By Ewart Tearle

Mar 2015

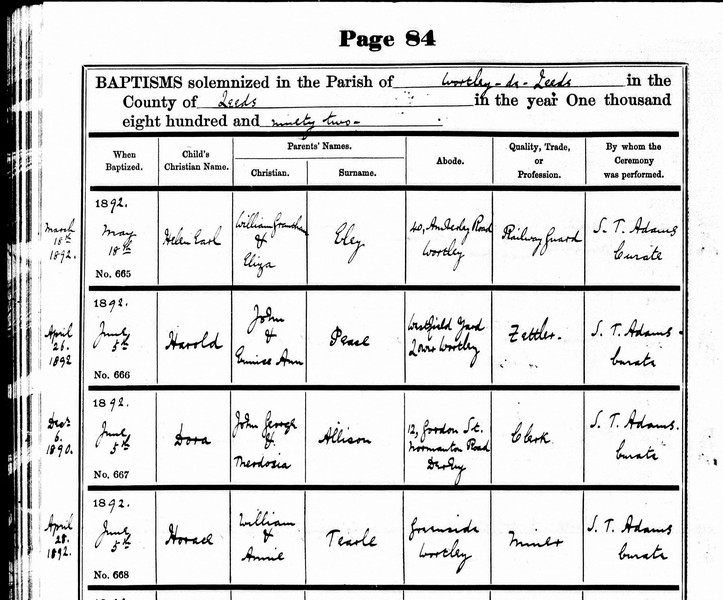

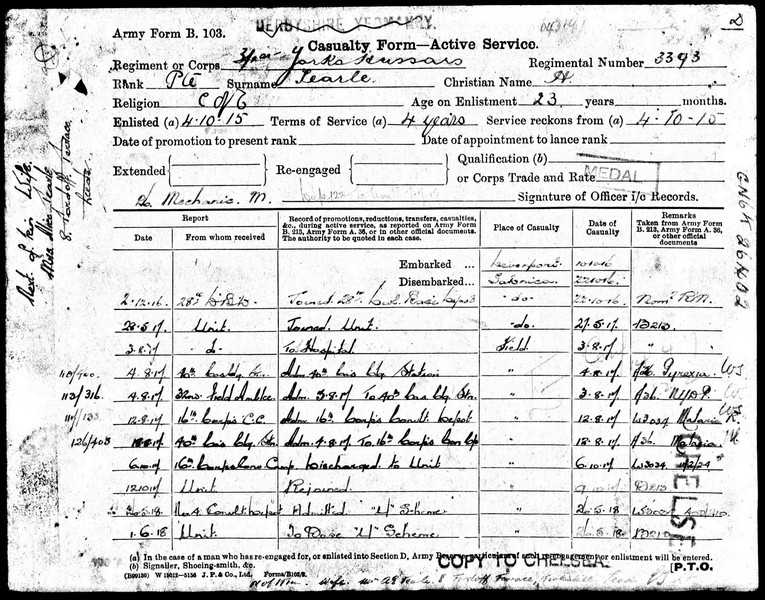

For a very long time, only two sets of records existed for Montague Tearle; his marriage in the third quarter of 1915 to Lilian A Boulter in Derby, and his death in 1939, aged 63, somewhere in Hackney, London. There was no record of a birth certificate. The second set was from Chelsea Hospital, and consisted of his military and health records.

