“Hello, Dad.”

“Genevieve!”

“I’m ringing on my mobile because I wanted you to hear this.” There was a pause.

“Burble, bobble, na, na, goo, da, la, la, la.” Another pause.

“You have a grandson, and his name is Liam.”

“He sounds absolutely gorgeous. How long ago?”

“A couple of hours.”

“So you are ringing me from hospital? Are you allowed a cellphone there?”

“I don’t know. If they don’t want me to use it, they’ll take it away, but I’ve done what I wanted with it, anyway. I rang you. We’ve called him Liam Tane de Vent.”

“Is it Irish? We wanted a name that would sound the same in any language. We go to so many places that we thought we’d see if we could find him a sort of universal name. Liam sounds the same in English as it does in Dutch, French, German, Spanish, Mandarin… see what I mean? We spent hours with a names book. Barry also wanted a New Zealand connection in his name because with de Vent he has a Dutch one, and he doesn’t want Liam to forget he’s also a Kiwi; that’s why we called him Tane, as in God of the Forest.” I could sense her smile on the phone. “It’s a very green name, too.”

I could still hear his gurgling baby sounds very clearly in the background. A happy baby and a deeply satisfied new mum.

“Well done, Joni. We are so proud of you.”

What new baby ever comes home fully fault-free? Once released

from the hospital, Joni became unwell and somehow this caused

strife with an overzealous visiting nurse. Barry’s mother, Leny,

was an excellent source of help and support, but she couldn’t be

there all the time and sometimes events and the emotions that go

with them swirled around Joni uncontrollably. Elaine had a chat

with both Joni and Leny and they agreed a girl needs her mother

from time to time. She spent a week with Joni, Barry and Liam

and when she returned she was ecstatic.

“What a beautiful baby! What a lovely little boy!”

Sheswallowed the tears that welled up in her throat. “

You know, that was one of the best times I have had with Genevieve

since she left home in the fifth form to go to Girls High.”

Babies do that.

Only once in your lifetime do you have a first grandchild. If we

had done nothing else all year except this, and our visits to

Amsterdam and their visit to see us in St Albans, we could have

counted this year as a full and rewarding one, but of course,

that’s not the way things work; those trips to Amsterdam were quite memorable for very different reasons. On our first trip to see Liam, we dovetailed very nicely with the visit to Amsterdam of our sister-in law, Kathy Pond, Elaine’s brother Gordon’s wife. She, too was delighted with the reception little Liam gave her. Joni tied on him his All Blacks bib and he charmed her with smiles and gurgles that she simply could not resist.

Leny and Cocky had very generously given us the keys to their house in Amsterdam while they spent the week in their summer house, and after we had worked out the route from their place to Westerkerk and thence on to Haarlemmerweg, as Genevieve’s building is called, we were able to walk it in about 20min.

“It’s good exercise,” said Elaine.

Mmm

“Have you been inside?” asked Joni? “You’re living nearby

at the moment. Westerkerk is a stately, beautiful place.”

“It’s beautiful from the outside, all right, and I have always

loved the sound of its bells. Those are the same bells that

Anne Frank wrote about in her diary. But I’ve never been

inside it.”

“It’s worth the visit. Rembrandt’s there.” Genevieve knows

what makes me tick. “I don’t think he’s actually buried in the

church, it’s not the Calvinist way, and besides he died a

poverty-stricken, unknown old man, buried out of town in a

pauper’s grave. Westerkerk was his church, though, and once

the city fathers saw that he was one of their most famous sons, they put up the memorial in the church for him. You’ll have no problem finding it because the inside is very plain and unornamented and the Rembrandt memorial is quite flamboyant.”

We also took an afternoon stroll with Barry, Joni and Liam to see Jenny and Han’s summerhouse. This isn’t exactly it, but the picture shows the style of construction and the quite luxurious setting in

the middle of a bush-clad park to the south of the 250-acre Westerpark. The buildings are not allowed to be heated, nor to be occupied out of the summer season, but they are none-the-less the

genuine beach bach that New Zealanders would instantly recognise, when they remember the days of packing-case cottages on sandy spits and rocky outcrops overlooking the sea.

We had visitors, too. Jim and Dos Mark came to see us from their farm near Te Awamutu. We picked them up from St Albans City railway station and we spent a very nice afternoon in the

sunshine walking around the market, the cathedral and Verulamium Park, as well as the obligatory visit to the Fighting Cocks pub. A former colleague of Elaine’s came and stayed with us. Judy

Dixon and a friend from Federated Farmers, Trudy, stayed for a couple of days with Iris and we took them to the Wicked Lady pub for dinner.

Kaye and Merv Thorburn from Te Awamutu brought

us news of their new life as retired farmers. Nice work when you can get it. They have built a new house overlooking the valley they have farmed for so many years and we sat at our table overlooking our little park and tried to find reasons why each of us had lost their son. There is no reason, and there is no cure for the loss. Each of us felt that somehow there might have been something we could have done to prevent the accident that overwhelmed our boys, but the awful

sense of not being there to help when we were needed the most, the knowledge that we knew nothing until hours after the event, and the deepest sense of what might have been, if our boys were still with us, hurts as intensely now as at any time in the past. Elaine and I had lit a remembrance candle in Westerkerk, and for a moment, as we reflected on the things our Jase had done and the people whose lives he had brightened, we felt that perhaps his life had not been in vain, but we wished even more that we were still able to share these adventures with him.

