Bristol Beaufighter in the RAF Museum, Hendon. (Photo, Elaine Tearle)

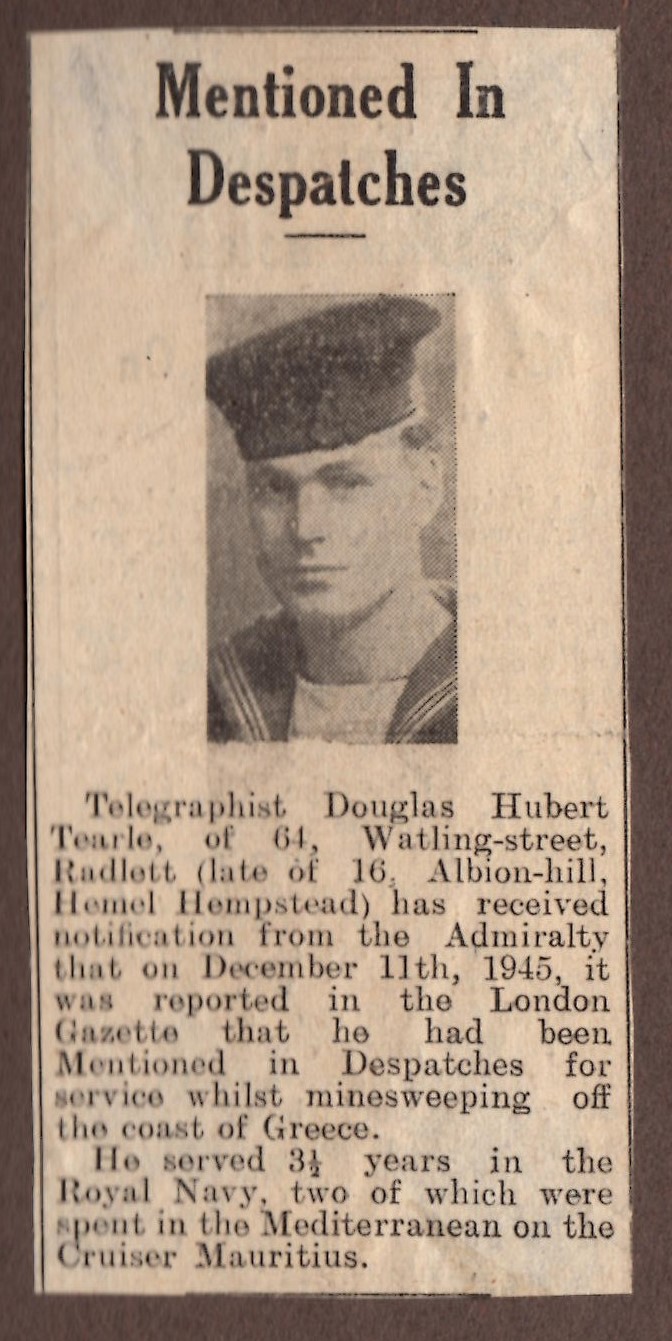

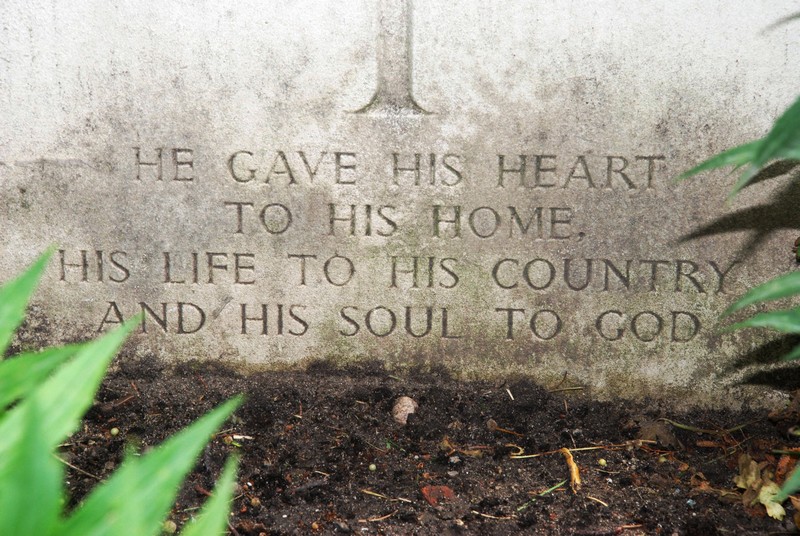

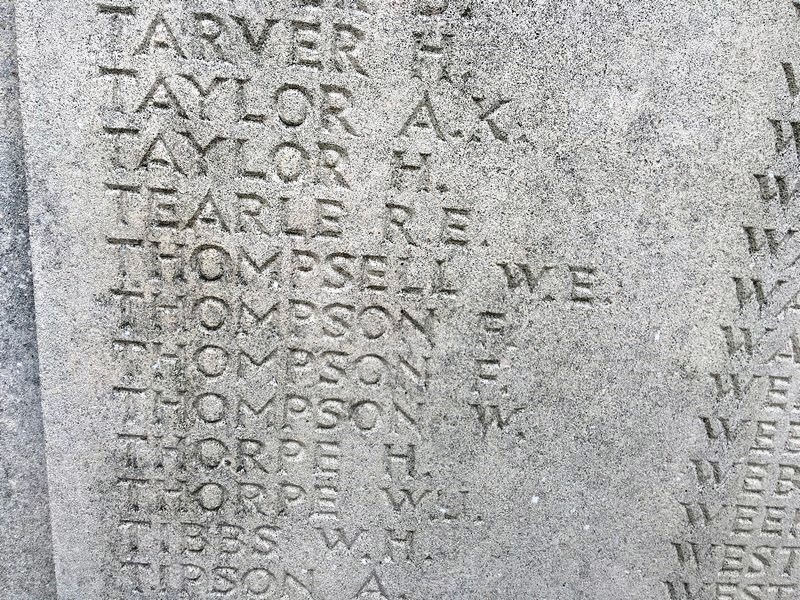

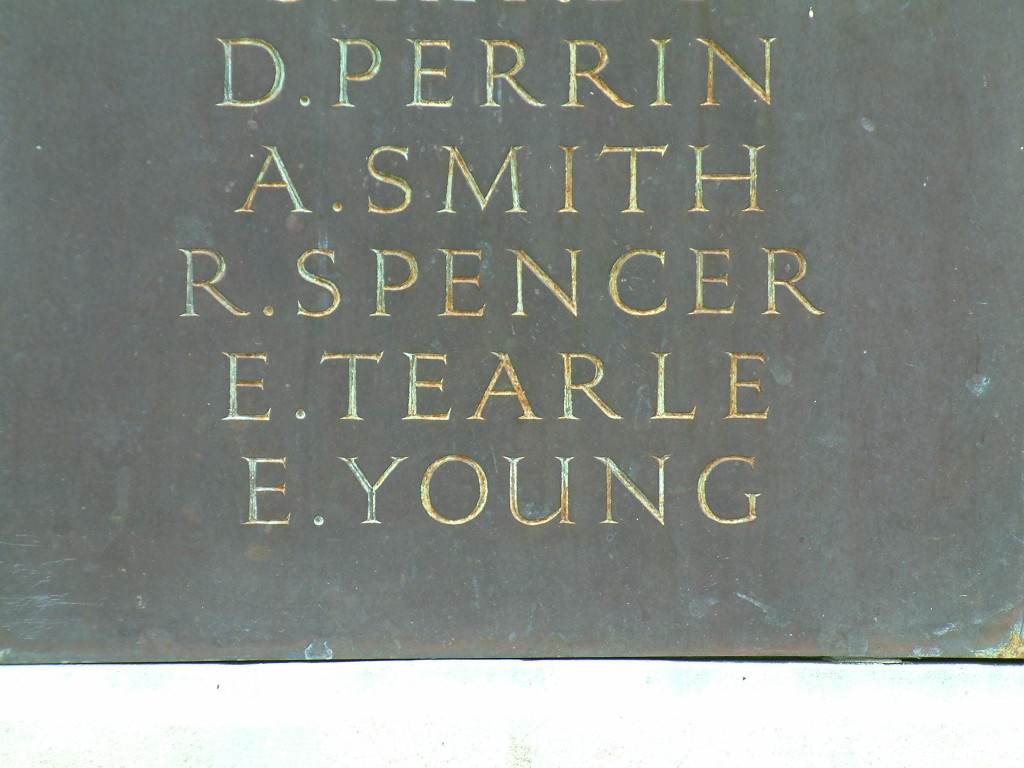

I became aware of the Bristol Beaufighter because of the story I wrote on Sgt Francis Joseph Tearle, whose name I found on the Battle of Britain memorial outside Westminster tube station in London. As a post-WW2 child I grew up on stories of Spitfires, Hurricanes, Mosquitoes and Wellington bombers, but until this year (2016) I had never once heard the name Beaufighter. During my research for this article, and in my travels on the trail of Sgt FJ Tearle, who flew the plane in Malta, I have developed an affection for this beautiful, destructive and highly dangerous airborne weapon. My source for all things technical is Jerry Scutt’s Bristol Beaufighter and in the introduction he says “To many eyes the aircraft deserved the accolade ‘If it looks right, it is right’. The Beaufighter, designed solely for combat, had a deadly beauty.” (JS, Introduction)

Note: If you do not have a sailing or flying background, then it might be confusing when I use the words port or starboard to refer to one side or the other of an aeroplane or ship. Here is the way to fix it in your mind. When you are at the controls, facing the way the vessel is going – port is left, which is red.