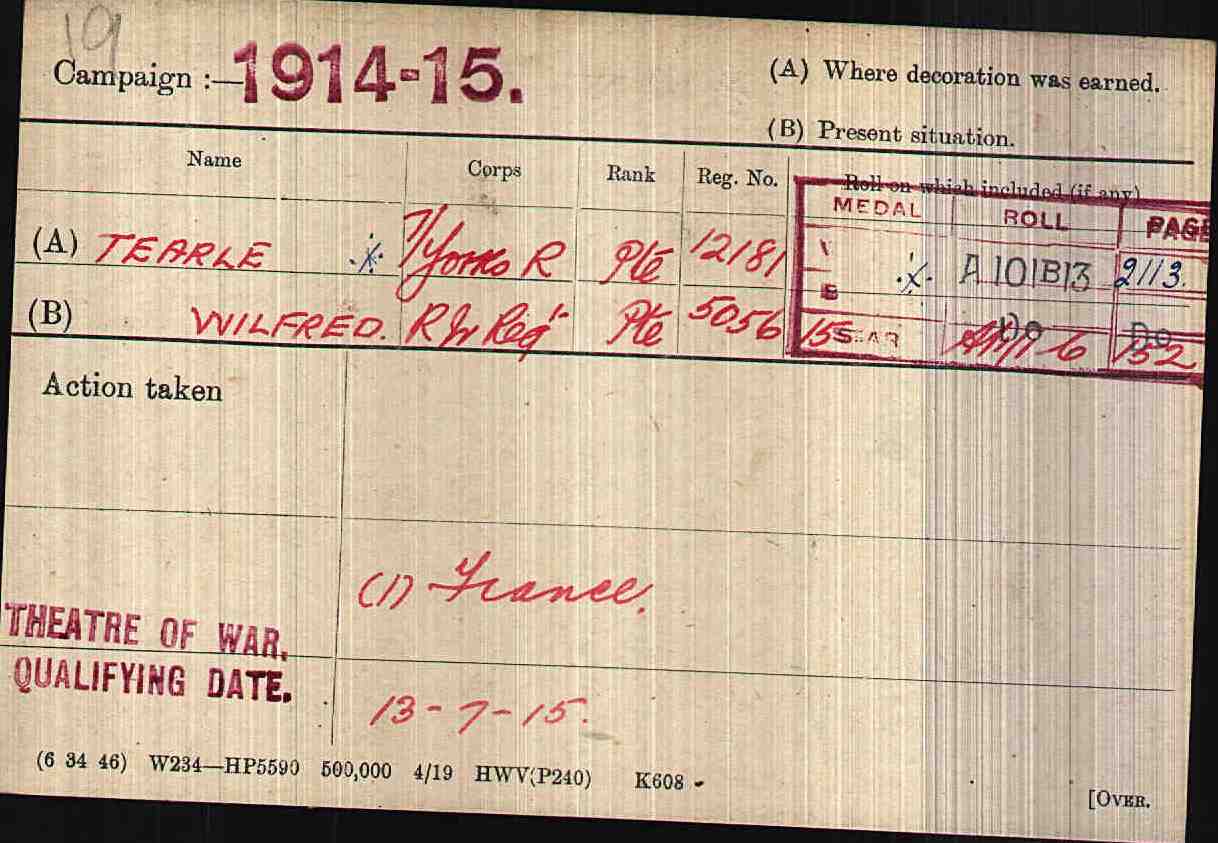

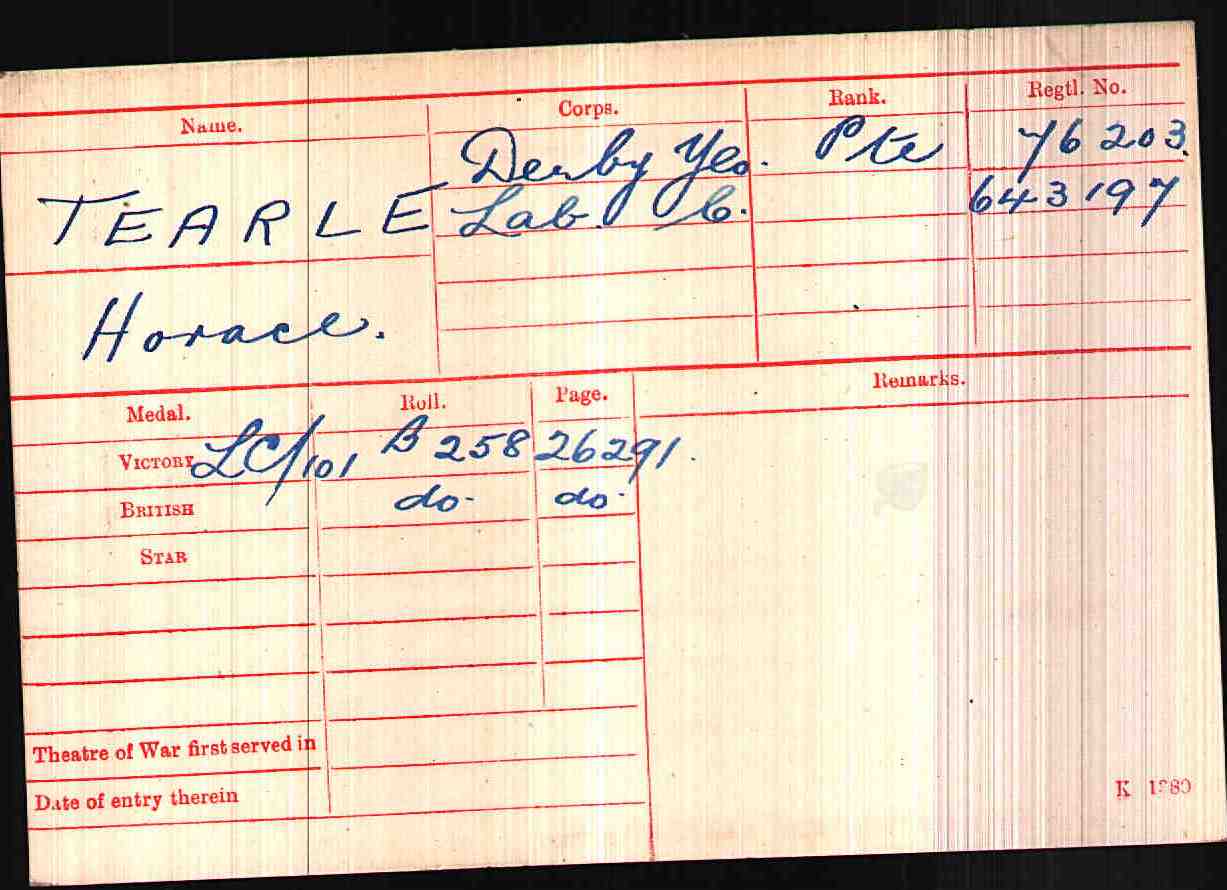

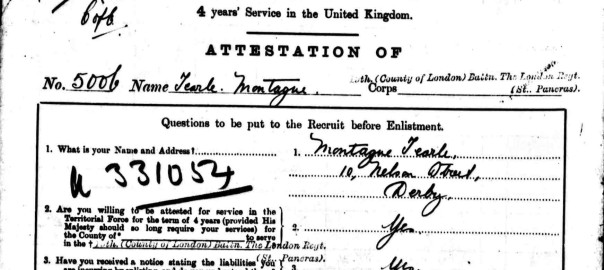

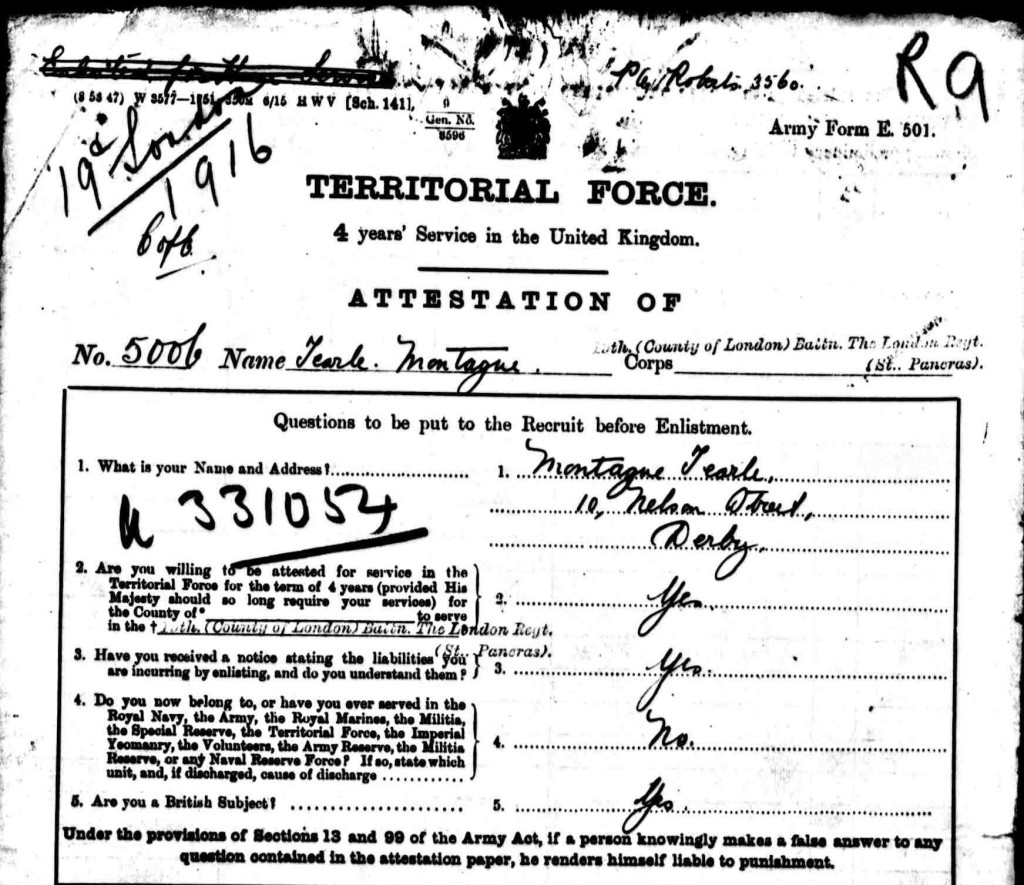

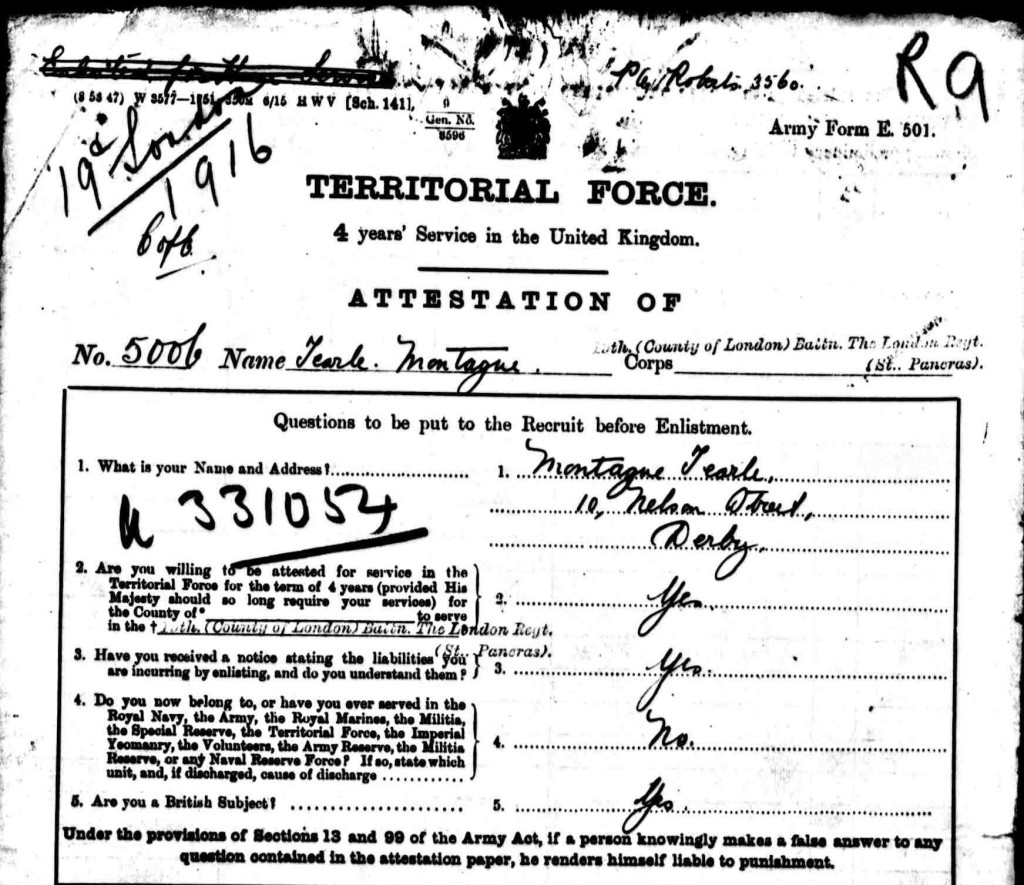

He enlisted for the army on 10 Oct 1915. The recruiting officer wrote his name as Montague Tearle, but his signature was Monty Tearle. He was given the military number 5006 and on attestation day he was put in the 19th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment, headquartered in Camden Town. Monty’s home address was 10 Nelson Street, Derby.

Montague Tearle attestation for Territorial Force

The second page of Montague’s army record was his Medical Inspection Report, which was conducted on 23 Oct 1915. He was 38yrs 6mth old, 5ft 10.5in tall with a 37in girth he could expand and contract by 2in. His vision in both eyes was 6/6, and his physical development was good. He was pronounced fit for service, subject to some dental treatment.

