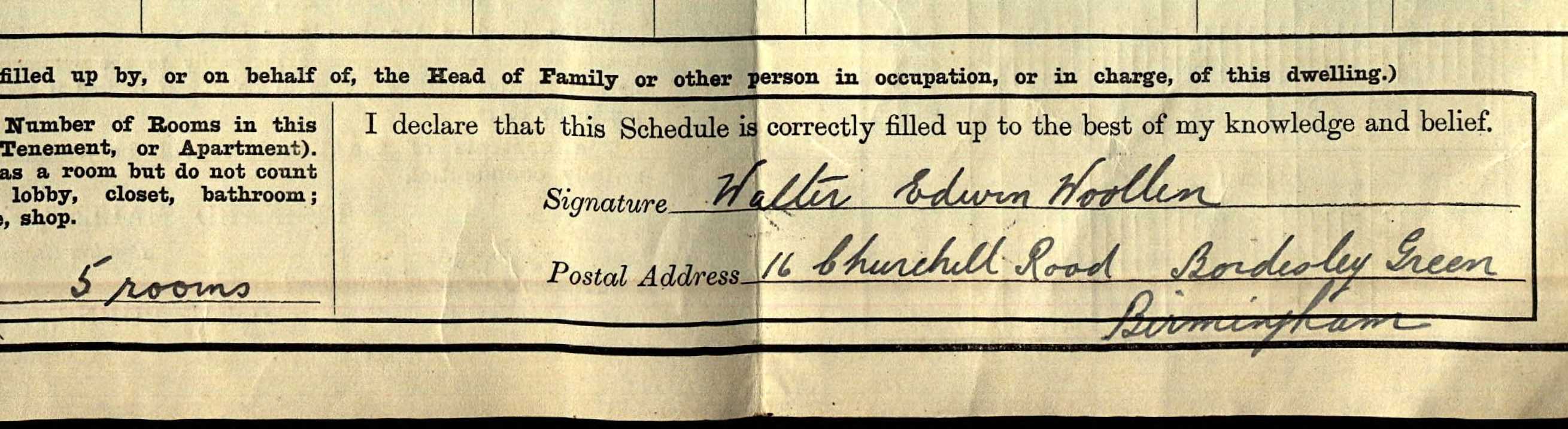

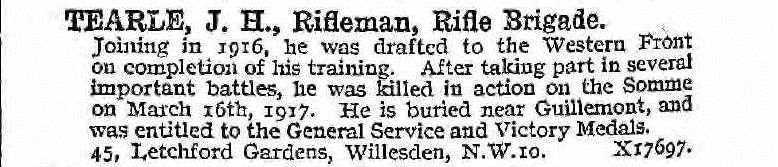

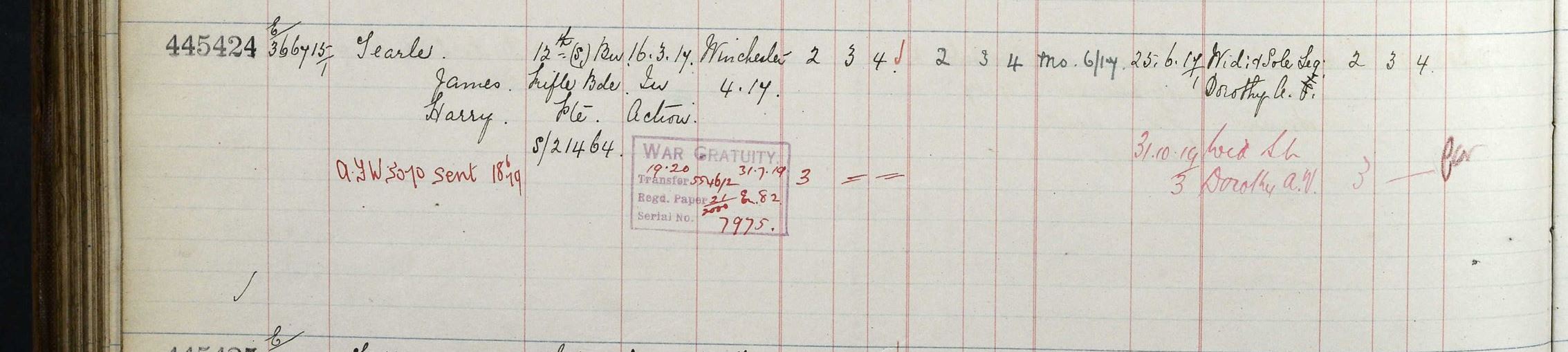

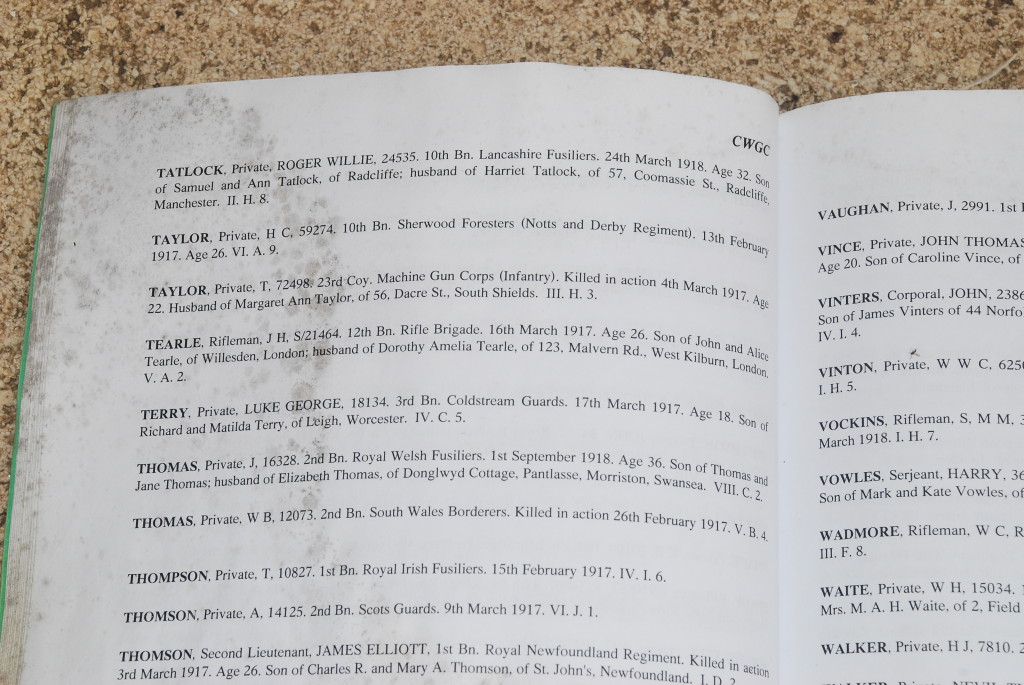

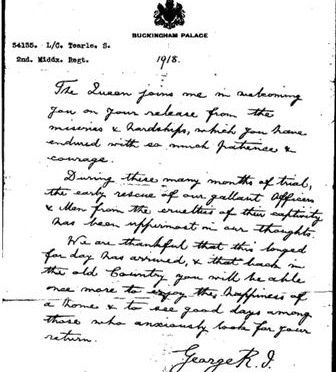

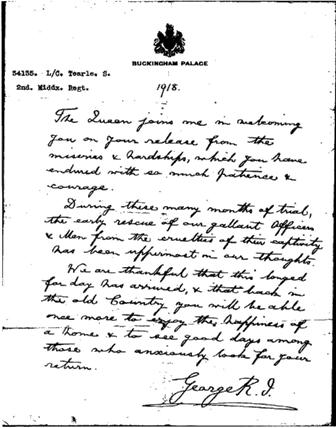

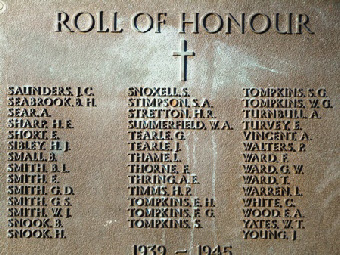

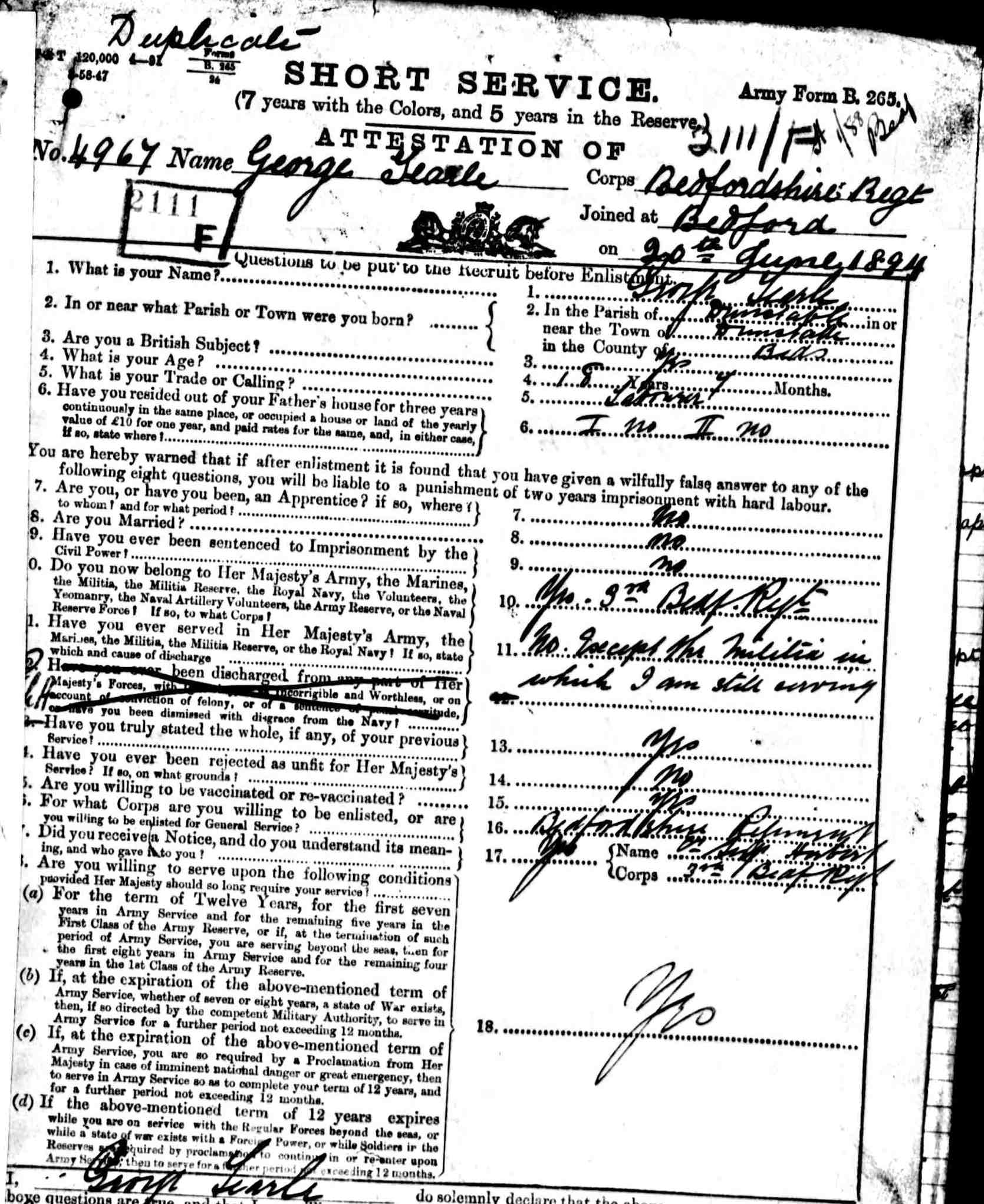

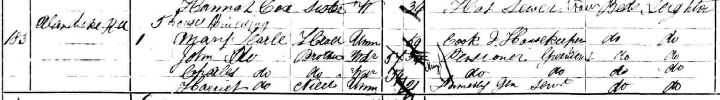

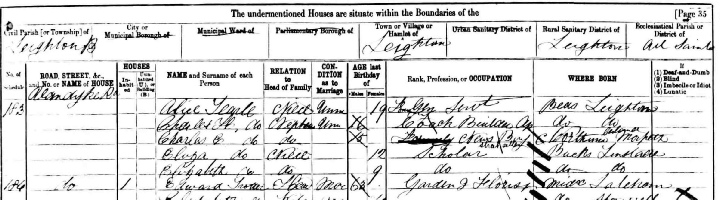

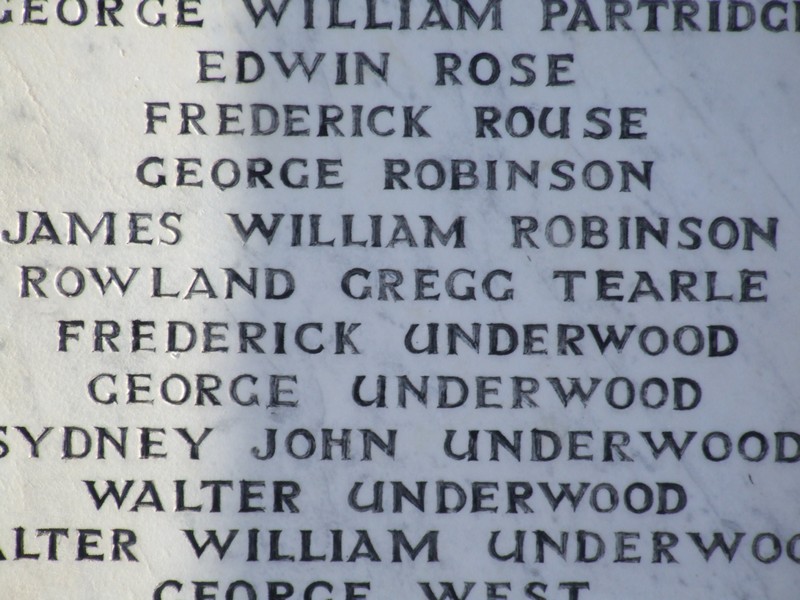

John Henry Tearle – The Hertfordshire Soldier

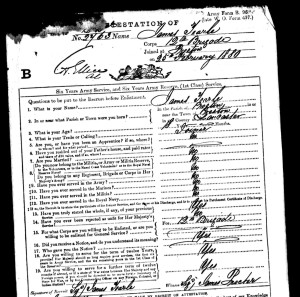

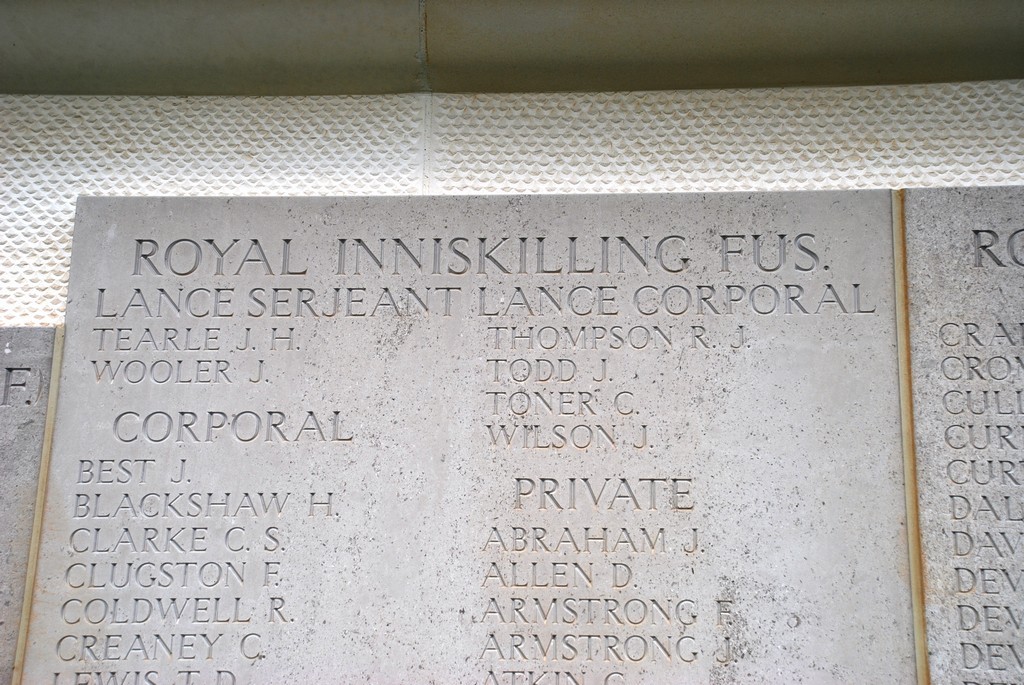

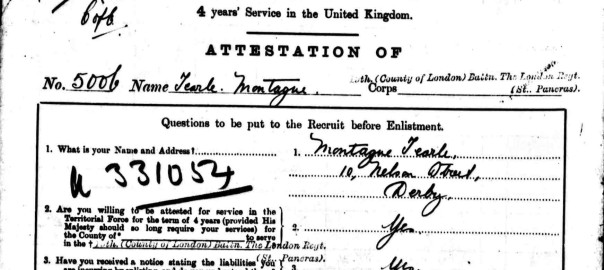

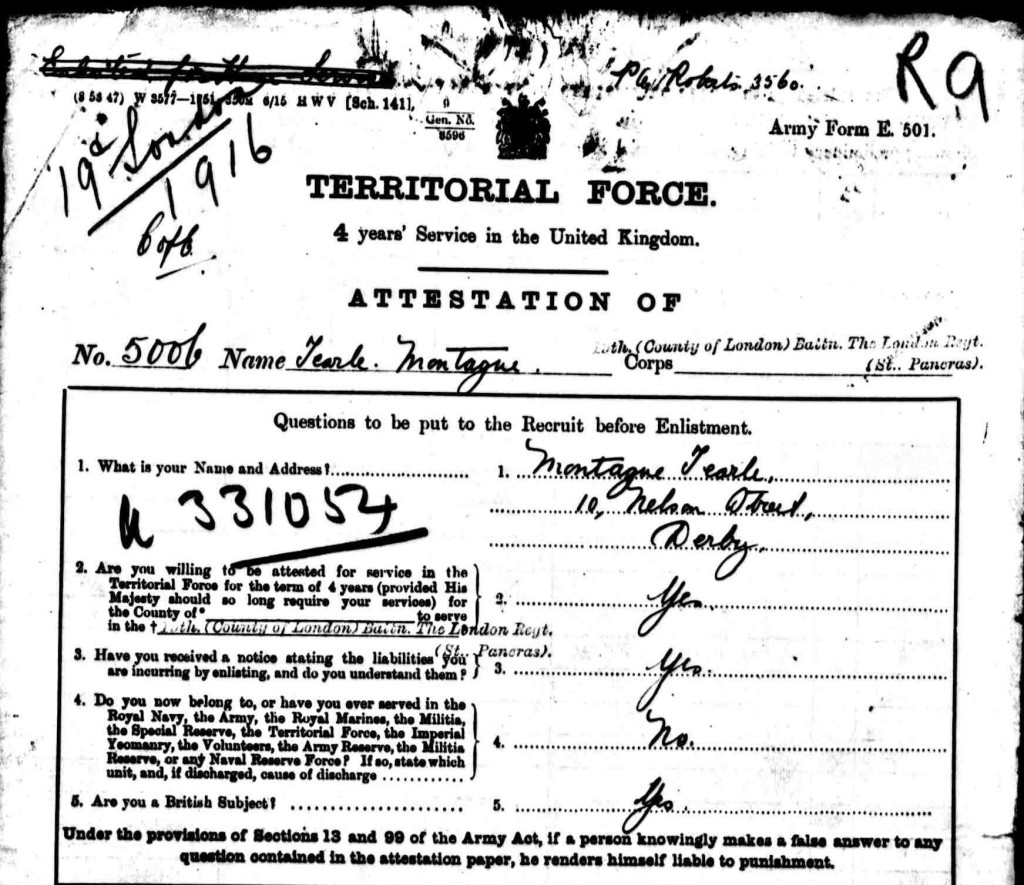

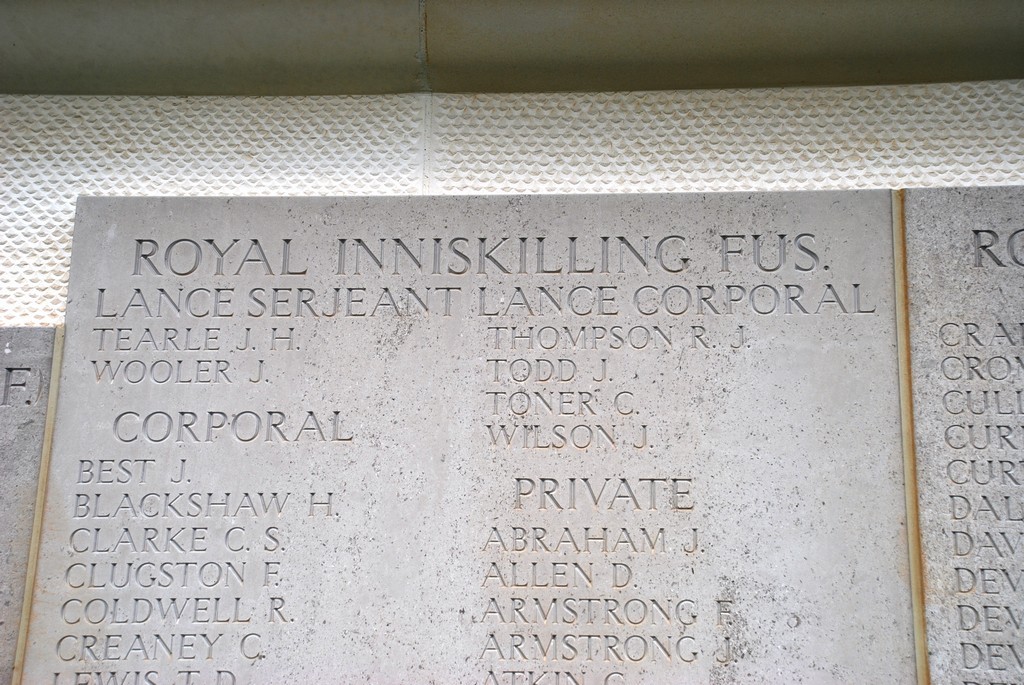

“Do you know anyone who was killed at Gallipoli?” our friends would also ask. Indeed I did, and he was the main reason I wanted to go to Gallipoli. His name was John Henry Tearle, from Hertford, a lance sergeant in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. His name was on the Helles Memorial because he was fighting in a British Regiment. It may seem odd these days, but before 1922, all