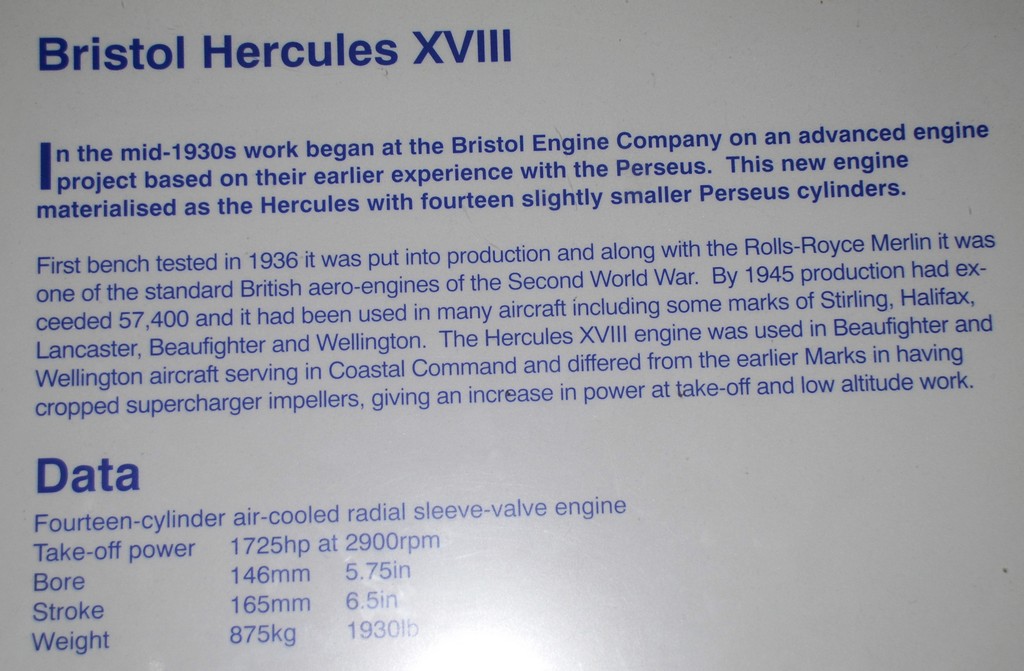

Dennis Gosling DFC, in his book Night Fighter Navigator said “219 Squadron was equipped with the new sensational Beaufighter … twice the size of a Blenheim with massive 1,600hp Hercules radial engines and it weighed over ten tons…. Its top speed enabled it to catch any German aircraft of the time, without diving…. fast, aggressive, powerful, awesome, brutal…” (DG p48/49).

And further described his delight at being posted to a Beaufighter squadron “… I was going to be entrusted with the latest, fastest, most heavily armed twin-seat, twin engined fighter, not only in the RAF, but in the world!” (DG p50)

The list of countries which owned and flew Beaufighters is quite impressive:

Australia (which built them as DAP Beaufighters)

America (it was said they had “joined the Stars and Bars”)

Dominican Republic

Israel

Portugal

Turkey

They flew in the skies of Britain for 20 years, until 1960. (JS, blurb) The engines were always made by Bristol and shipped to the assembly factories.

To give an idea as to how radical this design was, compare it to a modern airliner such as the Beech 1900D, a regional passenger plane in Nepal, New Zealand and Australia, as well as a freight and personnel carrier for the US military, manufactured in America. It was being built 40 years after the Beaufighter was withdrawn from service. The wingspan is identical at 17.63m (57ft 11in) but the fuselage is longer (17.63m). It is a twin turbo-prop with a maximum speed of 313mph and carries 19 passengers, to a ceiling of 25,000ft. The maximum take-off weight for a B1900D is 7,500kg, but for the Beaufighter it was 9,500kg, with a maximum speed of 330mph (450mph in a dive) to a ceiling of 30,000ft. The world of twin-engine propeller-driven aviation had gone backwards in 40 years.

Of all the aeroplanes ever built, the Beaufighter was produced in great numbers, 5500 of them, with engine production in excess of 57,000, and yet not one is flight-capable anywhere in the world today. I found that the main reason is because the Bristol Hercules engine that powered them are very difficult to find, and while other Bristol radial engines were used in, for instance, the post-war Bristol Freighter (a very common, and very large aeroplane, lumbering across the skies when I was young) they do not fit on the Beaufighter wing. This short blog on the progress towards that goal, points to a possible solution. Having opened the blog, scroll down a little to get to the Beaufighter article.

While we are discussing the engine, watch this video of a Bristol Hercules engine being test run. Maximum revs are only 2,900rpm, but look at the way it disperses the crowd behind the operator. It blows up a fierce storm. As you can see, the Hercules is a 14-cylinder radial engine, with an inner ring of seven cylinders matched with an equal number of outer cylinders, and once it warms up, it becomes surprisingly quiet. Here is a graphic of how it works. The early engines in development Beaufighters were the under-powered MkII (1100hp) and MkIII Hercules at 1400hp but good enough to give a flavour of how the plane would fly. (JS p9) The first production Beaufighters had to work with the MkIII engine, and the plane was delivered to 600 (City of London) Squadron at Tangmere on 12 August 1940. (JS p18) The Beaufighter was too late for the Battle of Britain but performed well during the London Blitz, operating as a night fighter, hunting bombers.

The Bristol Beaufighter was descended from the Bristol Blenheim, which was itself the fastest fighter-bomber in the world before 1940. Production started in 1937 (JS p8). A variant, heavier bomber, the Beaufort, was the Blenheim’s immediate descendant, but the Beaufort was never going to be a fighter given its relatively slow speed and high weight when fully laden. Production started in 1939 (JS p8). Bristol designers used the Beaufort frame, particularly the entire area behind the wings, and redesigned the wings and forward fuselage to allow a crew of two, the radar, and to accommodate the heavy 20mm Hispano cannon (all four of them) and their ammunition. (JS p9) The design also enabled the factories to re-use the jigs and tools already in use. This meant that Beaufighters could be produced quickly, and there was no need to develop new parts or processes in many areas of the continuing development of the aircraft.

The Beaufighter was second in speed only to the Mosquito, and then by just 30mph, and that in turn came about in the last two years of the war. But the Beaufighter was never retired from the fray. With its four cannons and six Browning .303″ machine guns, four on the starboard wing and two on the port wing, it was sometimes known as the “Ten-gun Terror”, and at other times “Whispering Death.” When the Australians started making the plane, they used .5″ Browning machine guns – to devastating effect. They scorned rifle-calibre weapons in aircraft.

The last flying Bristol Blenheim at home in Duxford.

We went to Duxford to see if we could find a Blenheim, and there was one sitting near the fence waiting for a chance to stretch its wings. In flight it was very quiet, especially in comparison with its fighter escorts.