Hamilton Boys contacted us to tell us who the recipient of this years Jason Tearle Memorial Trophy was, and while we knew that he was not forgotten, we still wish, more and more forlornly, that we still

had him. Friends always bring us both smiles and tears.

“Elaine, would you like to meet us in Portimao? Marilyn and I are going to stay in my timeshare and there is plenty for room for you and Ewart. The hotel overlooks the beach and there is even a

swimming pool.”

“Porti-what?”

“It’s on the Algarve. You’ll love it at this time of year.”

“Portugal would be wonderful!”

Frances Rawlings used to be the editor of the Waitomo News, which she took over from her father and then sold when she retired. She and Elaine had been friends since the early days of Elaine’s working for the Waitomo Development Agency in Te Kuiti. She is a passionate, intelligent, earthy woman who wears autumn colours with a panache born of red hair, an infectious laugh and

sparkling blue eyes. Portimao was a good choice. The English like the

weather in the Algarve, and they throw off their inhibitions with their clothes in the clear air and bright sunshine.

The Rock is what the area around Portimao is famous for, and this

picture shows it at quite a low tide, with the surf lifeguard and beach

concessions to your right and the café and sunbathing areas behind us and to our left. It’s a beautiful, long beach and one to be admired and treasured. Fortunately, the English aren’t the only ones who go there, so the Manchester fish wives with their rowdy children and boozy husbands, their loud voices and their habit of flashing their red knickers while they dance on the tables, have to share it all with the Irish, who built this resort and lost an incredible lot of money when the bubble burst and they couldn’t afford to finish the projects they had started. Deep holes in the red clay fight with half-finished high-rises for whatever money is left to continue the development.

The holiday makers – Frances, Marilyn, Elaine and I – watch on, enjoy the sunshine and stroll in the gentle waves that lap the length of the end-on-end beaches of Praia do Vao and Praia de Rocha. Nice place.

The thing about summer in England is that it contrasts so vividly with the winter that precedes it – or follows it, depending on your personal preference. The St Albans Snow Day definitely proceeded this summer. No hint of how heavily it would snow could be discerned at Christmas, which was really quite mild. There were

a few frosts in January, but nothing out of the ordinary. However in the first week of February it snowed, then paused, then snowed, took a breather for a day and then fairly chucked it down all night.

On 3 Feb when the sun came out, there was an incredible sight of a smooth blanket of pure white snow glistening on the fields, with deep black pencil marks for roads and lines of green-brown smudges where the hedgerows followed the fence lines.

I walked over most of Jersey Farm, Sandridge and Smallford, including a very nice stroll through the grounds of Oaklands College, which is the local farming training institute. Two sights stand out.

One is the Jersey Farm Woodland Park pond which was frozen over and carried the starburst of a snowball that someone had thrown at the ice, trying to break the surface. The second was watching a young snowboarder trying to avoid almost certain injury by throwing himself off his board before he hit the fence at the bottom of his run. You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din.

The trains stopped running, the buses were parked and did not even leave their garages and Elaine went to and from the school each morning to post “Sorry we are closed” messages for parents hopeful the school would open and take their fractious children away. Our little Hyundai could easily negotiate the drift-covered, slippery roads because it’s an automatic and will go as slowly and delicately as conditions dictate. The 4x4s had no hope. Their tyres were too slick, they carried no chains, and the power they hit the road with left their wheels spinning helplessly as they slid gently and inevitably into the ditch. Elaine sailed serenely past in her cheap little import and carried on with her business. The mayor of London, Boris Johnson, was asked about the snow conditions that had brought the mighty heart of London to a standstill. Was this just another case of the wrong kind of snow? “No, no,” he said. “It was the right kind of snow, just the wrong kind of quantity.”

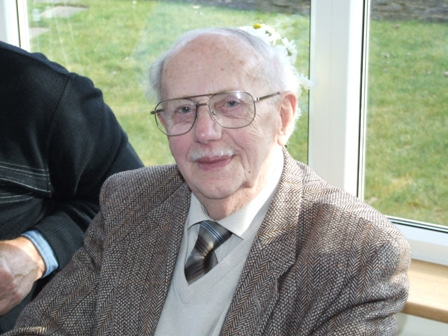

We also lost two of our family’s best friends this year. You may remember Roland Adams. He was a nephew of my paternal

grandmother, Sadie. He was the very first person from England to visit my father, since Len Adams had been to see Sadie in the 1920s. He had rung me from Auckland and had travelled by bus to the Waitomo, where he met Elaine, who arranged to be with him while he went on a tour of the Waitomo Caves. Later in his holiday, he left the bus for a few days and we took him to Hahei to see Dad.

Roland was hugely impressed with the beautiful coastline and the fabulous little bay that lay almost in Dad’s front yard. He ascended the two flights of steps that led to the door and he and Dad met for the first time in their lives. It was very emotional, partly because of the memories that swept over Dad at meeting one of his family from the Old Country, and partly because it was Roland who had bought Dad’s small lathe for him and sent it out to him all the way from England, when they were both about 15yrs. It was just a bed and a head and a self-centring three-jaw chuck, and over the years Dad had made all its tools and even its screw-cutting attachment.

He had bought a four-jaw chuck for it at an early stage, but the rest he made. With the lathe he had made countless small motors and working steam engines. His enduring legacy will be a 3ft model of an Irish lake boat that he and my brother Graeme built and into which he fitted the most intricately finished and beautifully scaled steam engine I have ever seen. When Elaine and I visited Henley-on-Thames we saw the original. We gasped. The model, even down to the dolls that fitted inside it, was perfect. In sending the lathe, Roland had not only indulged my father’s deepest passion, he had also unwittingly laid the foundation stone for the work of a lifetime.