service in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland was called Home service and did not count for service medals or pension. John Henry was not fighting for or even with the Irish; he was fighting with the British. The Inniskilling Fusiliers were recruiting in Hertfordshire, so he joined them. The irony was that because he did not join the Hertfordshire Regiment, his name is not remembered anywhere in Hertfordshire as a Great War soldier and casualty.

Port Hill Bengeo – last terrace on right, now part of number 69.

Elaine and I had visited John Henry’s home in Bengeo, a short climb up a steep hill that looks down on the A414 as the highway snakes its way through the heart of Hertford. The house was an end terrace with a door and an upstairs window. It probably had no toilet and no running water. John Henry, his sisters Florence and Jane, and his grandmother Harriet Tearle from Soulbury, in Buckinghamshire, were so poor, they had spent time in the Hatfield Union Workhouse, as late as 1896. I think he thought that working in the army would at least give him a paying job. He was reasonably successful, too; lance sergeant was a good few steps up the ranks. Notice of his death on Gallipoli at only twenty-eight years old, was given to his mother, still resident in the terrace house pictured above. Large numbers of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers had died with him.

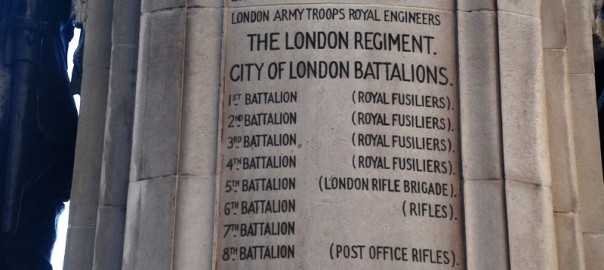

The Helles Memorial.

We arrived at the Helles Memorial, which was a beautifully built sandstone obelisk towering over the landscape and giving a view over the Dardanelles. On the map we had, it was called the Ingiliz Helles Aniti. A sign said that this memorial has the names of 25,000 servicemen who died in the Gallipoli Campaign. We three were the only people visiting it. After the busy scenes at the other memorials, it was a shock to realise that no-one seemed to know that so many young British soldiers had given their lives, and they had been forgotten. We were pleased we had come.

I gave Aykut the envelope containing everything I knew about John Henry – the photos of his house, his short military record, the file from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the plan drawing of the memorial – and he studied them all closely. He went off towards the near wall of the monument and stopped at the far end. He looked towards me and said nothing. He had found John Henry. He moved off when I arrived and I stood, head bowed for a short while, and paid my respects.

“He died on 29 June 1915,” said Aykut, when I joined him. “He would have been fighting in the Battle of Gully Ravine. It was very hot. It always is in June. The battle was on 24-28 June, so he would have died of his wounds.”

John Henry Tearle on Helles Memorial.

“If he died of his wounds,” I queried, “wouldn’t he have been buried? He is on this monument because he could not be found and buried.”

“He only had to be in a field hospital a few hundred metres from the front and if there was a delay of just a day or so to get his body to a more rearward position, then he would have been left behind, and he would never have been found and identified.” He paused. “So his name is on the memorial. Most of the men killed on Gallipoli, Allied and Turk, are still lying in this earth, unknown and unidentifiable.”