The third page recorded his acceptance of the service obligation – to serve anywhere he was posted and in whatever corps he may find himself at any time, subject to a condition placed on the army itself not to post him on any transfer where he would suffer a loss in pay. He duly signed that one.

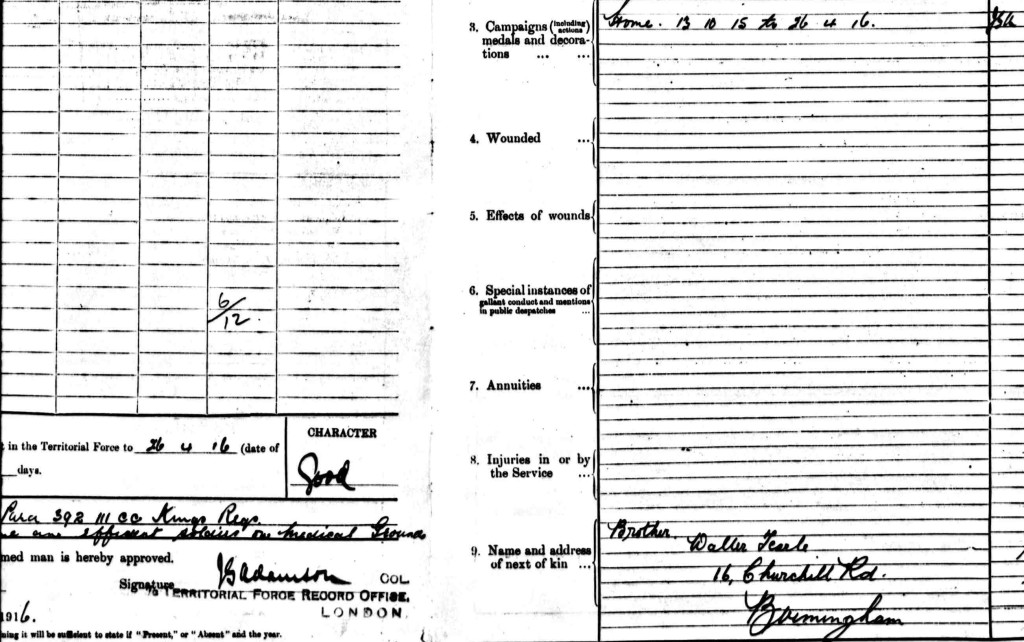

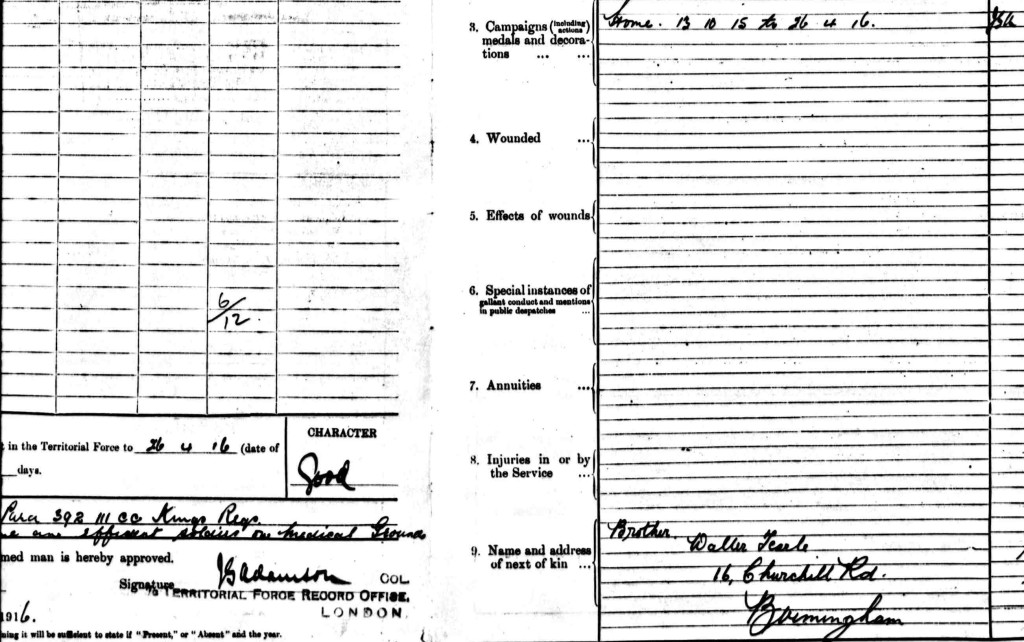

The fourth and fifth pages are a double page of the same book – his service. It only has a few lines. He was “embodied” in the army as a Private (their capitals) from 13 Oct 1915 to 26 Apr 1916, a total of 197 days. A sad note on the left-hand page says, “…. Kings Regs; Not likely to become an efficient soldier on Medical Grounds” again, their capitals. Dated 24 April 1916. His record was “Home” meaning anywhere in Britan, including Ireland, 13/10/15 to 24/4/16. So he had no claim to any service medals, and no claim to pension. His next of kin was “Brother – Walter Tearle, 16 Churchill Rd, Birmingham.”

Montague leaves the army

However, Montague did claim for pension: The next document from Chelsea Hospital was dated 29 June 1916 with a determination made on 15 July 1916 – Montague Tearle 5006, with regard to claim for pension: Rejected. What was he thinking of? All claims to pension were based on the number of days a soldier was in the army, so long as he had a posting abroad. Montague would have known that – he was trying it on.