The second death in the family was very close to us personally and emotionally. Jennie Pugh was a darling, a sweetheart and Elaine’s best friend.

She had been to see Jennie almost every month since she had been in England, and she had been a confidante and an advisor. This picture is of Jennie and Elaine at her favourite restaurant, The Moat in Luton, in 2005. This is the Jennie I know and this is the Jennie I will remember. She told me all the old stories of Levi and Sarah, my great-grandparents, and the stories of their children and their children’s children. It was Jennie who had given the walnuts from her own tree that Sheila, Thelma and Clarice had planted on our Otorohanga farm in memory of Jason.

That tree had been planted from a walnut that Jennie’s cousin and husband Ernest Pugh had brought from Levi’s house in Wing. And the walnut that grew on the tree in Levi’s yard had come from the house of his mother, Mary Tearle nee Andrews, in Stanbridge. The two walnut trees in Whawharua carry the memories of my great-great-grandmother.

Jennie’s death will forever hurt us because it was long, it was painful and it was dreadful. It started with a diagnosis for diverticulitis, which three years later turned out to be a tumour. The doctor all

that time insisted that her pains were imaginary and her appointments to see him were unnecessary and time-wasting. He thought she was just a silly old woman. She was finally invalided to a care home when she couldn’t look after herself and within days she was drugged beyond recognition.

She had entered as a cancer patient and the heroin they gave her (there is a fancy name for it) was for the pain, but it made her almost unrecognisable. The Macmillan Nurses never appeared. When I

asked would they visit, the manager said they weren’t needed because Jennie was under the care of a District Nurse, and the home would call her when they thought it was necessary. We visited

Jennie every week, and we were heartbroken at her slowly deteriorating condition. Eventually she simply gave up. The drunken-headed incapacity she felt, the helplessness, the base and deprived living conditions, the smell, the cramped room she was never allowed to leave unless she was being carried to dinner, the bullying night nurse, all this finally overcame her and she gave her body one last command which it could not disobey; no food, no water, I am going to die. I want to see Ernest.

She turned her face to the wall for weeks. There was no sign of our Jennie in the little curled-up bundle of pyjamas in the hospital-loaned adjustable cot, just her body obeying her last command. It

was truly awful.

She left me one last legacy. When Levi’s sister, Elizabeth, married and moved to Huddersfield, everyone in the family called him Uncle Bedford, and when he died, Levi took the train all the way to his funeral in Long Eaton, Derbyshire. When Levi returned, he was carrying Uncle Bedford’s glass cane, and that cane had been standing against the wall in Jennie’s house since Levi died. A

few weeks ago, Jennie’s son, Norman drove from Chelmsford and presented me with the glass cane. It’s clearly old, it’s a pale green and it must be very brittle. I have mounted it on solid timbers in

the loft, and there it will stay until I have better plans for it. It’s not just a glass stick; it’s not even a Cane of Remembrance – it has its own life and its own story and it carries with it a raft of associations. It’s a treasure.

I must also record our deepest appreciation of a gift from Margaret Brookfield of Perth, Australia, of a quite magnificent hamper of Duchy Originals organic produce from Harrods of London. Margaret is David Palmer’s sister and Jennie & Joyce’s niece.

Joyce Palmer’s 90th birthday gave us an opportunity to explore part of England where we had little local knowledge – Norfolk. Interestingly, there were Tearle histories in Norfolk and on the Suffolk border. One of our ancestors had moved to Sandridge in the 1780s and had his children here until the turn of the century. Two of his sons became vicars, Frederick in Gazeley, Suffolk, and Edwin in Stockton, Norfolk. In both of these churches there is a stained glass window in memory of these men. Also, Elaine found out that there was family of her own in Norfolk, and we wanted to make sure we met Norah Lowe and her family in Stalham, and Elaine wanted to see her friend and ex-colleague Mandy, who owned a boat on the Norfolk Broads.

Joyce’s party was taking place at the home of her nephew David

Palmer and his wife, Yana. We had met previously at The Halfway pub in Luton for Jennie’s 90th. Joyce looks a little the worse for an adventure she had when she fell, but she was unbroken and looking forward to the party. David had driven all the way to Balham to pick Joyce up and we volunteered to return her so he didn’t have to make that long return trip twice, through busy, twisting London streets. David’s house is the former brewing house in Pulham St Mary and it’s part of a much larger conversion of the entire brewery into a hub

of flats and cottages.

Opposite, they are repairing the roof on the old church. Yana’s mother and stepfather arrived, followed by some village couples. Joyce loved her party. “I didn’t have a 21st birthday party,” she explained. “My elder sister, Edith, died and Mother and Daddy couldn’t find it within them to celebrate with me, so nothing happened.” She looked into her glass and then round the people gathered in David’s living room. “This is the best party I have ever had. The salmon was wonderful, and I must say it’s the first time I have ever drunk champagne.”

The following day, Elaine and I drove to Stalham with Joyce to visit Norah Lowe, Joyce’s cousin. Norah’s children were gathered in her tiny living room, as was Lacey, her darling great-grandchild. She busied herself bringing biscuits and pouring tea, and when she wasn’t serving real plates she served pretend ones on the seats to little invisible people, all of whom had names.

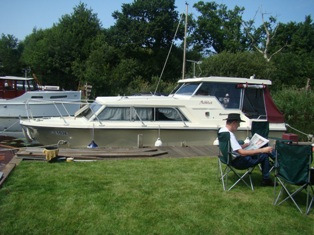

“Mandy, are you on the boat tomorrow?” Elaine asked on the phone that night.