The Turkish Heroes

In order to inspire their troops, a nation needs heroes; ordinary men who did an extraordinary thing. There are two who stand out above all else. One is recounted by General Casey, who became Lord Casey, Governor General of Australia. An English officer lay wounded in the no-man’s land between the Turkish and British front lines. The fighting was fierce, and no-one dared to leave their trench to rescue the officer. From the trench in front of them, someone waved a white flag and after a moment, a Turkish soldier stood up, climbed out of his trench and walked towards the English officer. He calmly picked him up, and to the astonishment of all, he carried him to the British trench and handed him down to the waiting men. The soldier walked back to his own trench and jumped in. There is a huge statue near ANZAC Cove of a Turkish soldier carrying an English officer. The soldier’s name was Mahmetcige Saygi. For such gallantry on the battlefield, may his name live forever.

Mahmetcige Saygi and the English officer

The second ordinary man was a gunner in one of the 12 forts the Turks built to guard the Dardanelles. His huge nine-inch gun had been firing at British warships all morning, and it was struck by a shell from the naval bombardment, destroying the crane that carried live shells up to the gun’s breach. Corporal Seyit Onbasi carried three 275kg shells up the ladder to the gun. “One of those shells hit the rudder of the battleship OCEAN,” said Aykut, “and she drifted onto the mines guarding the shore, destroying her.”

“Two hundred and seventy-five kilograms!” I exclaimed. “That’s an enormous weight.”

“All done on pure adrenalin,” said Aykut calmly.

Cpl Seyit Onbasi carries the shell to his gun.

The Turkish Memorials.