He had another go in 1929 – the last two documents are from Chelsea Hospital and they record a request for information from the Kent County Police on 1 Sep 1929 to the London Infantry Record Office stating that Montague Tearle was under the care of the doctor in charge, British Legion Village, Preston Hall, Aylesford. “Some doubt exists as to the genuineness of this case, and I shall be glad if you would furnish me the particulars of … his service, and his description.” On 6 Sep 1929, the Chelsea Hospital received the form requesting the discharge documents “for the purpose of being annexed to his later Discharge to pension.” It would appear he was again claiming his pension, hoping that time had dulled the bureaucrats, or he was trying to stay in a soldier’s care home to which he only had access if he was on pension.

At first appearance, Montague’s request to join the army seems to be for the best of motives – he was 38yrs old and he was going to fight for his country. But in the light of his later activities this impulse looks a little less than the self-sacrifice he intended it to appear. He gets free dental treatment on the army and for 197 days he was quartered for free, as well actually being paid.

He does not appear (and neither does Walter Tearle) in any census from 1880 to 1911. There is no birth record for a Montague Tearle and all the Walter Tearles (nine of them) are accounted for in other families.

Ten years after Montague and his very reticent (not to mention almost invisible) brother came to light, Barbara Tearle of Oxford unearthed some newspaper clippings that recorded some of Montague’s activities. They are not pretty.

Bath Chronicle Thu 30 May 1907

Cyril Dudley Vincent, a music hall artist, was in the Bath City Police Court for having produced documents to back up a claim of having money, and asking for a loan on the strength of the documents. He raised the loan, but couldn’t pay the lender, hence he landed in court on charges of false pretences. The name on the letter was Montague Tearle, who said Cyril was a property-owning gentleman. It turns out that Cyril in the dock, and Montague on the documents, were the same man.

Montague never has any money, but he lives the life of a gentleman of quality. He uses the conventions of the gentleman to con the unwary and the trusting. We can see, above, that Montague joined the army in 1915; in the light of just this one conviction, it would not appear that the army was too concerned about the moral or criminal behaviour of its recruits for the Great War.

Morpeth Herald and Reporter Fri 26 Jan 1917

The Theatre Royal in Blyth, Northumberland, was opened in 1900. It was a well-known and well-respected local institution by 1917, when Montague Tearle became its manager. This report in the Morpeth Herald, which often had articles on Blyth, centres on Mr Tearle’s capacity as a very popular man who raised the considerable sum of £10 3s 6d for a local military charity. Mr Tearle, it was noted, was the son of a most famous Shakespearian actor, Edmund Tearle, who had played to Blyth audiences in this very theatre. Mr Tearle’s role as an ex-soldier in the Pals Battalion of the London Regiment was noted by the gold braid badge of honour on his sleeve and the stories of his exploits since 1914 in the Great War, where he had fought in the Battle of Loos in France, been injured and gassed and finally passed out of the army due to ill health. Sadly he was leaving the Blyth Theatre for the Raynor’s Repertoire Company as General Manager. He was later presented with a handsome silver Treasury note-case by a group of military officers.

It is quite likely that none of this is true; Montague was probably not the manager of the Blyth Theatre Royal, and the paper has not checked his assertion. He has raised £10 3s 6d and equally probably kept it all. He is not the son of Edmund Tearle of Leighton Buzzard, who was indeed a famous actor/manager but he is very keen to trade on Edmund’s name. Within nine months of leaving the army, he has literally embroidered his jacket cuff to embellish his story as a Great War veteran. As we know, he was never in France, never gassed, but he was invalided out of the army – one tiny fact to ground all the war stories he is happy to relate. He is leaving Blyth in a hurry, and stole a silver Treasury note-case on his way out. If we take another look at the 1907 court case, there are some similarities, which show a pattern in his behaviour – he is always in theatre, sometimes a manager, an actor, or an agent. This is why he has adopted the name Tearle: his contemporaries are George “Osmund” Tearle the actor/manager, Osmund Tearle (son of George) the actor manager, Edmund Tearle the actor/manager and possibly by now some whispering of the genius of Godfrey Tearle (born 1884) also making his way towards theatrical fame. The name is beginning to have some credibility.

Bucks Herald 15 Oct 1921

Montague Tearle, aged 46, of Leicester, a theatrical agent, was in the dock at the Bucks Assizes, charged with the theft of 8 Treasury notes valued at £5 10s, a 10s Treasury note and 7s 6d from various people overnighting in the Railway Hotel, Linslade. He was found guilty because everyone who had been stolen from had wax droplets in their room, and Montague was the only person who had a candle. The judge noted that between 1892 and 1905, Montague had been convicted in various courts no less than 15 times. Since 1905, he had been imprisoned for two terms of five years and there were other terms of imprisonment with hard labour. The prisoner wanted another chance, saying that his offending was due to the difficulty of finding work, and that he was very sick, spitting blood, and wanting to get back to Leicester. The prison governor said his sickness was due to refusing to eat while he was in prison since 31 August, awaiting trial. The judge sentenced Montague to twelve months in prison. This story was gleefully retold by The Northampton Mercury on Friday 21 October under the headline TRACED BY CANDLE GREASE.

Montague has even gone to Leighton Buzzard, the home of Edmund Tearle. What did they think there of a man claiming to be Edmund Tearle’s son, but speaks with a Yorkshire accent? Has he borrowed someone else’s accent as well while he is in Bedfordshire? The story above would be amusing if it wasn’t at the same time quite tragic. Montague’s life is a mess; look at the sorry list of convictions the judge above has noted, and the two terms of five years in gaol. He is 46 years old, and he has spent no less than 10yrs in prison. If he is spitting blood, does he also have TB?