“Yes, but we are not going anywhere, so you are welcome to visit us.”

Mandy knew Elaine very well. She gave her complicated instructions on how to get there, including something about some painted hatching in the middle of the road.

“Paint hatching?” I asked as we drove through the villages and towns of Norfolk to get to the Broads.

“Do you mean painted chickens?”

“Oh, just drive.”

“What’s wrong with the boat?” she asked, when we arrived and had settled down to a cup of tea alongside the barbeque.

“Nothing that I know of, is there, Colin?” said Mandy blankly. “Can you see something?”

Elaine had another go. “I mean, why doesn’t the boat go anywhere? Doesn’t the motor work?”

“The motor is fine, it keeps us warm sometimes. It’s quite useful for all sorts of things.” She stopped. Elaine waited. “We can cast off and go for a ride, but we can’t actually go anywhere.” It was Elaine’s turn to look blank.

“I’ll show you.” She skipped past a small dinghy that Colin was working on and walked briskly to the end of the canal. “Do you see that bridge down there on the right? Our boat’s too tall to go under it, and too expensive to lift over it. The canal we are on is a dead end behind us and there is another bridge like that one about a mile to the left of our canal. We can go boating all right, but we can’t go

far.”

“So your boat is rather like a floating caravan on a fixed berth?”

“Precisely.”

“Why did you buy it if you can’t go boating?”

“Because the Broads is a unique place. A beautiful place. You can only do 5mph, so you don’t need a large boat unless you need the room for sleeping accommodation. See the dinghy that Colin is working on? We run about in that and we sleep on the boat.”

They took us for a short ride in the dinghy and we passed this quite magnificent, if a little fading, boat house. Where else on earth would you find a boat house with pillared porch? Classical palace from the front, bach at the back.

“What about Wales?” I said once we were back home.

“Yes? What about Wales?”

“Would you like to go to Cardigan Bay? Lie in the sun, walk on the rocks, watch the yachts sail by? Remember Phil Thomas from Sainsbury’s? We used to put the nose bags on and go for lunch in the café. We can go there for a few days. He’s given me directions – go straight through Swansea, stay on the M4 until it disappears and take the road to Llandysul. We’ll drop off in Cardiff for a few moments to see James at St Mary’s Whitchurch.” In order to go to Wales you have to cross the Severn and it’s not just any old river, neither is the Severn Bridge just any old bridge. It’s a toll bridge to start with and it is simply huge. You can see it for miles before you get anywhere near it, and when you are on it, the towers holding the suspension wires soar into the air above you. The tides below you run at eight knots and raise the water level up to 30ft between low tide and high tide.

The incoming tide passes the outgoing tide, and there is a boilingshere plane between them. Here is the reason we called in at St Mary’s Whitchurch. James was actually a Preston man who joined the Welch Regiment in WW1 because he was living and working in Wales. He died after the war ended, having survived it all the way through. He still has family living in Cardiff. At some time in the late afternoon we finally reached Llandysul, having driven about nine hours to get there.

True, the views were sometimes beautiful, but it was a shaggy dog who got out of the car and asked where Phil Thomas lived. It had started to drizzle a light, soggy rain and in the dim light I stopped an

elderly man walking briskly down the narrow footpath past the whitewashed houses and coloured doors.

“Who?”

“Phil Thomas. He lives on this road, but I’m not sure where.”

“Oooh, I know several Thomases in this town, but I don’t know any Thomas on this road, and no Phil anywhere in town. Ask at the pub over there, they might know, and they might let you use the phone to ask Phil where he lives.” I walked towards the tiny island of light across the road and passed into the public bar. “Phil Thomas? I know everyone in this town,” said the bar man, who I think was also the owner, “but I’ve never heard of Phil.” He looked around the other men in the bar, seeking confirmation. They all nodded. I took out my cellphone and flipped it open. It didn’t even say ROAMING.

“Do you mind if I use your phone? My cellphone has no coverage here.”

“Neither has anyone else’s,” said the barman cheerfully, handing me the phone. “If you are still here in the morning, you can climb the hill across the river and you’ll find a signal at the top.”

Phil gave me the final directions to his house and we pulled up gratefully alongside.

“Mate!” he said. “How good to see you!”

We climbed the steep, short steps to a small grassy yard, past a faded green shed and across some gravel to the door of the house. “Get back! Get Back!” yelled Phil. He pushed the door inward and two huge dogs bounded through the opening and crashed into our legs. “Don’t worry about them, they are just a little excited because they’ve been inside all day,” he said as the dogs wacked their tails against us and licked whatever of us they could reach. “They’re Rhodesian ridgebacks,” he said by way of explanation, as we edged through the opening and pushed our bags past the dogs into the hall, “but they are very good pets. The older one is a replacement for my first dog, who is in the living room, and the younger one is a stray we were given to look after.”

So there is another one to come. How do you get a replacement for a dog that isn’t dead?

He slowly turned the knob to open the living room door. “Sit!” he yelled. “Sit down!” We followed him into the living room, the ridgebacks diving through our legs to get there first. An elderly black

labrador dropped painfully from a huge red leather sofa pushed up against the wall and came to greet us.