Blenheim and fighter escort over Duxford 2016.

The type suffered badly during the Battle of France because even the Mk V (the latest version) had a Bristol Mercury engine with only 950hp. It was much too slow to be seen by German fighters in daytime and they were punished brutally. The hugely depleted Blenheim squadrons were withdrawn to Britain, to be used as night fighters and bombers. We chanced our luck to see if Duxford also had a Beaufighter, and a chap in grey overalls carrying some rather battered lengths of crumpled aluminium said there were bits of one in Hanger 2. And there was; it was labelled “a long term project” to turn an Australian Air Force Bristol Beaufighter back into a flying machine. A young Kiwi called Lawrence escorted us around the project.

Bristol Beaufighter at Duxford – the engine was a 14-cylinder radial motor.

Cannon bay and undercarriage.

Nacelles for the 20mm Hispano MkIII cannon. Two were tucked into the bay on each side.

A quick look inside the cockpit – there is a lot more instrumentation and control equipment to be fitted yet.

Elaine and I visited the Beaufighter at the National Museum of Flight in East Fortune, Scotland. The plane was in very basic condition but did give us lots of clues into the construction of the parts.

Above: Fuselage section. Below: end of wing cross-section.

Above: Probably the engine mounting. Below: Main part of the wing, the dihedral tail wing can be seen attached to the fuselage.

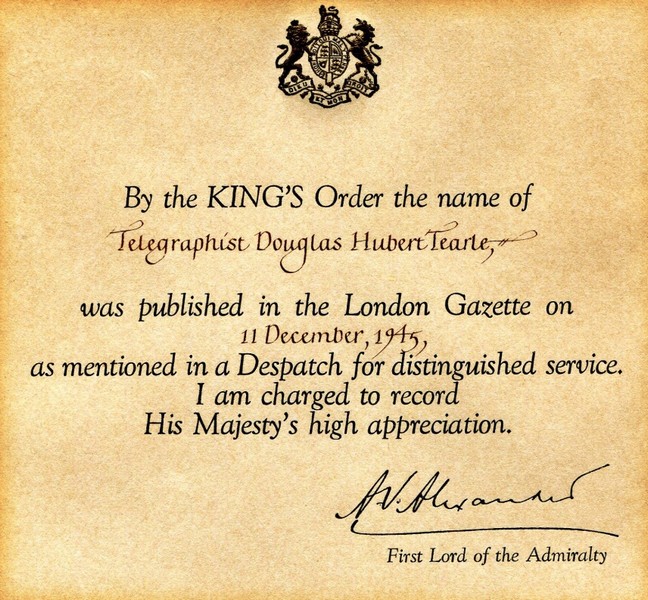

And then, on the last weekend before the exhibit was closed until 2018, we inspected the Beaufighter in the Historic Hangers of the RAF Museum, Hendon. The first photo of the exhibit heads this article.

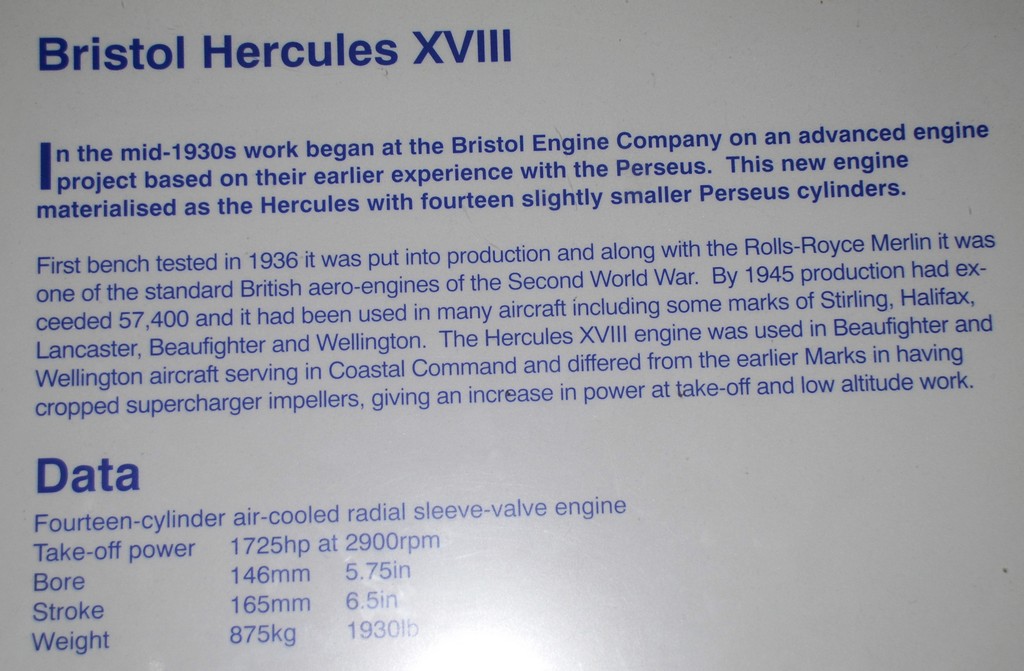

Bristol Hercules XVIII engine for the Beaufighter.