The Herald 29 Mar 1924

The Leicester newspaper reported that Montague Tearle had appeared on bail in the Tamworth Borough Petty Sessions charged with arrears on an affiliation order. The arrears went as far back as 1918 and amounted to £60. Montague argued he had been very sick in hospital and in a sanatorium. He had found it difficult securing work due to his illness, but he thought he had a promise of work, and as soon as the doctor would allow him back to work, he would be able to pay the arrears at the rate of 10s per week. The mayor said the magistrates would give Montague the chance to repay at the stated amount.

Leicester is where Montague has housed his wife – his very long-suffering wife, Lillian – and Montague is pointing to ill health as a reason for his misfortune. It is relatively true – surely you can’t blag your way out of a war-time army by feigning sickness. And it may also be true that sickness has largely prevented him from keeping a job, but perhaps also there is a moral sickness, and he just cannot help himself from seeking the rush of pleasure he must have felt when he successfully talked someone out of their money.

Lincolnshire Echo Fri 20 Nov 1925:

Charged in the Ilkeston Police Court on false pretences. He had told the court he was a theatrical agent and was in Ilkeston on the chance of getting a job at the local theatre. He was remanded for a week.

There is no later edition to say what happened next – and whether he was convicted – but there are worrying similarities to other appearances in court: false pretences, theatrical agent, looking for work …

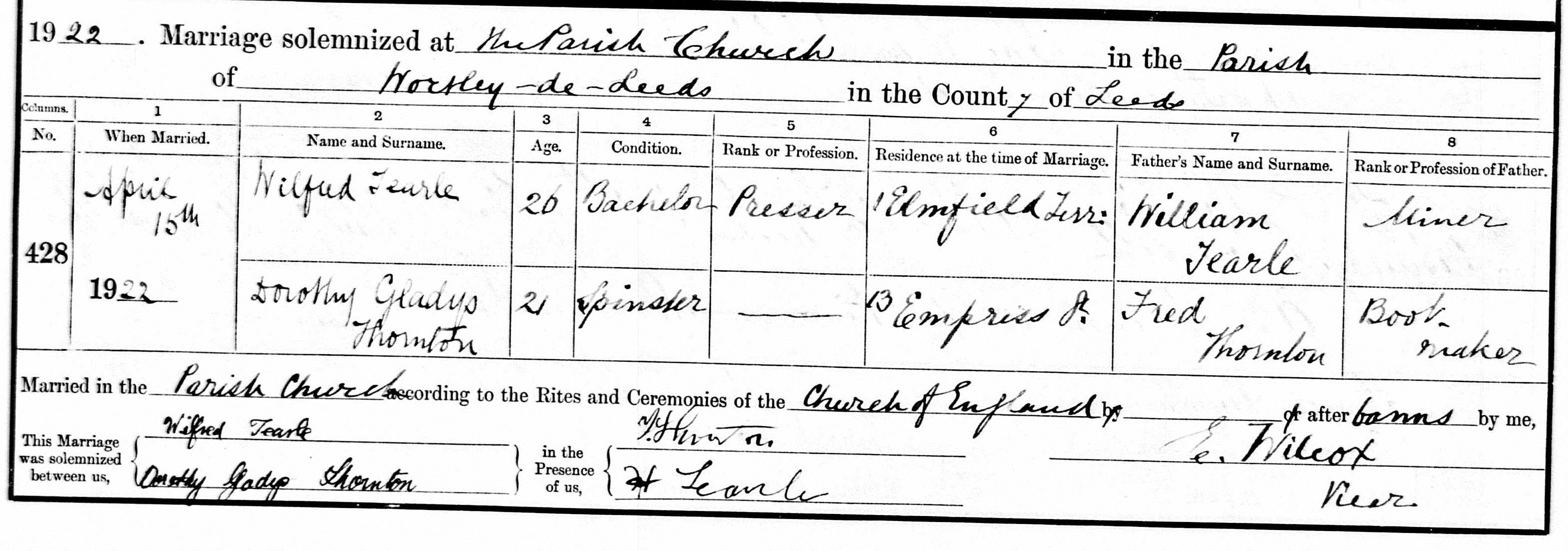

Pat Field of the Yahoo Tearle Group, noticed that Lillian A Boulter was listed twice in the marriages index, once with Montague Tearle and again with a William Woollen. Also, if William Woollen’s marriage listing in the index was examined closely, William Woollen also married a Lillian A Boulter on the same day, in the same place – Derby. She also noticed that Montague Tearle and William Woollen had the same date of death, and the same address; furthermore, they were on the same page of the index:

Montague’s marriage was in the Oct-Nov-Dec quarter of 1915 – around the same time he joined the army, and of course his address is Derby; that is where he was so recently married. Is it significant? Did Lillian have some savings? Or did he want the respectability of being a married man?

The story of the censuses

In order to uncover the story of a person between 1841 and 1911, the censuses are a reliable and necessary resource. In this case, they provided conclusive evidence of Montague’s identity.