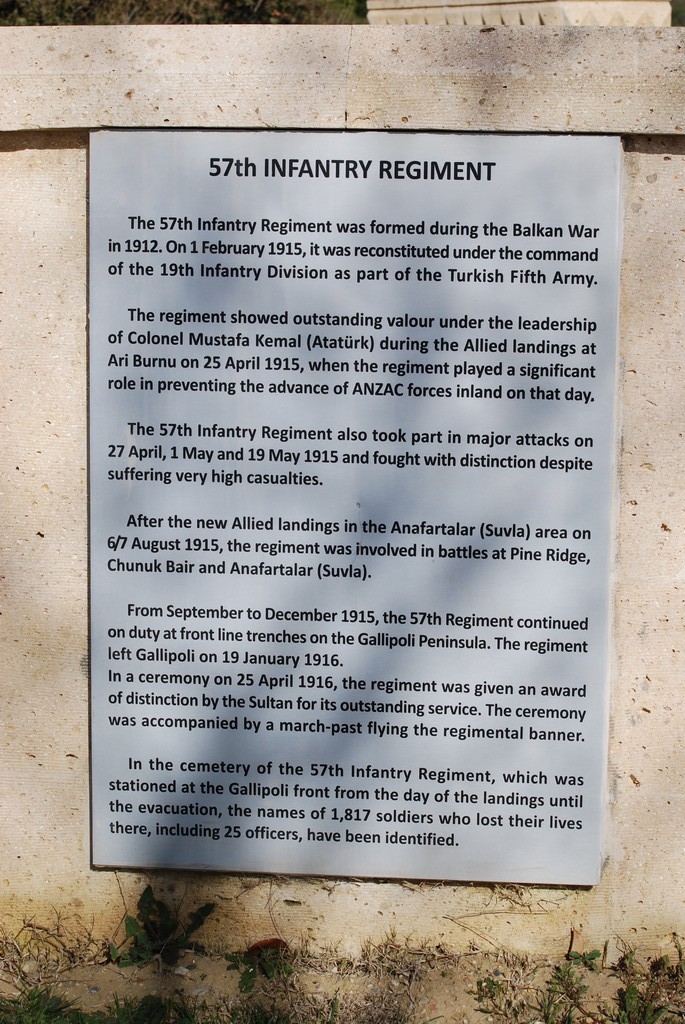

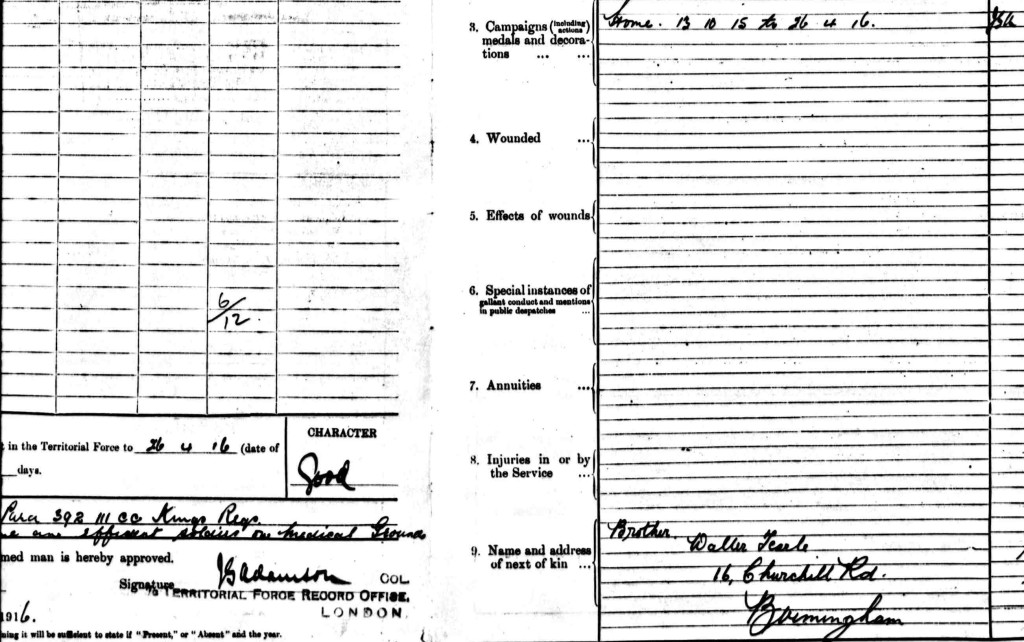

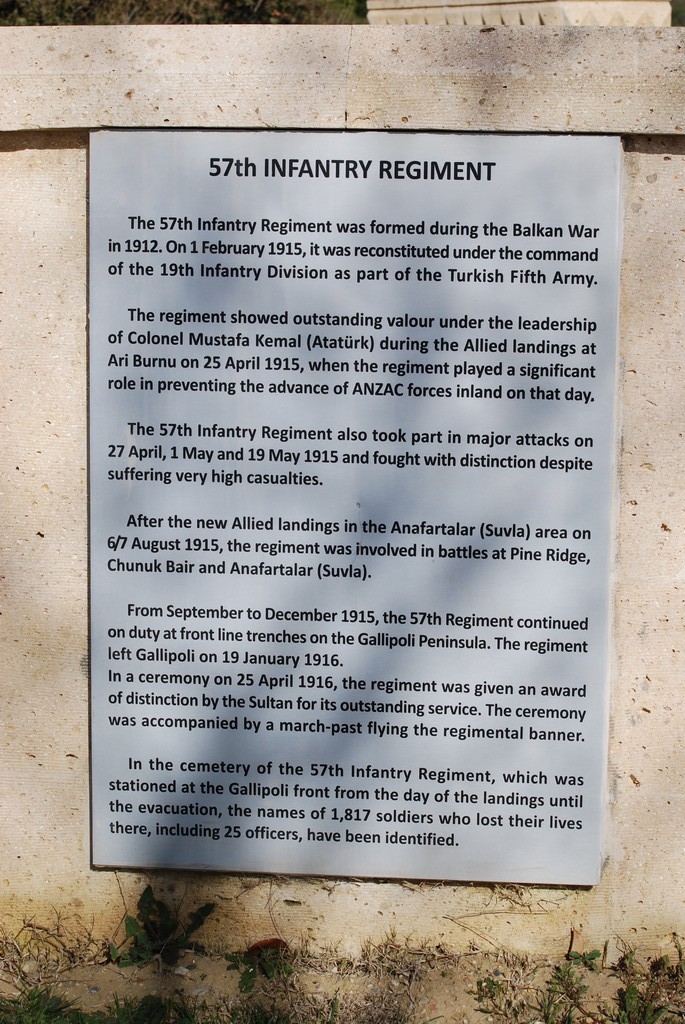

A three-times lifesize bronze of a Turkish soldier with a bayonet attached to his rifle guards the carpark and market of the cemetery for the 57th Infantry Regiment.

A soldier of the 57th Infantry.

It is famed nationally for two reasons; this was Ataturk’s regiment, and it won the Gallipoli Campaign, having fought on the peninsular for the full length of the war.

The plaque detailing the acts of the 57th Infantry.

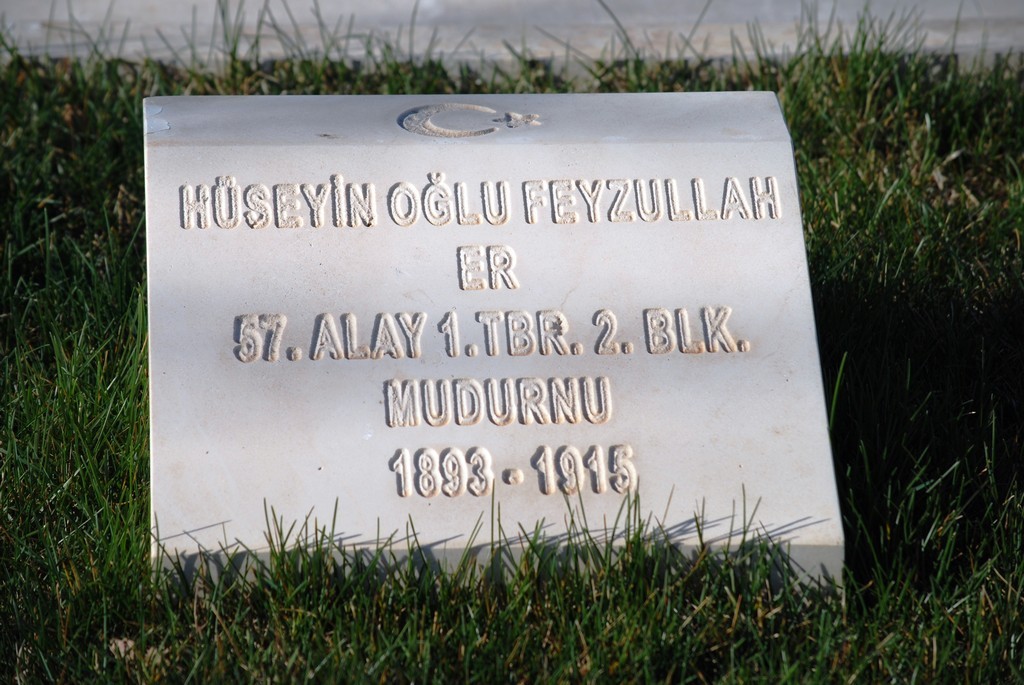

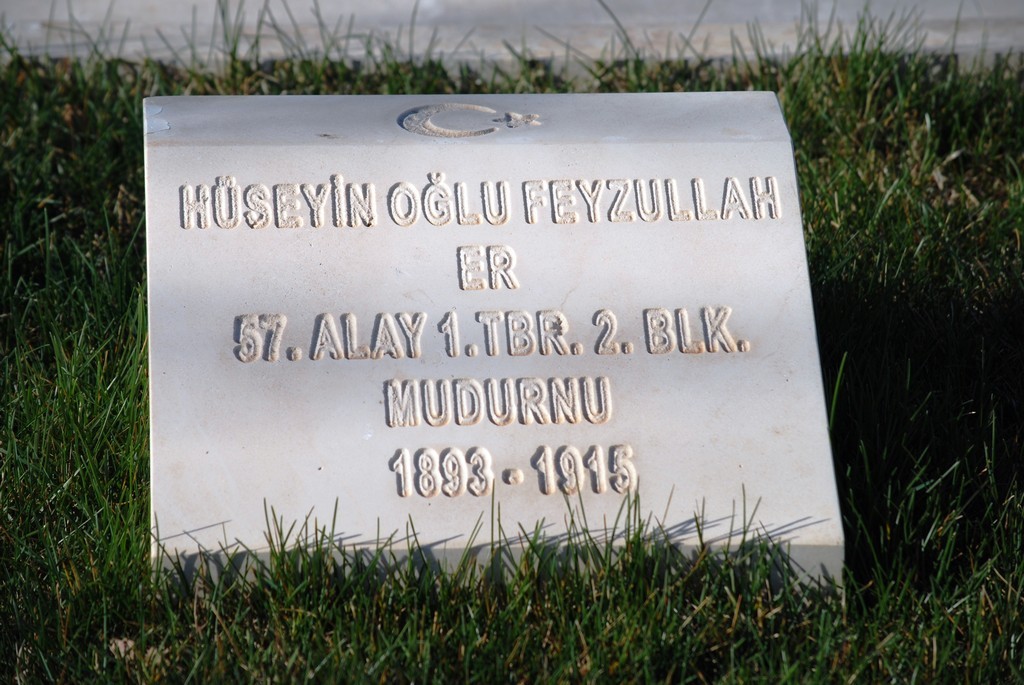

The headstones lie in ordered ranks along the hillside, but Aykut warned me that they marked no grave.