This is the black object under the port wing in the first photo of this article. You can see clearly in the photo above the two rings of cylinders. Below is the information board that accompanies the exhibit:

It might be worth noting that to the Coastal Command Beaufighter pilots, who were renowned for their bravery, low altitude (as in “low altitude work”, above) was called “dot feet.” Meaning sea level. The plane would be carrying a torpedo, and to stay under the radar and release a torpedo that would enter the water about 200m from the ship, the plane would fly literally at wave-top level. On dropping the torpedo, the Beau would open up with its cannons and machine guns on the ship – especially the bridge – targeting anti-aircraft guns and key decision-makers. Other Beaufighters in the attack would be firing rockets and possibly dropping two 113kg bombs in addition. They did not carry the torpedo with bombs, nor with rockets. The flight characteristics of each different type of weapon was quite different. The amount of venom the Beaufighter had was truly incredible.

There were two early marks of the Beaufighter – the Mk1F, denoting a fighter, and the Mk1C, which went to Coastal Command. The particular machine that is on display at Hendon is a TF.X, meaning it could carry a torpedo, or rockets and bombs – in addition to the cannons and six machine guns.

View from the tail

In the view above you can clearly see the 12 degrees of dihedral for the tail fins. This was an attempt – which had some effect – to prevent a savage yaw to starboard as the plane became airborne. Pilots were advised to keep the wheels on the ground until it reached in excess of 150mph, and to ensure that both engines had the same revs at take-off. (SC p15 & 17) You can also see the navigator/observer’s perspex bubble. You should note that it looks backwards.

Gosling says: “Although I had a marvelous view astern and to the sides, I had no view forwards, and obviously a navigator wants to see where he was going – not where he has just been! With practice I adapted to this back-to-front navigating, but it was never easy.” (GS p50)

The proboscis protruding above the engine is the air filter to the carburetors. The front wheels were fully retracted in flight, with fairings over them to reduce drag, however, the rear wheel when retracted still protruded a little and did not have a fairing.

Beaufighter TF.X at Hendon.

This view of the port side of the Beaufighter at Hendon tells us quite a lot. Firstly, you can see its size in comparison with the visitors nearby. One blade of the propeller is almost as long as an adult is tall. Secondly, you can see that the nose is tucked well inside the swing of the propellers, but it was still big enough to accommodate the bulky WW2 radar equipment. The little white drop-down object under the wing, close to the nearside edge of the photograph, is the pitot tube to tell the pilot how fast he is flying relative to the wind speed. You can also see the port wing landing light, and along from that on the leading edge of the wing are the holes of the blast tubes that contain the two machine guns. There are another four on the starboard wing. Along a little from the machine guns is the “bullet housing” for the oil cooler. Now, a little subtly, there are four small black marks on the underside of the wing on the same white streak as that occupied by the machine guns. These are mounting points for the rails that would have held the rockets, had she not been prepared for a torpedo mission. They are not in sight, and neither are the rockets in this view, but each rocket was covered by a blast shield to protect the wing when fired, and on many pictures of Beaufighters in flight, you can see the rockets protruding from the underside of the wings. Four on each side.

In one configuration it could carry rockets and bombs, or torpedoes and might operate with a crew of three, but in its usual configuration as a heavy fighter, it would have a crew of just two. The observer/gunner, so-called to disguise the highly secret radar the aeroplane was using, was actually the navigator and in our case he was Sgt FJ Tearle. The navigator would guide the pilot to a place about 300 yards behind and 100 yards below his target and after confirming the type of aircraft as a bandit, the pilot would give it just a 2-second blast of cannon and machine guns. The enemy plane would fall out of the sky. The cannons, machine guns and rockets were just as effective against E-Boats, U-boats and ships off the coast of Malta, as they were in Egypt destroying Rommel’s tanks and in the South Pacific harassing Japanese truck convoys and ground-straffing aerodromes and troop encampments. After the conversion of many Beaufighter squadrons to Mosquitoes, late in the war, the remaining Beaufighters were used by RAF Coastal Command to weaken and destroy enemy convoys in the North Sea.

Make no mistake, this is a thoroughbred fighter.

View over the starboard wing.

There are a few things worth noting in the photo above:

- you can just see the 3 degrees of dihedral in the wing, outside of the motor

- you can see the fairing that closes over the front wheels when they are retracted

- the rocket is held in place by one of its fins. The rails to which it and its three companions would have been tethered are not here, but they were heavily protected to avoid damage to the wing

- the four blast tubes for the machine guns can be seen on the leading edge of the wing; there was not enough room on the port wing between the oil cooler housing and the landing light for four machine guns

- the crocodile skin pattern of the exhaust pipe tail is to help prevent flare when the plane slows down in preparation for firing at a bandit. You can understand that at night, if your engines made a significant splash of colour, that would alert the pilot of the enemy plane and he would immediately take evasive action. In seconds he would be lost in the night.

- there is a bullet housing on the leading edge of this wing, too – for oil cooling. There are some photos here of details and interior views of this magnificent plane.

The Beaufighter Mark II

We can spend a moment on the Mk II. There was some worry at Whitehall that Bristol might not be able to maintain the production of their Hercules engines, so Rolls Royce was asked to supply Merlin engines to the Beaufighter production line, and Bristol agreed to try to make the mark work. The plane looks nose-heavy because the engines are fitted to the wing from their rear, and project well forward of the nose. In flight, the engines, Merlin Mk XX at 1280hp, were not powerful enough for the size, weight and required airspeed (they could fly only 301mph) of the planes to which they were fitted. The project had some Mk II production planes delivered to 600 Squadron in April 1941, but they were replaced by Beaufighter Mk VI with Hercules engines in May 1942. This was about the time when Mk II production finished. The Navy liked them because they had Merlin engines so Naval engineers did not have to get used to a new technology, but in the end few of the Merlin Beaufighters saw active service, and it was Merlin engines that suffered production shortages. All the Merlin Beaus – Mk II, Mk III, Mk IV and Mk V – none of which looked like a Beaufighter, and were difficult to fly, with an even more alarming starboard yaw on take-off – ceased production. The last word goes to an RAF accident inspector: “Every effort should be made to re-equip Beaufighter squadrons with Mk V1s. Hercules engines are more reliable.” (JS pp24-35)

My brother Graeme and I went to the Shuttleworth Collection at the Old Warden aerodrome, and we found this:

Hispano cannon and Browning machine gun, Shuttleworth Collection.