Keren introduced herself as she pushed the skipping dogs apart. She was a short, slim, young woman with shoulder-length dark hair and a black ruffled blouse. Good looking, too; she was just back from working in the local Buddhist temple where she told us she worked as a volunteer several days a week. This was the temple that made British news headlines because their sacred cow had developed TB and had to be destroyed. No reprieve. She made us a beautiful dinner of baked spuds and slices of beef and then gave us the cook’s tour of the three-storeyed house. It was called Arwel and it was only a few doors from the pub I had visited. I digested this slowly while I unpacked the suitcases in the little loft bedroom. Painted white, with a brass bed, high pointed ceiling and a skylight window, the room was cosy and inviting. Huge oak beams supported a tongue and groove planked ceiling. Scaffolding outside told a tale of ongoing renewal.

In the morning I decided I’d tackle to issue of the stranger in Llandysul head on. “Prengwyn is just over that hill, isn’t it?” I said at breakfast. “You were born and brought up there. I suppose it would be 5 miles by road? Two miles as the crow flies? It just seems so odd that they don’t know you, when you live a few doors from them here, and only a few miles away from them all your life.” Phil took me outside and pointed to the hill across the river.

“If you climb the hill you can see most of Wales,” he said. “It takes about two and half hours to get there, half that to get down. When you get there you’d be able to use your mobile. The only trouble is, you have to walk the long way round because the short way across the river is by bridge, and it’s privately owned. Of course, you could join the Angling Club for £1000 a year, and take the bridge route or …” He paused. “You’d be unlikely to get there and back without a rain shower, too, on any day.”

He hitched up his green khaki trousers, tucked in his cotton shirt and smoothed out his old green jersey. His long hair and light stubble framed a face of fortitude and yet great good humour. “They call us The English,” he said slowly, uncomfortably. “I have lived here all my life except for some time in an English school, but I don’t speak Welsh natively. Anyone they view as a stranger is always called The English, no matter what nationality they really are.”

Elaine joined us and Phil whistled up the dogs. “I’ll take the dogs for a walk while I show you around,” he said. We walked down the hill and along a path that followed the river. A small weir chuckled on a sweeping bend and dark, peat-stained water splashed and sparkled in the sunshine as it danced over the weir and swirled its way off beh

ind us. “So you need to live in your valley all your life?” I asked.

“More than that, you need to have lived in your village and married a fellow villager. Your father and mother would have lived there and probably their parents as well. And you need to speak Welsh

as an infant. Anything else and you just don’t belong there.”

“I know how that works,” I said with some feeling.

“For ten years we lived in a village of about 60 houses, in the King Country, called Piopio. Everyone was related to everyone else and the Outsiders, who were related to no-one, were usually the teachers and the policeman. Strangely enough, from time to time, you would hear the villagers slag each other off and call one of them an Outsider. Everyone belonged and yet they didn’t belong. Sometimes they’d refer to themselves as not feeling that they belonged either. It’s tribal, this thing of villages. You are both important and yet nothing, you belong and yet for one reason

or another you don’t belong. Village life can be supportive, but

mostly it’s destructive, and the people they take most delight in

destroying is each other.”

“That reminds me,” said Elaine. “As we came into your road

there was a sign that said TOWN. I thought this was a village.”

“Do you see the church over there? It’s a big one, so this is a

town,” said Phil. “We are as good as Milton Keynes, which has

about 300,000 people in it, because we are a town, and so are

they. And we have about 300 people.” He grinned. “The

British have a way of elevating and levelling at the same time.”

We had walked some way down the road and Phil snapped

open a wooden contraption that looked like a stock gate,

whereby the gate opened only wide enough for one person to

walk through at a time as the gate swung in the V of two short

wooden fences. “It’s called a kissing gate,” he explained. “The

gate kisses, not you.”

We walked in cool, dappled gloom along a bush walk that rose quickly upwards while we looked for mushrooms and orchids and tried some small, bitter, black berries attached to miniature shrubs barely six inches high. “Do you see the ridge on the downhill side of this path?” He pointed to the trees growing amongst an embankment that followed our path. “It’s Iron Age.” I did a quick calculation. The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age, and that finished more or less when the Romans arrived, about 2000 years ago. “You mean somewhere between 2000 and 2800 years old?” I surmised. “Not less than 2500 years,” he said. “Our first settlers arrived in the 16th Century, at the earliest, so this has got a bit of

age on that.” “Ours started arriving as the glaciers retreated, 10,000 years ago,” he said, shortly. His ancestors had been here for all that time, and he still didn’t belong.

We took the coastal route for the rest of our holiday in Wales, determined to see as much of the Cardigan Coast as we could. There are two things that stand out about a summer holiday in Wales; it’s cold, and it rains nearly every day. Here is the beach at Llangrannog on a lovely, sunny Welsh summer day. The craggy coastline is bitten into by sandy little nooks like this where the locals and the English

enjoy the lifestyle. Behind me is the café on a rocky knoll and in front of me people are swimming in their wetsuits and enjoying the sun in their anoraks. It’s going to take a long time to get a tan. When we left, Phil said, “That was the finest spell of weather we’ve had all summer. Three days of sun is a miracle.” “A gift from the sunny Waikato,” said Elaine with a flourish.

The second thing we remarked on was a genuine surprise, no less because it was directly related to our own city of St Albans. This is the town of New Quay, sometimes spelt Newquay, even on the road signs. You can see that it’s still a commercial fishing town, even though it’s on pretty hard times. The Cardigan Coast faces Ireland and the Irish Sea is as cold, stormy and unforgiving as the Tasman. We walked along the beach, warming our toes in the dry sand, watching the locals digging moats around their sand castles and pestering their mothers for ice creams. Large grey seagulls screamed and dived overhead and a small group of teenagers was attending a coaching session on surf rescue being run by an enthusiastic young man in a black and yellow wetsuit who was encouraging them to jump into the water from the surf ski. To our left another group, but much older, were working on an orange inflatable zephyr. We approached the zephyr and took a few pictures of the scene as the men worked. An older man, greying and distinguished in a blue blazer with RNLI and a Commodore badge on it wandered over to us.