A headstone for a soldier of the 57th Infantry.

“All those who were recovered are buried in a mass grave to the right of the memorial,” he told me.

“A mass grave,” I repeated slowly. “The dead soldiers were each rolled into a shroud and lowered into a pit, side by side.”

Aykut nodded.

“And then earth was spread on them and another layer was added?”

He turned sadly away. “The names of those in the mass grave are written on stainless steel pillars lying on the ground at the bottom of those steps.”

He indicated a set of honey-toned sandstone steps behind me. I turned and followed them, busy with visitors, down to see the names. I stood shocked at the scale of the disaster.

Turkish names at the Memorial of the 57th Infantry.

On the way back I met an old man working his way slowly down the steps and I wordlessly took his elbow to ensure he didn’t fall. He stood and looked at the silent memory of so much death and breathed a deep sigh. As I helped him back up the steps he said, “Where do you come from?”

I said “New Zealand,” but it meant nothing to him. “Kiwi,” I tried.

He broke into a smile, “Ah! Thank you! Thank you!” He shook my hand, and a younger man took over and led him gently towards the steps leading to the memorial, where hundreds of people were viewing the magnificent spectacle and quietly checking the names on the headstones.

Gateway to Kesikdere Sehitligi – the memorial to the 57th Infantry Regiment.

I was browsing the market in the car park when a young woman in a formal black suit stopped beside me and asked me where I came from. She said she was from Turkish Television, and at the foot of the Turkish soldier, she and her cameraman interviewed me on why I was in Canakkale. I don’t know if it was ever aired.

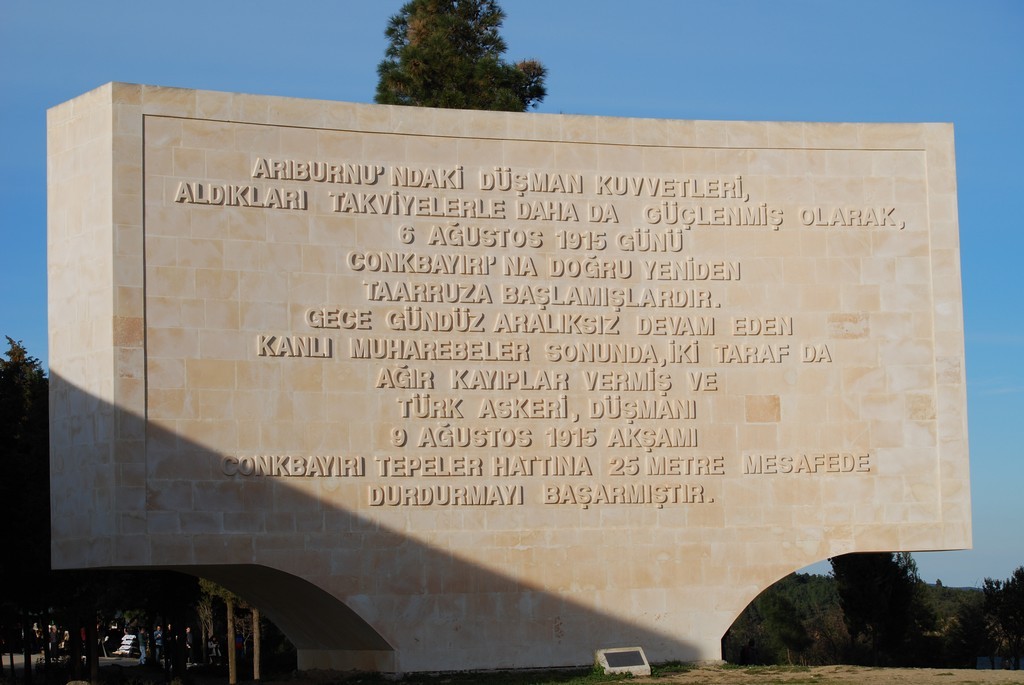

The second great memorial is in Helles, not far from and in plain view of the English memorial where we had found John Henry’s name. It is more than 41m tall and it is called the Canakkale Sehitler Abidesi. It is the national symbol for the Gallipoli Campaign, in the same way that Chunuk Bair is for us. From the bus park we walked past a plaque with Ataturk’s 1934 message to all those who had died, slightly different in wording from that at ANZAC Cove, but obviously a translation of the same document. For the next hundred metres of the walk through tall pine trees, there were row upon row of glass pillars with perhaps a hundred names engraved on each of them. “64,000 Turkish soldiers are listed here,” said Aykut.

64,000 names of the Turkish National Monument to the Canakkale Campaign.

We walked towards the impressive monument, and noting that no-one was walking on the grass towards it, we followed the track beside the trees that showed the way.

Turkish National Monument to the Battle of Canakkale.

As I arrived close to the monument, at the top of a few stairs were four men who looked long and hard at me. I stopped and lowered my camera, in case they thought I was photographing them.

“Where are you from?” asked a man wearing a cloth cap, who stood in the middle of the group. All of them were much shorter than me, and had thick, heavy overcoats and grey moustaches. “New Zealand,” I offered tentatively.

“New Zealand!” shouted one of the group. He turned excitedly to the others, who had gathered around him. “Kiwi!,” he shouted. They all turned round, ran the few paces to me and surrounded me. The short man pushed his camera into my hand. “Photo,” he said. I sat my camera down on the grass nearby, took the man’s camera and photographed the men standing proudly in front of their national monument. The short man came back to me, “Photo,” he cried. They stood either side of me and put their arms over my shoulders. The fourth man took a photo. They changed places and took another photo, then another, and another, to ensure each man was in a photograph with the Kiwi. It was a wonderful experience. I picked up my camera and shook hands with each man in turn, grateful to be accepted, as Ataturk had intended that I should be. I had learnt a great deal about the Turks.

I continued towards the monument, trying to fit its massive size into a single picture. I saw a bas-relief of Corporal Seyit Onbasi again, photographed it and then walked up a few steps into the bulk of the building. Three young Turkish lads crowded around me.

“Where are you from?” The tallest of the three, perhaps as young as 17 years, with a sallow complexion and close-cropped hair, looked at me intently.

“Kiwi,” I said, missing out the formality of country.

“Kiwi!” They yelled in unison. They sat on the steps in front of me. “My name is Kagan,” said the tall one, solemnly. I wrote the word in my diary. “Nice name,” I said. “I’d like a name like that; it has a ring about it.”