The round object, like an electric motor on top of the cannon, is the belt feed mechanism that loaded shells into the breach.

Hispano 20mm cannon muzzle.

The photo above is just to keep you awake at night… It is a mighty weapon.

Comparative bullet and shell sizes

This picture shows the different types of shell that could be loaded into the Hispano cannon belt – all the same type, or a mixture – depending on the target the plane was hunting. Two cannon were fitted into each of the bays I pointed out in the Duxford Beau, above, and the area around the bays had to be greatly reinforced, with the barrels contained in heavy-duty blast tubes. The pilot alone controlled the firing of the plane’s armament, and during night patrols relied wholly on the navigator putting him in the right place and at the right speed to launch an attack. You can see how comparatively small the .303″ Browning machine gun is. It was developed for ground-based battlefield conditions against approaching soldiers; it seems a very small bullet to be using to attempt to bring down an aeroplane.

There is a moot point we could discuss at this moment; how does a ten-ton monster get such a turn of speed? My flight instructor, Malcolm Campbell of the Eagle Flying Academy, while we sat in a little Piper Cherokee and waited for take-off clearance from the tower, summed it up like this. “What do you think keeps this plane up in the air?” he asked me.

“The wings,” I said. “Air flows over them and because the wind over the top of the wing has to go further than the wind under the wing, that causes lift, and we can fly.”

“Not bad,” he said, nodding at my 5th-form science. “But consider the rocket, it has no wings. What makes it fly is the rocket engine. There are unbelievable amounts of energy and power released when the motor is turned on. Without power, the rocket is a large metal cylinder, going nowhere. So what keeps us up in the air?”

His foot tapped on the firewall that curled up from the floor to the windscreen in front of us. “This motor; it generates power, and up we go. If it had enough power, a brick could fly.”

“Foxtrot Papa, you are cleared for takeoff,” said the voice in my headphones.

“Push the throttle all the way forward and hold the plane on the ground until you have reached 80mph,” said Malcolm, “then gently, very gently, ease the control stick towards you and the plane will rise. Let the motor do all the work. Once the plane is rising, hold the nose at that attitude and wait while the airspeed increases until it is over 110mph, then you can let it rise as it wants to, until we get to 5000ft.”

He looked out the window as the aerodrome retreated below us and the Rukuhia countryside unfolded its rural splendour in a glorious summer panorama of green paddocks dotted with houses and milking sheds, and ribbons of black roads winding through undulating hills framing the sparkling blue waters of the mighty Waikato River. “Without the power of this motor, you’d still be on the ground.”

Those nicknames

“Ten-gun Terror”

I can live with this name because it was so obviously dreamed up by a focus group in the War Office and thereafter used extensively in propaganda. It has such a nice alliteration, it rolls off the tongue so sweetly, it makes the aeroplane sound really tough, and it is a simple description of the Beaufighter’s most important asset. WW2 movie-goers would have thrilled at the name when they watched newsreels of this plane swooping down with all guns blazing.

“Whispering Death”

I wondered about the origin of this name when I first heard it in one of the newsreels. “The Japanese call it the Whispering Death!” bellows the commentator, but it sounds like propaganda, and it seems unlikely that the Japanese would have thought up the phrase, and then handed it to the War Office to use against them.

Dennis Gosling mentions it:

“… the Beau was almost noiseless when making a ground attack and it later became known as the “Whispering Death” for by the time the sound reached you the plane had already gone.” (DS, p64)

However, Jerry Scutts has the definitive version:

“It was actually British pilots who dreamed up the enduring name for the Beaufighter, after a Mess party where someone with fake newspaper headlines in mind christened it Whispering Death.” He goes on to describe the attack of a single Beaufighter on a Japanese parade ground in Burma celebrating the emperor’s birthday on 29 April 1943. The Japanese had not heard the low approach of the Beaufighter, which, as it overflew the parade killed a number of troops, frightened the horses and split the flagpole, symbolically bringing down the Rising Sun. “The most dramatic and enduring nickname has been associated with the Beaufighter ever since.” (JS, p136)

Malta

There is a lot to be said about Malta and the Siege of Malta, and I intend to do so in another post. Suffice it to say that all these stories came to notice because of Sgt FJ Tearle. Here he is with 89 Squadron in the burning sands of Abu Sueir, and he looks at the noticeboard in the Sergeants Mess. Dennis Gosling has the list:

“89 Squadron crews posted to 1435 Flight Detachment Malta

Flight Lt Hayton and PO Josling

PO Daniel and Sgt Gosling

PO Oakes and Sgt Walsh

Sgt Miller and Sgt Tearle.

…. no matter that we were on our way to the most bombed place on Earth, this was the adventure we had craved.” They flew four Beaufighter aircraft to Malta and landed at Takali, “a grass airstrip without any night flying facilities.” (DG, pp74-75)

He calls them “Eight little Night Fighter Boys of Malta Night Fighter Unit No. 1435.” (DG p77).