“What broke?” I asked, after we had introduced ourselves.

“The inflatable part of the boat has some patches of perished rubber, so we are repairing that and we’ve taken the opportunity while the boat is out of the water to make some improvements and adjustments to the motor.”

We watched the team with interest, and Elaine said,

“Where did the boat come from?”

“Do you mean how did we pay for it?” asked the Commodore. “By public subscription, private bequests and a hell of a lot of fundraising.”

I looked at the impressive club shed and noted the launch inside, he saw my glance. “That, too,” he said with feeling. “The one before it was called the St Albans because all the money for it was raised by a group in that lovely city.” He swung his arm in a wide arc encompassing all the view, “We patrol everything on the sea between here and Ireland. We can be called out at any time of the day and night to save someone’s life, and every single one of us is a volunteer. The only paid man in the entire club is the engineer who is working on the motor of this zephyr. That’s a full-time, paid job.

Of course, he’s also responsible for all the equipment on the Lifeboat as well as making sure the tractor works every time it’s needed.” He had seen a signal from someone and he readied himself to leave.

“There are six hundred such clubs in Britain and every one of them survives only because of donations and volunteers.” A proud man. A good man. We had time for a wedding too, this time it was in the Cotswolds. Last Christmas our young neighbours, Samantha and Mark, had invited us to their wedding and they were talking to us about the arrangements. They had hired a water-mill in the hills and

would have their ceremony in a walled garden which had a covered walkway round it. If it rained, there would still be a viable ceremony, but if it was sunny, the view would be quite spectacular. This is the venue on a quite beautiful Cotswolds summer day.

It was marred slightly by a screech of tyres and the loud bang of two vehicles coming together, on the other side of the hedge behind which I had parked the car. When I arrived at the scene everything was calm enough; an older woman was being eased out of the front car which had been tail-ended by a huge 4×4. I took off my black suit jacket and stood in the middle of the road in my white shirt directing the traffic through the one-lane gap between the cars and the other side of the road. I didn’t have any authority to do so, of course, and if someone had taken it upon themselves simply to charge the gap, I could have done nothing about it. However, no-one did and everyone I waved down and asked to stop while cars drove past, did so and waited patiently for their turn. After about 20min, a police car screamed up with its blue lights flashing and a young cop jumped onto the road and waved me out of the way. Job done. No-one dead.

After that, the wedding was a piece of cake. We met all the friends

who Mark and Sam had talked about and whose names I was familiar with, but whom I had never met. Nice people, too. It was simply a glorious day; and the accommodation in the mill was superb. In this photo, Mark is examining the garter that Sam has insisted he look for. You can see the low stone wall behind which is a beautiful little pool and the walled garden with coloured lights, a small fountain and a brass statue of a semi-clothed girl who must be freezing by now with all that cold water constantly flowing over her. I made up a CD of the day’s photos and mailed copies of it to Sam, her parents

and a few of her friends.

You will remember Thelma Shepherd, Dad’s cousin, who was our first contact in England way back in the middle 80s when she answered an advertisement that Barbara Tearle had placed in a

local newspaper, enquiring about relatives of Levi Tearle of Wing. Thelma lived in Wing and she made the monumental voyage to New Zealand to see us in the same year Jason was killed. Her son, Martin, lives in Warwick and works as a designer for Land Rover. He sent us a card – would we like to come to his 40th birthday celebrations in

Leighton Buzzard, with a trip on the narrow gauge steam train? Of course we would. This is the train as it pulled into the Leighton Buzzard station. I suppose the gauge would be about a foot, and the original train hauled sand. It looks awkwardly tall for such a skinny footprint, but if you put people into such a machine, it needs to be tall enough to accommodate them. It wouldn’t look so gangly if it

was hauling the old sand wagons.

“It hauled sand from near Heath and Reach to Dunstable,” said Martin as we stood on the platform and admired the train we knew had been an obsession of his since his boyhood. He still travels to

Leighton Buzzard from Warwick almost every month – to keep his steam certificate current, he insists. “It’s very pure sand and it comes in a range of colours, so it has lots of uses, especially in construction. After the War, the local farmers who were mining the sand were told that their drays were ruining the road, so they had to pay for repairs.

They weren’t keen to accept the cost of maintaining public roads, so they extended this narrow gauge railway to Leighton Buzzard. The

sand could then be offloaded onto boats for cartage down the Grand Union Canal to London.”

“So this railway dates to just after WW1?” I asked.

“1919 to be exact,” he said.

We climbed aboard for the return journey once the engine had been turned, and the train let off lots of steam and loud toots of its whistle. The sharp, acrid smell of coal smoke made me wonder what

the owners of the trim tidy houses that lined its route thought of a coal burning locomotive on their back doorsteps. Perhaps they weren’t allowed to complain; after all, the loco was clearly there

before they built along the course. The train stopped at the one road crossing on its journey, not far from Sheila Leng’s house on Hockliffe Rd. Tall beech trees lined the course and green dappled light filtered into the train. Two men jumped off the train and ran either side of it out onto the road. One car going to Leighton Buzzard from the left of the train, stopped to watch; another from the right, heading to the A5, charged the crossing to avoid being held up. This is the crossing where I had often sat and watched the train gently rock itself across the road. Martin climbed down from the train as soon as it stopped at the terminus and had a chat with the engineer. Two experienced, dedicated men, giving of their lives for the survival of their history and the education of their children.