“This is Emir,” he said with a smile, waving his hand to his left where sat a younger boy with long dark hair. “And this is Utku,” he said motioning to the young Turk in a brown sweatshirt on his right. I checked the spellings with each of them, wondering why they wanted to introduce themselves. The crowd of visitors swirled around us noisily. “Why are you here?” he asked.

I pointed in the direction of the Helles Memorial for the English, “I have visited a member of my family whose name is on that memorial.” I paused. “Why are you here?”

“Because it will be the 25th of April.”

“And you call it ANZAC Day. So do we.” If he was worried about the differences between us, they vanished.

“Selfie, selfie,” said Kagan, standing tall and beaming broadly. He produced his smartphone and took a quick snap of himself with me. “Me too, me too,” cried the others and they crowded even closer.

“Can I use your hat?” Kagan asked. I gave it to him and he gleefully pressed it down onto his head. I thought, what have I done? Is that the last I have seen of my hat? He lifted the smartphone again and dropped his arm around my right shoulder. I could hardly move. He was pressed against the stone pillar and I was pressed against him by Utku; his arm was draped over my left shoulder.

“Me too, me too!” Emir’s long black hair pushed under my arm, between my chest and Kagan, his dark brown eyes shining with excitement as he looked up to make sure he was in the shot.

“And me, and me!” A pretty blonde girl whom I had not noticed at all, with a swirl of green something – a jersey or a blouse or a skirt – flung herself onto the step in front of me and knelt down to see herself in the smartphone. Kagan took the selfie two, perhaps three times, to the delight and high amusement of everyone in the vicinity. They all stood up. Kagan took off my hat and gave it to me. I dropped it on my head. He was laughing and crying and showing the picture he had taken to anyone who wanted to see it. He turned back to me, stopped smiling, and held out his hand. “Thank you, thank you,” he said solemnly. He shook my hand with both of his and then each member of the group did the same, including the girl in green. I was very, very impressed with the Turks.

Some Explanations

The Turks do not refer to Gallipoli, the word is an anglicisation of Gelibolu, the Turkish name for this peninsula, so the word means nothing to them; they refer to this battle as the Canakkale Campaign, or the Battle of Canakkale. The word is pronounced Chen-ark-alay, with the stress on the middle syllable. The name is everywhere, and Aykut pointed out that Chunuk Bair (bair is a hill) is actually a corruption of Canakkale, and should say Canakkale Bair; the hill from which you can see Canakkale. The town itself is on the other side of the Dardanelles, directly opposite Eceabat.

Lifesize tableau of life in the trenches – found in Eceabat.

While we were in Eceabat, and again while staying in Istanbul, we saw an incredible number of ships passing by or at anchor, and being joined by more with every passing hour. Many of these ships would put WW1 battleships into frigate size in comparison, but every now and again we would see a ship so large it dwarfed everything in sight. Even then, this gargantuan vessel was still travelling in excess of twenty knots. When you see this volume and majesty of shipping in the Dardanelles, and in the Marmara Sea, waiting their turn to proceed, then you appreciate what the Turks were fighting for.

When we visited Chunuk Bair, I was late for the bus and Cemal came looking for me. She was perhaps twenty-five years old, quite tall, with long dark hair framing a serenely beautiful face highlighted by deep, dark eyes in a honey complexion. She had a red leather jacket over a blue jersey and shiny new Spanish ankle-boots. She had joined us from Eceabat and she had told us on the bus that she was attending two universities, one to study public relations and the other to study Turkish. She wanted money to pay for her tuition, and she wanted to improve her English, so now she was also a trainee guide, learning her country’s history at the same time. It was clear to her I was not heading for the bus.

“Where are you going?” She asked. I pointed through the trees to the huge Turkish stones with the stories on them and we threaded our way through and over the trenches that had been cut into this hilltop by an earlier generation of young men of about Cemal’s age.

“There is a big worry in our country that the government is removing all the changes that Ataturk made for us,” she said. “This is a country where everyone is a citizen and there is no special treatment for any religion.” I recognized the definition of secular. “But the government is passing laws to change that. Ataturk would not have liked it.” She paused as we were about to jump a trench. “I have a tattoo.”

I stopped my headlong flight to the stones. “A what?”

Cemal’s tatoo

She rolled up the sleeve on her right arm. “It is Ataturk’s signing. He is my hero.” On the clear white skin of her forearm was indeed Ataturk’s signature. “Everyone who wants Turkey to be governed as a modern state has a copy of this somewhere so people can see.”

“A tattoo?”

“No, the writing might be on their car, or on their house. We love our country; many, many young men died for it and they died for Ataturk. We want our country to go forward as Ataturk wanted it to.”

Her earnest vision was clear and beautifully expressed. Elaine and I had received nothing but good will from all the Turks we had met. I hope that in a troubled world, she, and her country, manage to negotiate the churning seas that lap at its shores.

Update

The New Zealand Herald of 14 April 2015 reported that Wellington and Canakkale had signed a sister city relationship. The Turkish ambassador to New Zealand, Mr Damla Yesim Say noted:

“All the fallen in Gallipoli are our grandfathers, and we are proof for posterity that people who once fought as enemies can proudly stand shoulder to shoulder today in remembrance of their grandfathers’ sacrifice, and in celebration of their friendship.”

Some figures

Elaine and I are from the Waikato and the Bay of Plenty respectively. From the towns and villages with which we are most familiar, here are some figures of the fatalities of World War 1, printed in the Waikato Times of 22 April 2015:

Hamilton 222

Morrinsville 10

Otorohanga 58

Paeroa 3

Piopio 19

Te Kuiti 30

Waitomo 1

“A few over 100,000 New Zealanders sailed to join the First World War. Of those 18,000 were killed and 40,000 were wounded.”

In 1914, the total population of New Zealand was 1.1 million.

Post Script

Elaine and I stayed in Istanbul for more than a week and visited the ANZAC sites of Gallipoli during April 2015, the centenary of the ANZAC landings, to discover the relationship we had with the momentous events of the Gallipoli Campaign. We found family members who had died there, and we found men from other families whom we hadn’t expected to come across.

What we never anticipated was the unabashed friendship that was extended to us when ordinary Turkish people met us and realised we were Kiwis. I told three stories above that illustrate this, but there were many, many others.

Our stay in Turkey was a revelation, and my one of my objectives in publishing this story is to express our deep gratitude to TJ’s Tours of Eceabat and his staff who worked tirelessly to ensure we were given every opportunity to explore Gallipoli to the fullest extent possible in the time we had.