The conditions on Malta were very serious. They were in the middle of a siege with the Germans and the Italians bombing Malta constantly, with little food because the convoys seldom made it to Malta, and what they had becoming scarcer with every passing day. These four Beaufighters were the night defenders. The Beau crews cycled from Valletta to Takali where their planes were, and they were sent up in pairs to patrol the night sky. If the control tower, using very early and primitive radar (called AI for “Aircraft Interception”) sees “trade” as it was called, they would “vector” (assist) the nearest Beau onto the object. Once the navigator (Tearle, in this instance) had seen the unknown aircraft, he would inch the Beaufighter below the intruder so they could see it against the night sky and he and the pilot would check for signs that it was friendly, or a “bandit”. Friendly planes should have a light of the correct colour for any particular day, and they would also check the outline to see if they could recognise it as a known aircraft type. If it was definitely one of the enemy, the Beaufighter was allowed to attack. “Dusty” Miller and Sgt Tearle notched up 1435 Flight’s first kill on 8 March 1942, by downing a Ju 88 and damaging an He 111, which was not destroyed because the gun jammed. (DG, p78)

There was an ongoing problem with the gun jamming (more accurately, the cannon) and reasons for it doing so are many. It was a serious matter, because neither the pilot nor the navigator could re-arm the gun in flight. The Hispano was not, in its own right, an unreliable gun, since it was widely used in many military situations, but Gosling would test-fire the cannon of 1435’s Beaus each time there was a new shipment, because he thought there were good batches and poor batches. As a result, it would appear, gun jammings were reduced in number.

Once the Siege of Malta was over, other squadrons could come and go more or less as they pleased, and in due course, Malta was used as one of the jumping-off places for the invasion of Italy. Here is a Beaufighter of 272 Sqn taxiing near Mdina.

Wrapping it all up:

No-one can say the Beaufighter is pretty; it is too short from nose to tail, it looks ungainly at rest, the cockpit sticks out of the body incongruously – and the motors are huge, like bulging eyeballs. But beauty is more than just pretty – there is an organic synthesis of form and function that Jerry Scutts referred to in my introduction. Everything about this plane speaks of intent. In action, they were hazardous at take-off, but the pilots who flew them say that everything after that was delicious. They also floated well after landing in water, and often both crew members would survive a ditching. Furthermore, it was well known in RAF Beaufighter squadrons that the best way to land a wounded Beau was with the undercarriage retracted. Broken propellers and some scuffing of the underside of the plane would be fixed, and the aeroplane could be ready to fly again in two days. (JS p105)

Jerry Scutts says: “Although the Beaufighter was capable of destroying enemy fighters if its pilot was able to bring its formidable armament to bear, but in a disadvantaged position to an Fw 90 or a Bf 109, it would be hard-put to outmanoeuvre a well-flown plane.” (JS p20) The enemy planes were not faster, but because they were lighter, they could turn inside the Beau’s turning circle, and start firing at it before the pilot could get a bead on the little fighter.

Which is why the Beaufighter was a night fighter, a tank-buster, a ground-strafer and a ship-destroyer. What the Beaufighters had was a built-in grace in the air, and a very fast turn of speed; they could reach 450mph in a dive, but the pilot had to have plenty of room between the plane and the ground to pull up so that all the weight of the plane could be re-directed. They were quiet in flight, they could stay in the air for over five hours and their armament made them an enemy from which any man would be best advised to stay well clear. When you look through some of the videos I have assembled for you below, you will see just how fast, and how gracefully the Beaufighter flew; and you will also see how deadly and destructive was its firepower.

It was a warhorse of quiet power and deadly beauty, and it has a history in combat of which all of us can be thoroughly proud.

Footnote:

Graeme asked the Airforce Museum of New Zealand if they knew anything of Beaufighters in New Zealand. Research Officer Tony Moody replied:

“No. 489 (NZ) Squadron was formed in the UK and only ever served there. We are not aware of any Beaufighters being on the RNZAF register in New Zealand at any time and the ones employed by No. 489 Squadron were definitely RAF and stayed over there. As you say, it is possible Aussie “Beaus” could have staged through New Zealand or Norfolk Island. We did get Mosquitos here in New Zealand post war though.”

This is why New Zealand is not listed in the section on Beaufighter owners.

There is a chance that a Beaufighter (or rather the forward section of one) has found its way to the Warbirds Museum on Ardmore aerodrome in Auckland. Graeme is investigating.

References:

Gosling, Dennis; Night Fighter Navigator: Beaufighters and Mosquitos in World War II. Pen & Sword Aviation, 2010. ISBN: 978 184884 1888

Scutts, Jerry: Bristol Beaufighter. The Crowood Press, 2004, ISBN: 1 86126 666 9

Online Resources:

1435 Flight

http://www.raf.mod.uk/history/1435squadron.cfm 1435 Flight/Squadron history

https://maltagc70.wordpress.com/2012/03/01/1-march-1942-9-hours-of-night-bombing-20-killed-in-floriana/ Malta WW2 day by day diary. Starts 1 March 1942, can see progress of 1435 flight.

http://home.btconnect.com/myrcomm/beaufighters/beau/index.html Beaufighter Squadrons

http://www.worldwarphotos.info/gallery/uk/raf/beaufighter/bristol-beaufighter-mk-vif-f-freddie-of-no-272-squadron-malta/ Beaufighter taxiing in Malta

http://www.worldwarphotos.info/gallery/uk/raf/beaufighter/ Collection of wartime Beaufighters