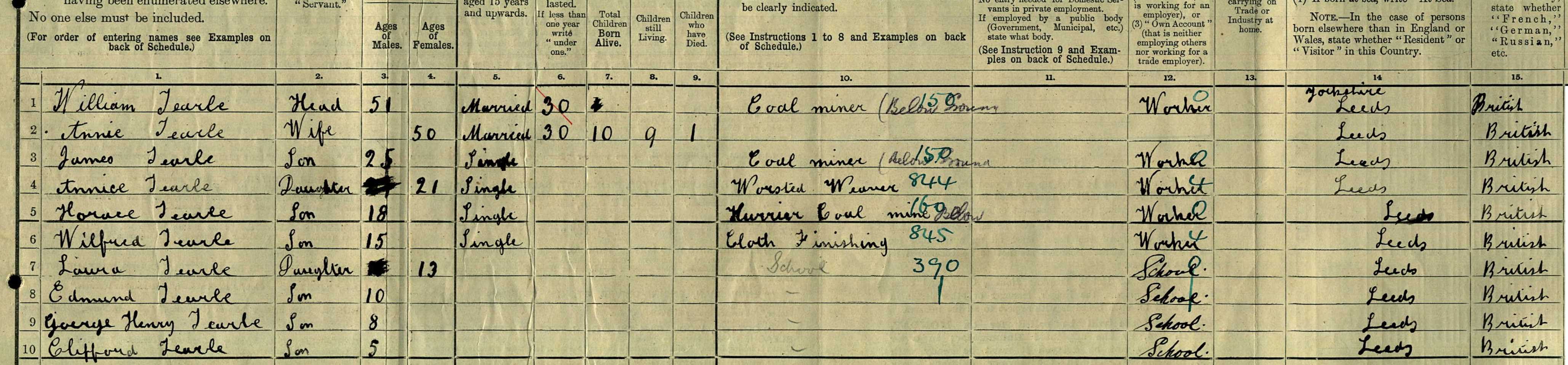

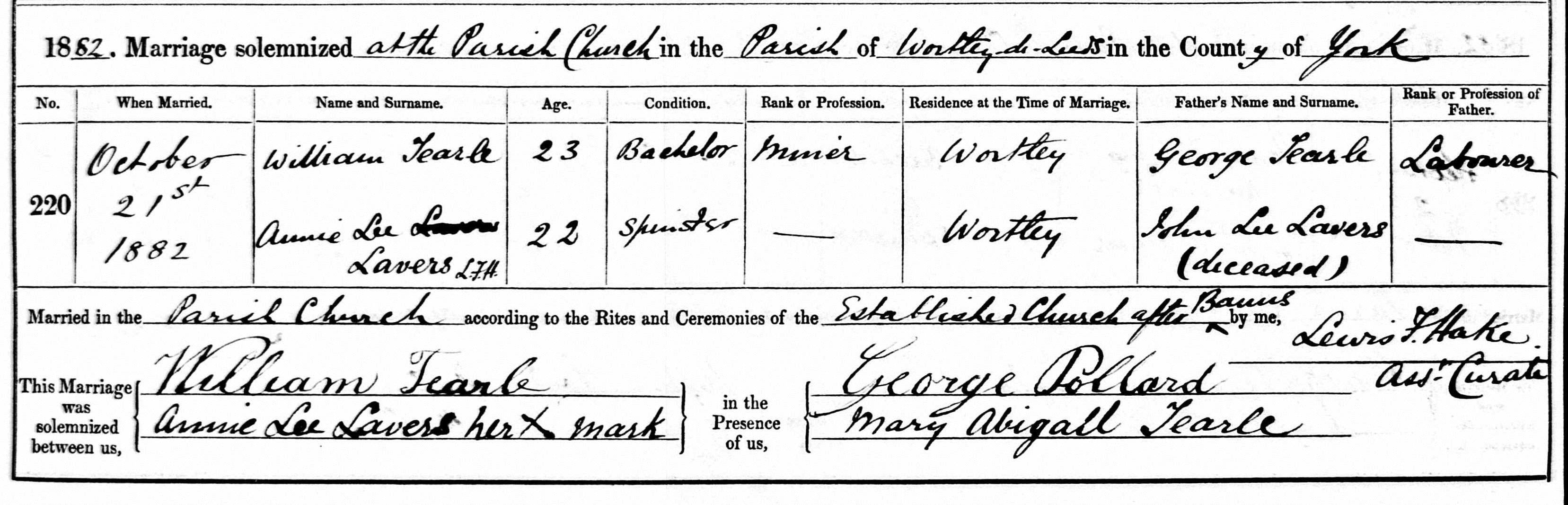

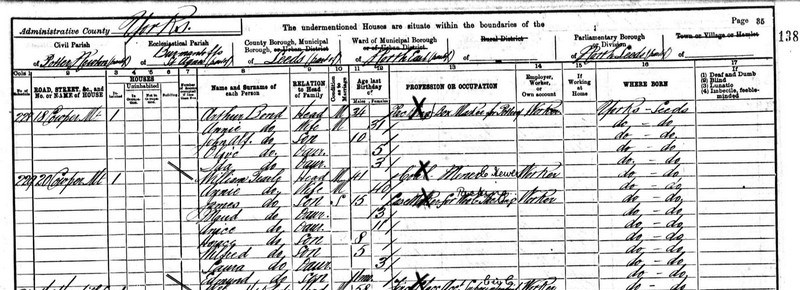

1881

Since Montague was born in 1874/5 he should have been in the 1881 census, and since he had mentioned a brother, Walter, then there should be a family containing a Montague and his brother Walter. There was no Montague Tearle, but there was a William Woollen born 1875 in Sheffield with an older brother Walter E Woollen. They are living with their parents, William J, 31, who was a silversmith born in Wath, Yorkshire and mother Lucy, aged 31, from Ince in Warwickshire. There are four Waths in Yorkshire, but we can safely say that William J Woollen was a Yorkshireman.

1891

William is 16 and he is a lithographer, Walter Edwin, the elder brother, is 19 and he is a warehouse assistant, while their father William James, now aged 41 has given up silversmithing and he has become a journalist.

1901

Walter Edwin is 29, a warehouse sales assistant, and he has married a girl from his home town of Sheffield called Alice Maud Kenyon. Alice’s father and sister are living with them. Walter’s own father William J, who has returned to silversmithing, and mother Lucy E are living in Albert Road, Sheffield. There is no sign of William Woollen 1875, nor of Montague Tearle. Was he in prison?

1911

We now find out which Wath William James Woollen comes from: Wath-on-Dearne in South Yorkshire. He is 60 years old and still a silversmith. Lucy Ellen is 60, they have been married 39 years and had two children, neither of whom has yet died.