The smell of the coal smoke had made me remember my time near the railways: I lived for 6 weeks in the now-burned down Empire Hotel in Frankton near Hamilton, NZ. It was interesting…. The cook was a great guy – huge, bald, loud, dressed in a white singlet, canvas trousers and black boots, sweating all the time. He cooked a swathe of bacon, and a bucket of sausages, in a yard-wide cast iron frying pan over a red-hot coal range while the eggs gently boiled in little cups alongside a smaller pan of frying onions. The under-cook passed him hot plates from the oven and he slapped some bacon, a

couple of sausages, onions and an egg on each plate and then whacked it down on the counter, swinging it along the shiny surface until the man at the head of the breakfast queue swept it up before it hit the floor.

You could hear each man take the plate and swear at how hot it was as he carried it back to his table. They seemed to know a lot about the ancestry of the cook. My bedroom was on the second floor and overlooked the railway shunting yards. The drivers and engineers

yelled orders and banged trains together all night long, but no more energetically than at eight o’clock in the morning when everyone in Frankton had to cross the railway line to go to work in Hamilton. At that hour of the day here was always a train (or two – it was a dual line between the station and the shunting yards) across the only crossing on the only road to Hamilton.

The hotel – more a boarding house, really in the way it was run, was a wooden structure clad in weatherboard. It was quite a handsome turn of the century building painted green and white with a large gold sign. Even in the nineteen sixties when I was at university, it had seen its best days. The green was faded, the white was dirty and the sign was cracked and had bits missing. The stairs creaked, the roof leaked and the manager put his head to every door in the hotel to assure himself there were no girls in the hotel after nine PM. In fact, women were not allowed in the hotel in the day-time let alone stay overnight. The hotel had A Reputation and the manager was determined to stamp it out.

I suspect (as did the local press) that a disaffected lothario burnt it down when his girlfriend was discovered under his bed. The tragedy was that he killed six in the attempt to extract his revenge on the hotel, and he is still in prison for the offence.

I suppose that sooner or later I should tell you about my job situation. It didn’t start very well, with last year ending in unemployment. At least the flat was paid off, so we didn’t have the

worry of having to find £600-odd per month for rent, or the mortgage, but being out of work is not a good feeling. I had some work, with the Our St Albans magazine asking me for my photos, but

while it was good to be wanted, and my photos appearing on the cover of the magazine, there was no money in it. I had to register as a Jobseeker and that is not a nice experience, nor is the constant trekking into town every week, to prove to them that I was still looking. No money came from them, either. I was paying to see them, but they weren’t paying me the promised £62/wk, so I was on a definite loser. I applied for a job with an IT company in Harlow, it wouldn’t be easy getting there from here, but with a bit of careful driving it should be manageable. I had a phone interview with the IT manager, to make sure I had some proper IT skills, and another one with the IT manager and his boss. When they said they would like to meet me, I was pretty pleased. First, though, they wanted me to take some on-line psychosomatic tests. Or perhaps psychometric, I don’t know. All I know is that there were tests of sentences where you were told one thing then asked what didn’t happen? Then there was a test where you had to say what the upside down word was. Then there was a test of four symbols which were inverses and mirrors of each other. Which was the upside down reverse? Then there was the rotated symbol; which one was rotated only three times? Something like that. I cannot, I never have been, able to reverse or mirror things in my head, I always have to make a model of it and rotate the model. The tests were 40 tests in 20 mins. I couldn’t finish them in time, except for the first one. I failed miserably. They rang me the next day

to say “No, thanks.” Even that was an improvement; no-one ever rings. Elaine introduced me to the IT tech who managed the computers and network in Sandridge School, and he organised a phone interview with David Wall, the owner and manager of IntermIT, which was the company that supplied these IT services to

schools. I registered as self-employed on 9 Feb 2009, which was the day I signed the agreement between me and IntermIT. It seemed a very slow start, but with some training on the peculiar networking technology they use here in Hertfordshire, and some shadowing of the local IT techies, I earned a couple of schools of my own, firstly just a few hours a week, then three days a week and now, in the New Year, I shall start at 10:00 on Tues and then work 8-hr days until 5pm on Fridays.

It’s quite a cool job. I fix dying PCs and I resurrect dead ones. I administer the school computer network and clean the overhead projectors. I install new PCs and run housekeeping jobs on the

entire network and its printers. To start with it was unutterably foreign; the network system was unique to a small company in Abingdon, Oxford, called RM, and it had been a long time since I had

been close to individual PCs, so I was no longer intimately familiar with Windows XP Professional.

These days, though, I see recurring problems and I very seldom have a day where anything is unusual. Some schools have me for a two hour stint per week, and others have a four-hour block. It depends on what they sign up for. I prefer the four-hour schools because there is always a harried dash between schools, so to have only one cross-town trip between two four-hour schools is a much nicer day than three such trips between two-hour schools.

It’s also very nice to walk into work and for people to say “Oh, Ewart! How nice to see you.” At Watton-at-Stone, they asked Elaine and I to come to their staff party, St Anthony’s School in Watford gave me Christmas dinner and the Ryde School gave us a bottle of mulled wine and a box of chocolates. We put those on the Christmas table.