Beaufighters at war – youtube videos

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsUdbzQCm_Y (Ten-gun terror – Beaus used against North Sea shipping, and Rommel’s retreating army.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hL4_z3kWa3s (Sinking minelayer in Fiume)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psUvAUw37D8 (Whispering Death – the forgotten warhorse)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbzoCKKCQvE (Simulation flight to Sicily)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQqwQH7Dnqg (Diving on WWII Beaufighters in Norway – Documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tTA7-83GFII (Beaufighters straffing retreating desert forces)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KR2OTc6_3-g (Beaufighters attacking shipping)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4XPIjsW3Rc (Beaufighters in action)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X42zerXRfwc (Beaufighters of 254 Sqn John Care pilot)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nuTarFsQLQc (Beaufighters of RAAF 455 Sqn)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbzoCKKCQvE (Beaufighter at Hendon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=buUivVLUyQo (South African Beaufighter pilot)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EygPHew2q58 (Aus and US Beaufighter pilots)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVvj659sBAA (Diving on a Beaufighter wreck off the coast of Malta)

Beaufighter engine restorations

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTl7ZsM3Fvo Last Beaufighter engine run 1983

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIYrPGRNRHo Beaufighter engine restored and run

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEbDlNeMtLM Bristol Hercules demo run

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0q9l8xejrE Bristol Hercules sleeve valve radial engine

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6Zw1_NiSWg First start Bristol Hercules

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5b3uN2jJMQ Rolls Royce Merlin and Bristol Hercules engines at Farnborough

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-BzHEBJ3rw Bristol Hercules engine running – Bomber Command Museum of Canada

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LJ-FSJ7El2Q Bristol Hercules engine run Duxford flying legends 2015

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVxHOmQfh4Y Bristol Hercules engine in a Bristol Freighter Omaka Aerodrome Blenheim NZ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzXeFql-1VU Bristol Hercules engine startup

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_vrvep_YOio Bristol Hercules sleeve valve radial animation

Beaufighter restorations

http://www.warbirdsonline.com.au/2015/08/31/bristol-beaufighter-news/ Warbirds online Albion Park NSW restoring a Beaufighter.

http://www.warbirdsonline.com.au/2014/07/02/dap-beaufighter-engine-restoration/ Beaufighter engine restoration.

http://farm3.staticflickr.com/2489/5839768225_3f13f7d765.jpg Sent down-under; this looks like a static trainer.

http://forum.keypublishing.com/attachment.php?attachmentid=221015&d=1379608166 The same Beaufighter as above; I think this is the one now at Warbirds Ardmore in Auckland.

https://shortfinals.wordpress.com/2011/01/27/big-and-burly-a-plane-with-a-problem-its-a-bristol-beaufighter/ Comments on the Beaufighter restoration at Duxford.

http://www.warbirdsnews.com/warbird-restorations/warbird-restorations-downunder-rob-greinerts-workshop.html The HARS workshop in Australia. Scroll down a bit to see a most interesting comment on the future of the Beaufighter.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No._489_Squadron_RNZAF No 489 (NZ) squadron had Beaufighters from Nov 1943 to Aug 1945, when the unit converted to Mosquitos.

http://rnzaf.proboards.com/thread/19894/bristol-beaufighter-detail – a Beaufighter in the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune, Scotland in 2013. Since moved to Hendon.

Beaufighter stories

https://maltagc70.wordpress.com/2012/03/08/8-march-1942-luqa-bombed-round-the-clock-325-high-explosives/ Sgt Miller and Sgt Tearle on mission in Beaufighter from Luqa

http://www.rafcommands.com/forum/showthread.php?4659-F-Lt-Reginald-Arthur-Miller-(123201)-26th-April-1945/page2 Death of Dusty Miller

http://www.bbm.org.uk/airmen/Tearle.htm Photo and headstone of FJ Tearle

http://www.epibreren.com/ww2/raf/600_squadron.html 600 Squadron in BoB

http://www.ipmsstockholm.se/home/bristol-beaufighter/ Development of the Beaufighter

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_beaufighter_history.html History of the Beaufighter

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:No._489_(NZ)_Squadron_RAF#/media/File:Royal_Air_Force_Coastal_Command,_1939-1945.._MH6449.jpg Royal Air Force Coastal Command, 1939-1945.. Beaufighter TF Mark X, NT946, of No. 489 Squadron RNZAF, setting out from Langham, Norfolk, on an anti-shipping strike, carrying an 18-inch torpedo fitted with a Monoplane Air Tail. By Royal Air Force official photographer – http://media.iwm.org.uk/iwm/mediaLib//50/media-50921/large.jpgCatalogue number MH 6449Database number 205207954Transferred by Fæ, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24397065

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:No._489_(NZ)_Squadron_RAF#/media/File:Royal_Air_Force_1939-1945-_Coastal_Command_C4469.jpg Beaufighters attack shipping. Royal Air Force 1939-1945- Coastal Command A Beaufighter of the Langham Strike Wing in action on 15 July 1944, when 34 Beaufighters from Nos 455 and 489 Squadrons, operating with No 144 Squadron from Strubby, surprised a convoy off the southern coast of Norway. HQ Coastal Command, Royal Air Force official photographer – http://media.iwm.org.uk/iwm/mediaLib//60/media-60398/large.jpg This is photograph C 4469 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.