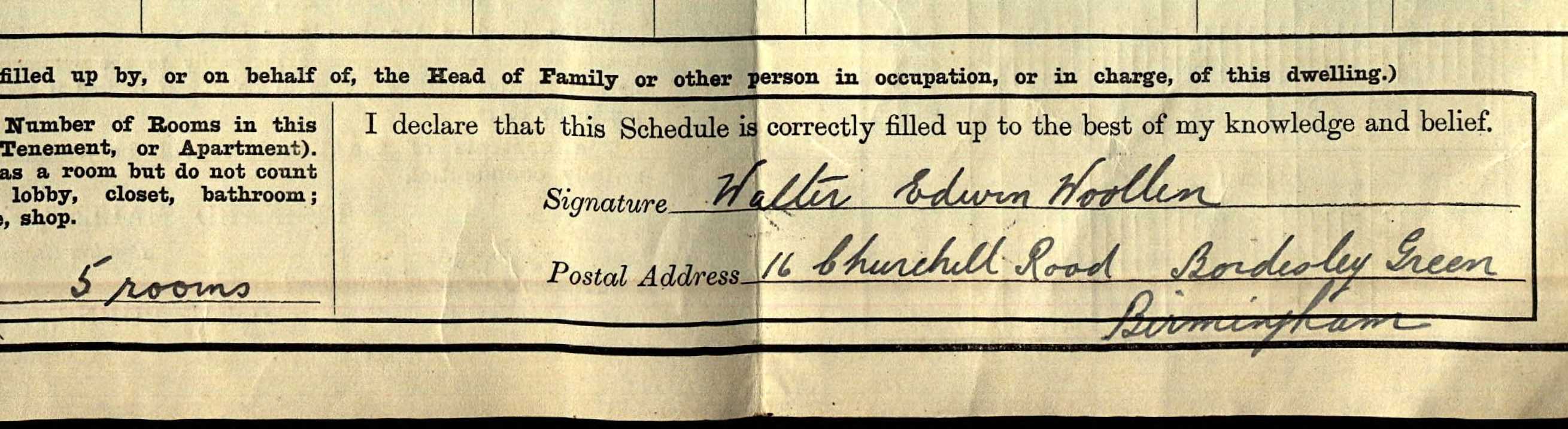

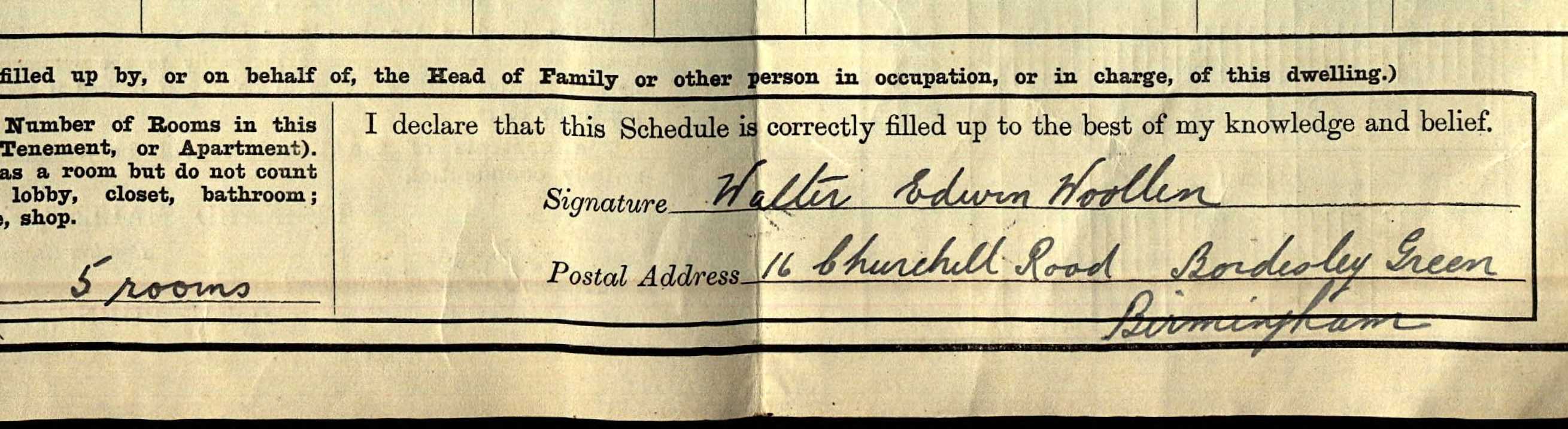

Walter Edwin, 39, is a clerk in a motor manufacturer’s factory in Birmingham. He is living with his wife, Maud and a boarder, who is a fellow clerk from work. More importantly, the 1911 census gives us the final, unimpeachable proof of who Montague really is. His brother Walter Tearle who lives at 16 Churchill Rd, Birmingham is actually his brother, Walter Edwin Woollen. Montague is unmasked – his real name is William Wollen, born 1875 in Sheffield, the son of a South Yorkshire silversmith. There is absolutely no sign of William Woollen 1875, nor of Montague Tearle, in this census. Was he in prison – again?

Not being in the censuses of 1901 and 1911 does not indicate that Montague was not working, nor was William Woollen completely buried as an identity. It is quite likely that Montague was either in prison, or he was being careful to stay away from the census enumerator.

We can go full circle now: we can join up William Woollen, the boy in the working-class neighbourhood of 1881, to Montague Tearle, the ne’er-do-well of the newspaper reports and the army recruit of 1915. In giving his next-of-kin as Walter of 16 Churchill Rd, Birmingham, Montague gave us one small fact amongst all the distractions, and that one fact told us who he really was.

1911 Walter Edwin Woollen 1872 of 16 Churchill Rd Birmingham