The money from my Jobseekers Allowance arrived in the first week in December and I was pleased we weren’t absolutely desperate for it way back in January. Not that we would have got a cent at

home, anyway. When I was out of work for a short while before Waitomo Computers started, I called at the Te Kuiti job centre to enrol as unemployed and the lady said she wasn’t going to pay me anything. “You’ve got a house, haven’t you? You have to sell that first and when the money runs out, we’ll have another look at your situation then.”

So at least I am now gainfully employed, and I do like the work.

Strangely enough, the year has ended as it began. Snow; lots of it. Perhaps a little earlier than last year, or it’s possible that we’ll get another load come February. Whatever the case, this isactually our 10th Christmas in England, and our 10th Christmas in St Albans. I remember our first really well. We were so surprised we were still actually here, we hugged each other and danced in St Brelades place, while we listened to the local choir sing carols in the frost and the dark. They stood in a semi-circle in their red cloaks and white hats, holding fluttering candles that somehow stayed alight, while they sang like angels. It seemed really odd to be celebrating Christmas while being freezing cold, and the day had been pitch black since ½ past 4. Now, it’s how Christmas ought to be; that’s why there are logs on the fire – actually, that’s why there’s a fire at all. That’s also why there is a roast in the oven and baked vegetables to eat, Christmas pudding and fairy lights. It’s all part of Christmas in the dark and the cold. Christmas is a mid-winter celebration. From now on the nights get shorter and spring is coming.

I still had a problem with how to celebrate ten Christmases in England. I settled on Luton Hoo. We had been to see Four Weddings and a Funeral at the movies in Hamilton and we had see it twice more on TV, although not deliberately. All the action in the cars to and from the beautiful house with the portico, is on the driveway into Luton Hoo, although the evening scene of attempted seduction took place in a nearby hotel. Since the movie, the stately home has been bought by a small hotel chain and it has been turned into a very beautiful hotel, spa and conference centre. I’ll take Elainethere. A

chauffeur-driven car? I found one of those, too.

“Make sure it’s warm, because she won’t be wearing very much.”

“It’s a Mercedes, Sir, and it is not only warm, it has heated seats.”

Elaine bought herself an elegant cocktail dress and evening sandals from Debenhams. She went to Pure, the local beauty salon, and had her eyebrows shaped, a manicure and a facial. On the evening before she went, she also had a pedicure. In her dress and sandals, red fingernails and toenails and a new hairstyle, she looked sensational. I gave her a ruby necklace that I had been saving up for all year. Perfect.

The car arrived exactly on time at our flat and the driver eased the car out onto the road. “I’m a little worried about the snow,” he said as he accelerated up the hill. “These rear-engined German cars simply cannot hold the road in icy conditions. I’ll keep my eye out and if the weather worsens I may have to come and get you in a different vehicle.”

“All right,” I said, “but I want a posh one.” The driver grinned and turned up the climate control. Luton Hoo was as gorgeous as we had hoped. As we drove up the mile-long sweep of its approach, we could see its tall buildings outlined by concealed lights reflecting in the gloss of deep ridges of freshly fallen, glistening white snow. A doorman eased open the car door and Elaine gingerly stepped out onto the frosty tarmac. The portico overhung the steps but not far enough over the drive to allow a dry footfall. We helped her up the stairs and she practically melted into the warmth of the Luton Hoo entranceway. Tapestries hung on the walls and Italian marble faced all the corners and most of the niches.

“The marble cost more than the entire estate,” said our dinner waiter, while he led us to a sofa near a huge fire. “I’ll come and get you once your dinner order is complete.”

It was just a magic evening.

There is a short update to the story that began this letter – Joni, Barry and Liam are now in New Zealand and they have spent Christmas with Elaine’s mum, Alison Pond, in Hamilton. Liam is

her first great-grandchild, and she was simply ecstatic to see him, and to renew her deep and loving friendship with Genevieve. They will be in NZ for another couple of weeks, and we wish them all

the best.

I have to ask myself if it was all worth while. Did I do the right thing in dragging Elaine 12,000 miles around the globe to live near London? Was all of this a waste of time? Could we have done something better? You have to give Elaine a huge amount of credit for tidying up all our affairs at home before we left, for allowing herself to be wrenched away from the only home she had really wanted all her life – a beautiful house nestled into the hillside overlooking a lovely green valley.

She had to start everything all over again; retrain as a teacher and climb the ladder of promotion like any rookie. She had to prove to the English that she is as gifted a teacher for their children as she was for Kiwi kids. You can’t say that, you have to prove it. Year after year, her kids have simply adored her, she is showered in thanks at the end of every term and parents who initially found their children were forced to go to Sandridge by some invisible bureaucracy and truculently berated her for the future possible shortcomings of a stranger and a foreigner, found themselves admiring her and then thanking her for the opportunities she had given their children, which no teacher had ever offered before. But that’s not why she came here; she had already proved all that and she had hoped the Agency had put it all behind her.

She came here because I came. For that, I cannot thank her enough. I think that life in St Albans has been better than it ever was in New Zealand. We have had adventures in England, Europe and Africa that we could never have hoped for in New Zealand, and neither of us would have missed living so close to London. Our friends still come to see us, and those who can brave the ladder roost in the loft; we had Iris and Jill over for a most beautiful mid-week Christmas dinner that Elaine prepared and we had Christmas Day with friends in Cuffley. Our cup literally runneth over. Our one-roomed flat is not a house but it is most definitely a home.

May we both wish you the very best of a modern Merry Christmas and we do hope you find fulfilment and rewards in the New Year.

Lots of love

Ewart and Elaine.